Is monetarism making a comeback?

Read publication here or click here

Monetarists believe inflation is ‘always and everywhere’ a monetary phenomenon, driven by money supply growth only. As inflation runs rampant around the world, the monetarist school of thought has been making a comeback. During the last three decades, the link between inflation and money supply was found to be insignificant. Yet, money supply growth was one of the few leading indicators of post-pandemic inflation, especially since the start of the inflation surge. This shows that money supply growth is a less good predictor of inflation in well-anchored low-inflation regimes, while being a good predictor in high inflation environments. This has important implications for policy makers around the world and can provide us interesting information on the trajectory of inflation in different economies in the near future.

Introduction

“Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output”, the quote of Milton Friedman, the greatest standard bearer for monetarism, perfectly summarizes his school of thought. Monetarists see money supply growth, rather than supply chain disruptions, energy shocks or government spending, as the prime and ultimate driver of inflation. As monetarists believe central banks to be in control of the money supply, they thus see independent central banks as the only institution responsible for keeping inflation in check.

Monetarism on the rise

Monetarism gained traction in the 1970s, when inflation ran rampant across the world. From 1971 to 1980, inflation averaged 7.7%, 5.1% and 9.1% in the US, West-Germany and Japan respectively (see figure 1). The high and persistent inflationary pressure spurred central banks around the world to tighten monetary policy. Fed-chairman Paul Volcker e.g. raised the Fed Fund rate from 11% in August 1979 to a staggering 20% in March 1980. The rate rises had a shock effect on the US economy. Inflation declined from 14.6% in March 1980 to 3.6% three years later. The US monetary base, the supply of currency plus the portion of commercial bank reserves stored at the central bank, saw its growth rate decline from 11.3% end of 1979 to 4.5% two years later. Monetarists felt vindicated and became the dominant school of thought.

Japan and the Great Financial Crisis diminish monetarism’s stature

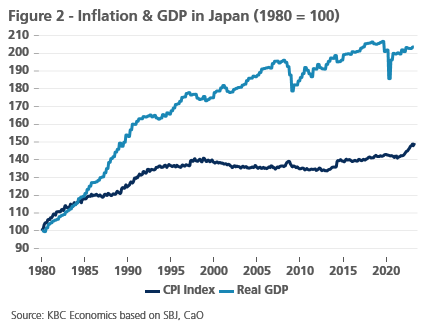

Yet monetarism’s status would soon diminish. First came a massive property bubble in Japan, which burst completely in 1991. This would be the start of a long of a period of anemic growth and very low inflation. From early 1992 till today, Japanese prices only increased by 12%, mainly caused by the recent increases in inflation (see figure 2). The Bank of Japan was unable to turn the tide. A total 5 percentage points rate cut from 1991 to 1995 and the resulting expansion in monetary base did little to bring inflation back to life. Government spending or artificial price increases seemed to be the main way to spur growth and/or inflation. This was most clearly illustrated when the government hiked the VAT rate by 2 percentage points to reduce the deficit. The move plunged Japan back into a recession. Keynesianism, the school of thought which focuses on government spending as the main driver of growth and inflation, regained traction.

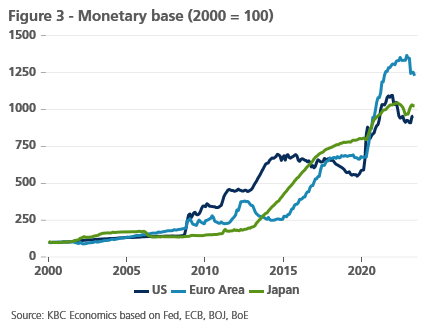

Monetarism’s star would further fade after the Financial Crisis in 2008. In its aftermath, many central banks across the world dropped their policy rates close to 0% and embarked on expansive quantitative easing programs, leading to rapid, unprecedented expansions in the monetary base (see figure 3). Nonetheless, this wasn’t enough to bring inflation back to target in any of the major Western economies. In the post Great Financial Crisis period (2009 – 2020), average yearly inflation rates remained well below central bank targets. They were at 1.6%, 1.2% and 0.3% in the US, the euro area and Japan, respectively.

Monetarism’s theoretical premises questioned

Monetarism’s theoretical foundations also became increasingly shaky. Monetarism’s holy formula is MV=PQ. PQ is nominal GDP as P stands for the price level, while Q stands for real GDP. M meanwhile stands for the broad Money Supply, also called M2. This metric includes not only the monetary base, but also overnight deposits, deposits with an agreed maturity of up to two years and deposits redeemable at notice of up to three months.1 Commercial banks thus contribute to money supply growth by extending loans, which provide extra money to borrowers (deposits), without taking away money from deposit holders. Bank lending thus creates a multiplier effect. The ratio of M2 to M0 (i.e. the monetary base) is called the money multiplier.

