In Asia, losers abound in trade war carnage

The US and China have agreed to a 90-day trade war ceasefire during which they will reattempt negotiations. The previously planned increase in the 10% tariff rate currently imposed on $200 billion of US imports from China is therefore on hold, but tensions remain high and the trade war itself is far from over. Many analysts note that there could be regional winners from the trade war, such as in Vietnam, Thailand and Malaysia, as supply chains are disrupted, and businesses look to relocate production. Furthermore, they note that this simply speeds up an already underway trend as China shifts from high speed, export-led growth, to a service- and consumption-based economy with rising wages. Despite the glimmers of optimism, however, the trade war is, without a doubt, a disruptive drag on the global economy overall.

Though escalation of the trade war has been briefly suspended, previously imposed tariffs remain in place and businesses are already feeling the pain. As expected, some companies operating in China have started relocating or making plans to relocate part of their production to other countries. In an American Chamber of Commerce China survey released in September, 74% of respondents (out of 430 companies) said they would be negatively impacted by the then threatened and eventually imposed second round of tariffs. While 65% of respondents said they were not considering relocating manufacturing out of China, for those who are, Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent are the top destinations.

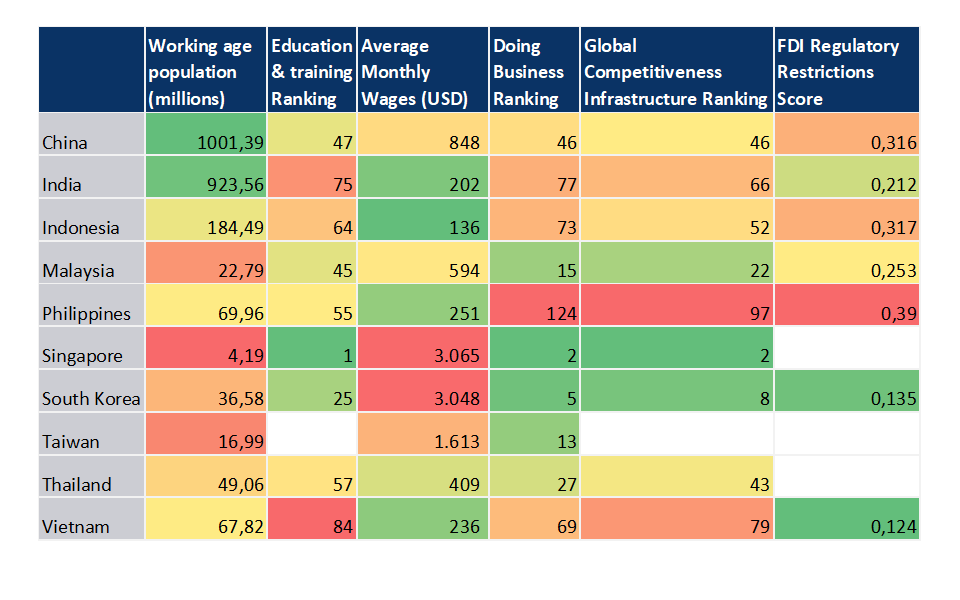

Producers that do move elsewhere will generally look for countries with well-developed infrastructure, a large labour supply, low wage costs, and a favourable business or regulatory environment. While India clearly has the largest potential labour force in the region, several analysts note that Vietnam may also be an attractive destination for shifting production given lower wage costs, existing operations of electronics companies, and its already significant role in apparel manufacturing. As Figure 1 makes clear, however, most economies only have some of these favourable characteristics. In addition, the unemployment rates in several of these economies are already quite low (below 4% in most cases).

Figure 1 - Factors that may impact supply chain shifts

Indeed, despite rising wages, China is still at an advantage when it comes to its significant labour force and established infrastructure. So, although China is in the process of shifting towards a more service- and consumption-based economy, that process, all else equal, should be a gradual one. In other words, manufacturing hubs are not currently directly substitutable, and establishing new global value chains will take time (and foreign direct investment). This explains why a majority of companies aren’t currently considering moving production out of China despite the tariffs. And so, while the disruption of supply chains may mean some countries gain market share, talk of winners from the trade war shouldn’t be misconstrued as optimism about the conflict’s overall impact.

