Argentina’s credit line with the IMF is a wise move

Argentina is top of mind lately for investors and economic analysts given a significant depreciation of the peso since the end of April, extraordinary measures taken by the monetary and fiscal authorities in response, and news that Argentina has requested a Stand-by Arrangement with the IMF. Though these measures were crucial to stem the peso’s decline and shore-up investor confidence, conditions with the IMF should be carefully arranged to avoid further headwinds to Argentina’s still precarious recovery.

Argentina is no stranger to economic disaster and market turbulence. Optimism among investors flourished, however, when President Macri took power in late-2015. He inherited severe macroeconomic imbalances from his predecessors Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner (President from 2007-2015) and her late husband Nestor Kirchner (President from 2003-2007). Both administrations had financed expensive populist policies through monetization. President Macri, instead, quickly pursued market-friendly reforms and settled with holdout creditors from Argentina’s 2001 debt default (ending a 14-year shut-out from international capital markets).

Despite Argentina’s legacy of debt defaults, its double-digit inflation, and its sizable fiscal and current account deficits (5.9% and 4.8% of GDP, respectively, in 2017), Argentina was able to issue over $40bn in external debt in 2016, 2017, and 2018 together—primarily due to relatively attractive yields. The recent bout of market volatility, though, is a reminder that investor confidence, and Argentina’s economic recovery, remain on shaky ground. Indeed, strong appetite for Argentina’s debt over the past two years is part of a wider global trend, where a “search for yield” may have led to substantial risk taking among investors.

Macroeconomic Imbalances Persist

Argentina’s economy emerged from a recession and registered positive growth in all quarters of 2017, with real annual GDP growth accelerating to 2.9% (YoY) in 2017. The recovery was led by investment growth and strong private consumption. The latter was supported by lower unemployment and higher real wages.

However, strong domestic demand also contributed to robust import growth through 2017. Consequently, the trade deficit widened significantly and has only recently begun to narrow. A severe drought that hit Argentina’s soy industry is expected to weigh further on the trade balance, while any significant deterioration of global trade from a potential escalation of trade conflicts could disrupt the recovery.

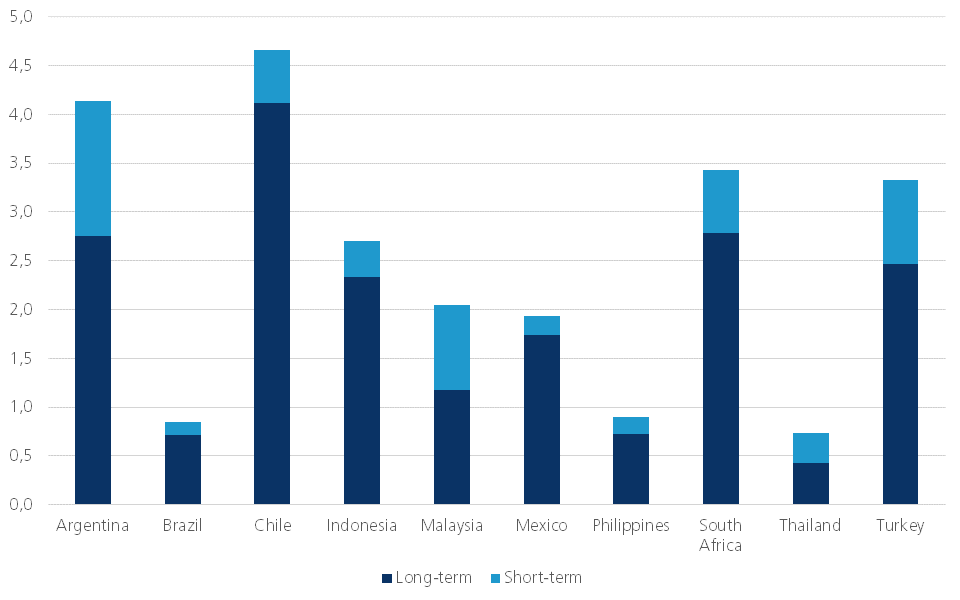

Inflation remains elevated at 25.5% (YoY) in April, significantly above the central bank’s (BCRA) 15% target for 2018. Meanwhile, the external debt burden has risen to 35% of GDP as the government turned to international credit markets to finance its fiscal deficit, adopting a gradual approach to fiscal consolidation. Moreover, though improving, reserve coverage relative to short term external debt is still limited, especially when compared to other emerging markets (figure 1).

