“In the long run, we’re all dead.” But what now, ECB?

Due to the economic slowdown, the ECB is postponing the normalisation of its interest rate policy. At the same time, its inflation target remains out of reach, reflecting not only the slowdown, but also the continuing recovery in competitiveness in peripheral euro-area countries. As extremely low interest rates contribute little to the latter, it is difficult to see how exceptional measures would bring inflation substantially closer to the target. With exceptional measures, the ECB averted the risk of deflation, but by keeping interest rates extremely low now, it is undermining the profitability of lending. In this way, it is blocking an essential lever in the transmission of its policy. In the meantime, it is increasing the risks to financial stability. A reflection on the monetary policy strategy is needed. “In the long term, we are all dead,” Keynes wrote. But what now, ECB?

Inflation, a monetary phenomenon

The ECB aims for inflation at just under 2%1. Its policy is based on the understanding that inflation is a monetary phenomenon. This means that in the long run it is determined by the amount of money in the economy. In order to achieve its objective, the ECB depends on the financial system. As a central bank, it does have a monopoly on the creation of official money, but to convert the central bank’s money into financing for the economy, credit is needed. In the euro area, this is mainly done through banks, despite attempts to make the capital markets play a greater role.

The financial crisis at the end of the last decade and the euro crisis have profoundly disrupted the functioning of the financial system. This has put at risk the transmission of monetary policy to the real economy. Like other central banks, the ECB has introduced an arsenal of exceptional instruments since the crisis sprouted in 2007. Two of the most recent and far-reaching of these were the reduction of one of the policy rates to below zero in mid-2014 and the launch in March 2015 of a major programme for the purchase of (mainly) government bonds. The policy rate below zero means banks must pay interest to the ECB if they place deposits with it. This should encourage them to grant credit instead. With the purchase programme the ECB brought long-term interest rates to an all-time low. This makes long-term loans cheaper for households, businesses and the government. The traditional saver pays the bill.

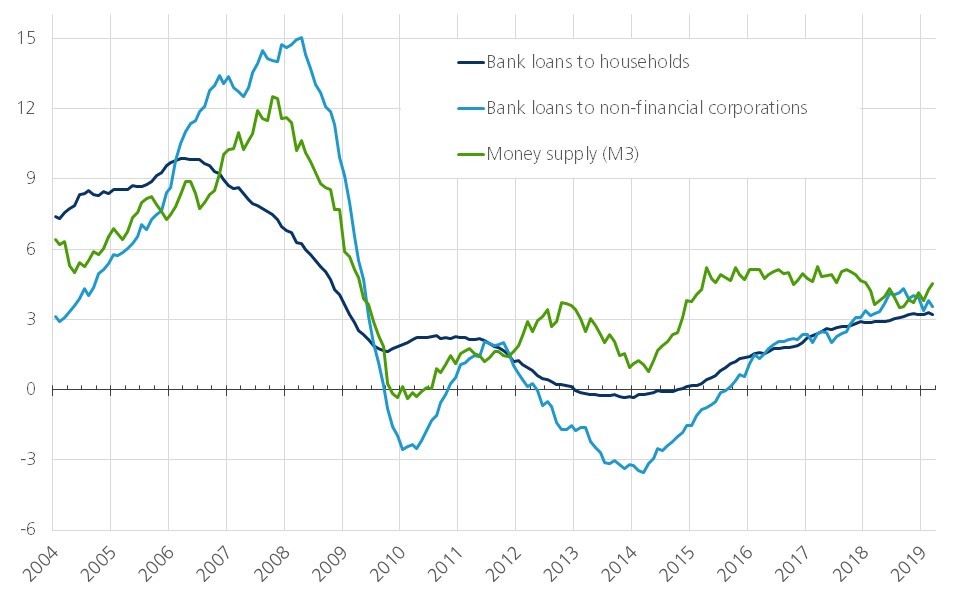

Both measures were adopted in the context of sluggish economic growth and shrinking lending (Figure 1). At the time, the ECB was also concerned about the sharp fall in inflation and inflation expectations. This put its credibility at risk. If the public no longer believes that inflation will be around 2% in the long term, long-term contracts, such as wage agreements, will increasingly take actual, lower inflation into account. Inflation will therefore remain effectively lower. In this context, some feared deflation.