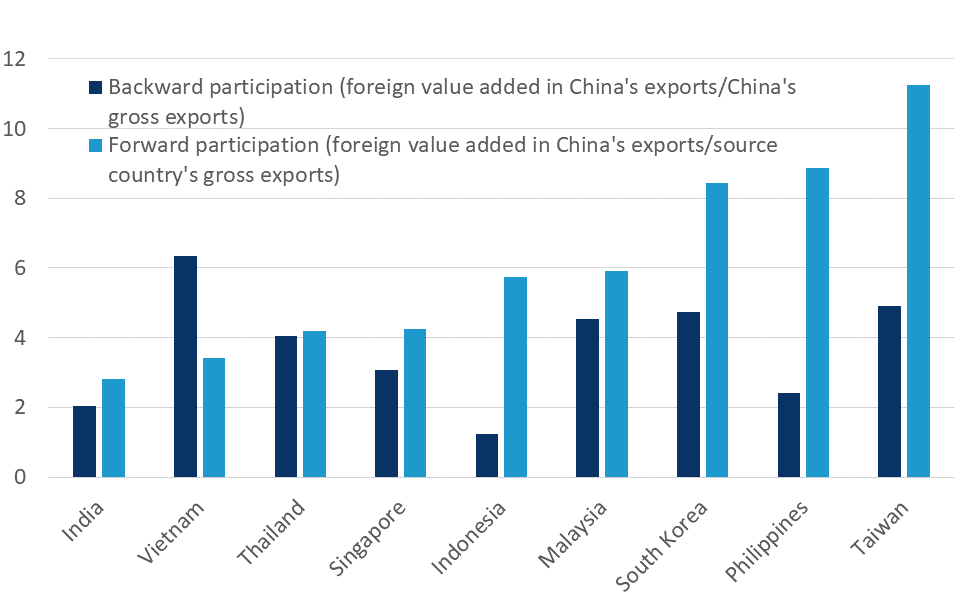

First, those countries exporting intermediate inputs to China, which are eventually re-exported to the US in final goods, will almost certainly be negatively impacted by the tariffs regardless of whether they also gain market share at other stages of the production process (figure 2).

Figure 2 - Supply chain linkages with China (as of 2011), in %

This is because final demand from the US will likely be impacted, and supply chain shifts take time and investment. The result is higher prices and barriers to trade impacting businesses and consumers both within and outside of the US and China. This is consistent with the basic economic view that given comparative advantages, free trade and specialisation maximize efficiency.

Furthermore, academic literature suggests that exporters will absorb a portion of new tariffs by lowering prices and cutting into their own profit margin. One might therefore also wonder if Chinese exporters will try to pass on part of the tariff to neighbouring suppliers by pressuring them to lower prices too. Import price data for China is only available through September 2018, so it is not yet possible to determine whether this is the case, but it will be something to look for going forward.

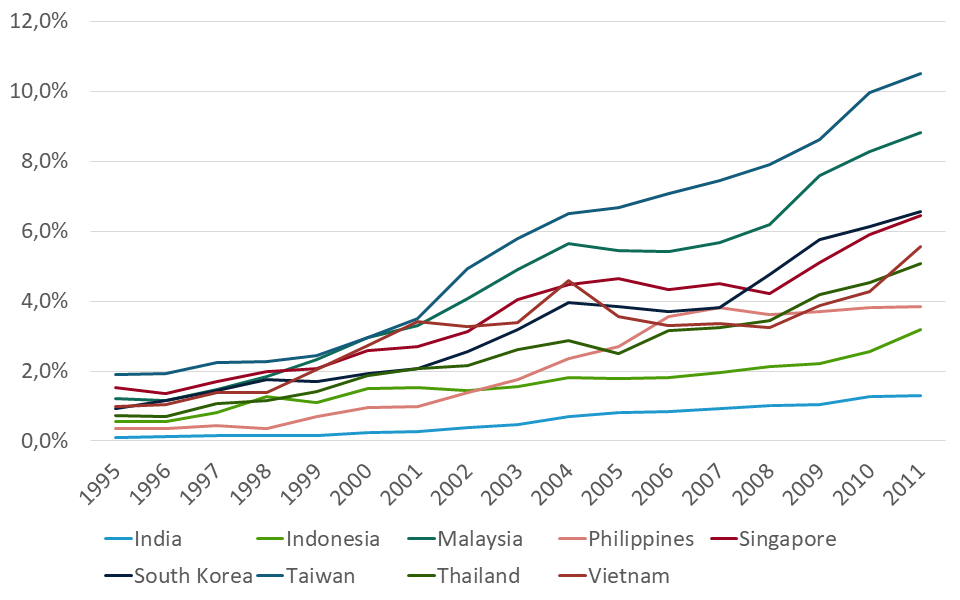

Second, while China and the US should feel the direct impacts of the trade war the most, anything that drags on growth, and therefore demand, in either of the world’s two largest economies is usually a bad sign for the rest of the global economy. This includes the potential “winners” of the trade war given that the region still has sizable exposure to demand from China (figure 3).

Figure 3 - Value added attributable to final demand from China (Foreign value added from country i in China’s domestic final demand/total value added of country i)

The Chinese authorities are currently responding to slowing growth in China by implementing several stimulus measures, but the trade war is certainly not helping their cause. Furthermore, the need for the government to intervene to support growth interferes with their ability to tackle China’s growing debt burden and raises the risk of a hard landing or financial instability in the longer run. Again, a steep decline in growth or any type of financial crisis in China would be highly negative for the other economies in the region.

In sum, there may be a few so-called winners that increase market share as global value chains shift in response to the trade war. However, the risk of escalating trade barriers between the US and China is still a net drag on the global economy. Even those countries that may attract manufacturing could be hurt by the impact of slower global demand and especially a harder landing in China if that risk materializes. As such, to call them winners may be overly optimistic.