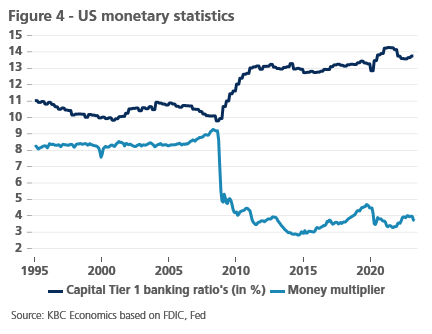

As monetarist see central banks as the entities in control of the money supply, they expect the money multiplier to remain relatively stable. However, the money multiplier became more volatile after the Financial Crisis. Strict regulation and market uncertainty then forced commercial banks to increase their reserves, which had a depressing impact on the money multiplier (see figure 4). This unpredictable decline as well as large shifts in and out of M2 money-components made it harder for central banks to control M2 growth and thus bring inflation close to its 2% target. This explains why the rapid expansions in monetary base (driven by quantitative easing programs) had such limited effect on M2 growth.

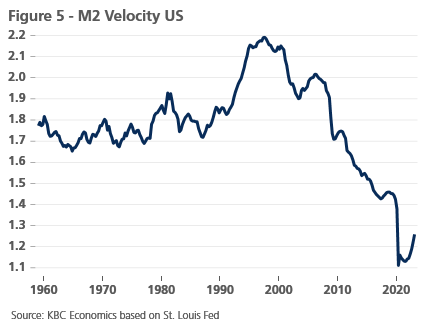

The last factor in the equation, V stands for the velocity of money, i.e. the rate at which money is exchanged in an economy (measured in number of times per year). Monetarists expect velocity to be relatively stable, which would make money supply the prime driver of inflation. Prior to the 1990s, money velocity was indeed stable (see figure 5). Yet in the early 1990s, money velocity rose rapidly. It later reversed gear and declined rapidly after the Great Financial Crisis.

Though the exact causes of these velocity shifts are still debated among economist, one of the main reasons seems to be the rise of shadow banking.2 Driven by financial deregulation and innovation, shadow banking activity grew faster than regular banking activity in the 1990s. Following the Great Financial Crisis and the subsequent regulatory tightening, shadow banking activity declined. As the ‘money’ created by the shadow banking sector is not incorporated in the M2 metric, money velocity became more volatile (e.g. less liquid money market funds) . Incorporating shadow banking activity in M2 would probably improve the stability of money velocity, though the data on this sector might be hard to come by. Regardless of what causes the instability in money velocity, M2 becomes a less accurate predictor of inflation because of it.

Post-Pandemic inflation revives monetarism

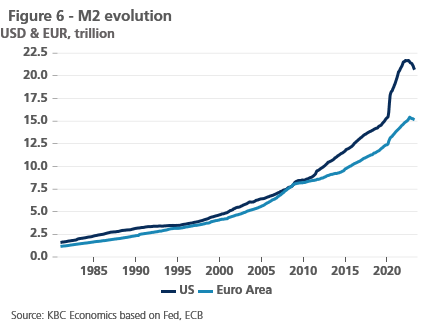

When Covid hit the globe, central banks followed the script of the Great Financial Crisis. They ramped up quantitative easing and drove the monetary base to record highs. Over the course of 2020, the Fed increased the monetary base by a staggering 1.78 trillion USD, a 52% increase, while the ECB increased the monetary base by 1.71 trillion EUR, an astonishing 54% increase. This time, however, banks were well capitalized and didn’t use the extra liquidity to build up their reserves. The money multiplier thus remained relatively stable and M2 grew well above trend, especially in the US (see figure 6).

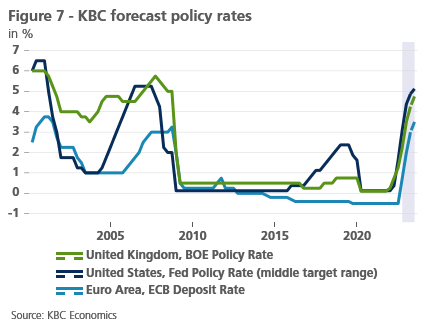

Many economists and policy makers initially ignored the excessive monetary build-up in 2020 and argued that inflation was well anchored and that deflation was more of a risk than high inflation. When the economy reopened, the initial inflationary surge was driven by supply chain issues, which drove energy and goods prices upwards. Many economists viewed this inflationary uptick as temporary and expected inflation to return back to 2% by the end of 2021. By December, however, US inflation hit 7.2% and core inflation reached 5.5%. In the euro area, headline inflation was 5% and core inflation 2.6%. Central banks then noticed that inflation was far from temporary. On the contrary, it was broadening and becoming more entrenched. They hence rapidly shifted gear and shrunk their balance sheet and tightened interest rates (see figure 7).