Figure 1 - Bank loans and money supply in the euro area (outstanding amounts, annual change in %)

Limited success

In 2016-2017 the tide turned. Economic growth picked up and lending improved. With its exceptional policies, the ECB managed to avert the threat of deflation and pull credit growth out of the doldrums. However, there was never a strong credit expansion. The year-on-year increase in outstanding bank lending to businesses peaked at 4.3% in September 2018, but it has since slowed to 3.5% in March 2019 (Figure 1). Despite several years of unprecedented monetary stimulus, money growth remained consistently lower than in the period before the financial crisis. The annual increase in the money supply in the broad sense (M3) has averaged around 4.6% since 2015, compared to over 8% on average in 2002-2007.

The result was also limited in terms of inflation. Inflation expectations recovered somewhat, and inflation rebounded, albeit with hiccups and bumps. This reflected the volatility of oil, food, alcohol and tobacco prices. Core inflation shows that there has been hardly any real increase in inflationary pressure2.

What now, ECB?

The 2017 boom was the signal for the ECB to reduce its exceptional measures. At the end of 2018, it ended the bond purchase programme. At that time, it was expected to start normalising its interest rate policy in 2019. Now that the economic slowdown of 2018 has turned out to be more pronounced and protracted than previously thought, it is reconsidering that plan. It is not expected to raise interest rates until 2020 and envisages new, exceptional financing measures for banks. It is also postponing the contraction of its balance sheet.

By keeping its policy extremely flexible for longer, the ECB hopes that inflation will continue to move towards the 2% target. However, it is difficult to see how monetary policy on its own will be able to substantially increase inflation. The low inflation rate does not only reflect the cooling of the economy, but also the restoration of competitiveness by peripheral euro-area countries. This implies that their inflation rates should remain below that of Germany. As long as the German level of inflation remains below 2%, average eurozone inflation cannot really get close to 2%. An inflation rate of more than 2% is not in the offing in Germany. Consequently, a sustainable return of euro area inflation to 2% is a very long-term task.

Meanwhile, loan growth is slowing down. This is no reason to postpone interest rate normalisation. The phenomenon is not abnormal in the context of the weakening of the economy. As the demand outlook fades, companies are less inclined to finance investments with new debts. At the same time, the increase in credit risk is prompting banks to exercise greater caution when granting loans. Moreover, it is not unlikely that banks would currently apply the credit brake a little faster than usual. Indeed, extremely low interest rates with negative interest rates on the money market are eating into the profitability of their core activity: converting short-term deposits into long-term loans. Traditional commercial banks, in particular, are very dependent on their interest rate results and have been relatively hard hit by the ECB’s flexible policy with negative interest rates. The longer the ECB keeps interest rates extremely low, the more it threatens to block the credit lever it needs to make its policies work. The latest ECB survey (Bank Lending Survey) on bank lending policy indicates that higher financial costs and less risk appetite are driving banks to tighten credit requirements.

The ECB continues to believe that if it puts enough money into circulation, inflation will accelerate sooner or later. Our analysis of inflation, however, suggests that this could take a very long time. “In the long run, we’re all dead,” Keynes wrote. Meanwhile, extremely low interest rates create risks to financial stability, not least through the danger of property bubbles and financial bubbles. A thorough reflection on the strategy of monetary policy is called for. It is clear that the ECB will not be able to do the job on its own. The euro area needs a better policy mix. A forthcoming KBC Economic Opinion will be published on this subject in the near future.

Footnotes:

1/ See KBC Economic Opinion of 10 October 2017 on the meaning of this.

2/ See KBC Economic Research Report of 29 April 2019.