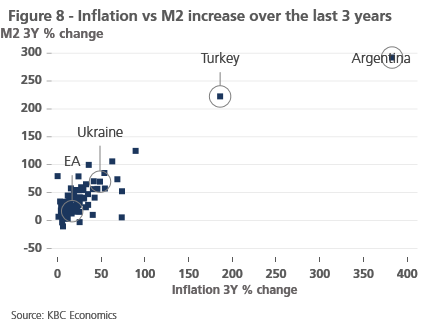

As inflation became sky-high, economists reopened their textbooks on monetarism. In a multitude of studies from the Bank of International Settlements, several economists argue that inflation behaves quite differently in a low versus high inflation regime . In low-inflation episodes, inflation mostly reflects the short-lived effects of largely uncorrelated sector-specific (relative) price changes. The correlation between inflation and M2 then becomes hard to find, as inflation reflects purely relative price changes . In the high-inflation regime, by contrast, sectoral price changes are highly correlated, as inflation is more sensitive to changes in general inflation drivers e.g. the exchange rate and wages. Prices are thus more tightly linked. The authors found that there is a statistically and economically significant positive correlation between excess money growth in 2020 and average inflation in 2021 and 2022. Our analysis indeed also finds a correlation of 0.88 between inflation and M2 growth in the last three years in a sample of 85 countries (see figure 8).

What’s next?

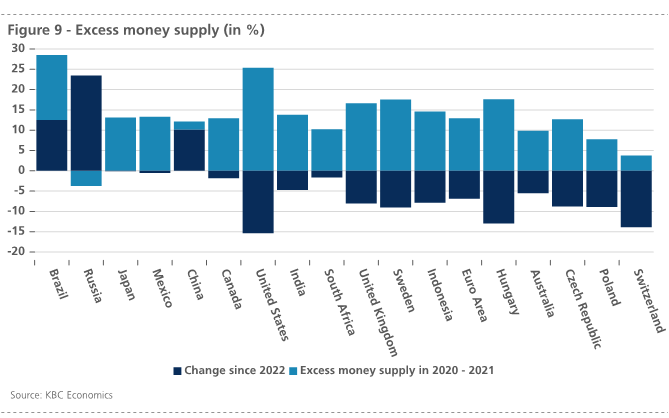

If, in the high-inflation regime, money supply growth is actually a good predictor of future inflation, the question remains what recent M2 growth can tell us about this crucial economic indicator. To answer this question, we divided M2 growth by nominal GDP growth, which could indicate how much excess money supply is still circulating in different economies (see figure 9). The figures show that the money supply is still too high in many economies and could be another reason for central bankers around the world to tighten monetary policy. In our sample of countries, nominal GDP growth outpaces money supply growth in only 2 out of 18 countries since 2020. In 7 out 18 economies, money supply growth outpaces nominal GDP growth by more than 10%. In the four largest economies, the US, China, the euro area and Japan, money supply growth outpaces nominal GDP growth by 10%, 12.1%, 6% and 13% respectively since 2020.4

The trajectory of excess money supply growth is also interesting. The US e.g. started to withdraw excess liquidity, as its M2 stock actually declined by 0.9% in 2022, while nominal GDP continued to grow. As the Fed’s monetary tightening policies continue in 2023, a further rapid elimination of excess money supply can be expected, putting downward pressure on inflation figures later on. In the euro area, excess money supply is being drained at a slower pace. That said, the euro area had less excess money supply to begin with. On the other side of the spectrum, Russia’s central bank rapidly increased its monetary base to counter the recessionary effect of international sanctions. That resulted in a large expansion in its M2 stock, which could fuel inflation in the coming years. China’s central bank also loosened its policy to counteract the effect of its zero-covid policy, leading an excess money supply build-up in 2022. It wouldn’t be surprising to see inflation rising somewhat there as well. Japan is also an interesting case. Its excess money supply is the largest of the major economies and is still rising as the Bank of Japan maintains its cap of 0.5% on 10Y government bond yields. Inflationary pressure could push the Bank of Japan to change course in the near future.

Conclusion

The current inflation uptick is leading to a more balanced view on monetarism. Keynesian economists were too quick to celebrate the demise of monetarism in the last three decades and ignored monetarist warnings of excess money supply build-up during the pandemic. That said, inflation is clearly not just a monetary phenomenon as the pre-covid era showed. This is especially the case in low-inflation regimes, where inflation is well anchored. When forecasting inflation, economists should include money supply growth in their forecasts along with supply shocks, government deficits, wage evolutions, sectoral changes, exchange rate fluctuation and so on. Doing so will lead to more accurate inflation forecasts and better monetary policy in the future, especially in a high-inflation environment.

1This definition applies to the euro area. There can be minor variation in the definition in other economies.

2"“Money Creation and the Shadow Banking System”, Adi Sunderam, 2012, Harvard Business School

3“Does money growth help explain the recent inflation surge?” Claudio Borio, Boris Hofmann and Egon Zakrajšek, 2023

4It is important to note that we assume money velocity to be constant in this analysis. That hasn’t been the case lately. In the US e.g., in the last 20 years, money velocity declined by about 2% per annum. It remains to be seen whether this trend persists.