Figure 1 - Ratio external debt to international reserves by maturity, Q4-2017

Source: National Authorities

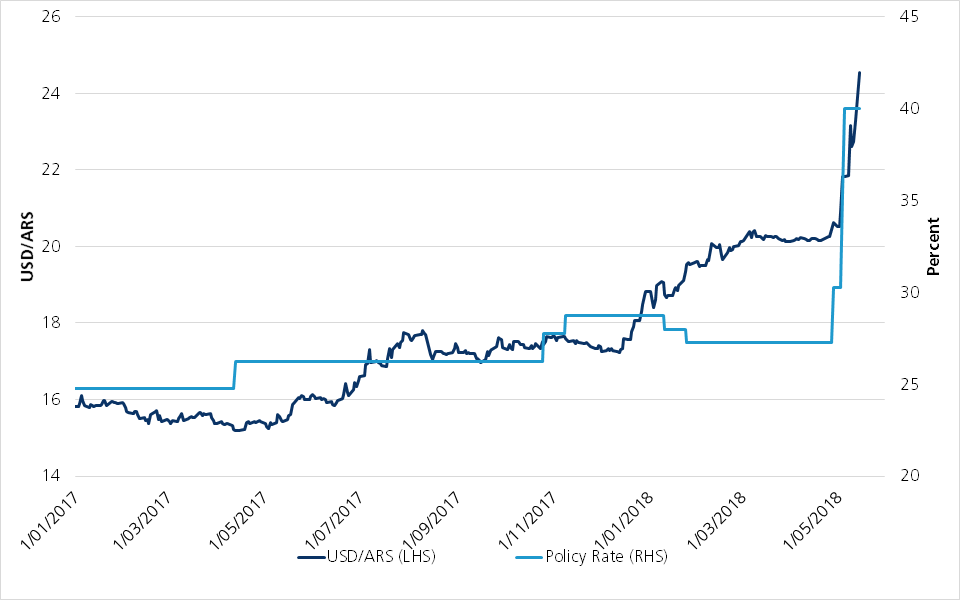

With this macroeconomic backdrop, the peso has been under pressure since the BCRA raised its inflation target at the end of 2017, and eased its policy rate in January this year (figure 2). A steeper slide began at the end of April, along with a broader decline in emerging market currencies, as rising interest rates in the U.S. are expected to present a headwind for emerging market capital inflows. The BCRA increased its policy rate by a cumulative 1275 bps to 40% between 27 April and 4 May, while the fiscal authorities announced a narrower primary fiscal deficit target for 2018 of 2.7% of GDP. Furthermore, the government announced it had requested a high-access Stand-by Arrangement (SBA) with the IMF. High-access precautionary arrangements are established when the recipient does not intend to draw on the available credit, but can do so if necessary (i.e. an additional buffer to bolster liquidity and investor confidence).

Figure 2 -Argentina FX and policy rate

Source: Datastream, BCRA

Considering Argentina’s already fraught relationship with the IMF, the decision to request the SBA and accept specific quantitative conditions (such as deficit targets) is politically risky. Ideally, however, the conditions agreed upon in the ongoing negotiations will align with the government’s current reforms, and can serve simply as a reinforcement mechanism. After all, since taking office Macri’s administration has lifted capital controls, reformed the statistical agency, introduced an inflation-targeting monetary policy framework, and introduced necessary (albeit gradual) fiscal consolidation targets. In Argentina’s latest article IV consultation, the IMF praised authorities for these reforms—a sentiment echoed by IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde last week.

Markets are clearly spooked by the prospect that adverse developments could derail Macri’s gradual approach towards correcting Argentina’s imbalances. Financing the fiscal deficit through external borrowing is not a long-term solution, especially as global interest rates rise, making Argentina relatively less attractive to investors. While Argentina gradually reduces its dependence on external financing, however, investor confidence in its liquidity position is crucial to keep the country on track with its reforms. As such, an SBA with the IMF—before Argentina’s situation deteriorates further—could bolster confidence, while also anchoring Macri’s reforms in place. However, forcing a more abrupt consolidation of the fiscal position could hinder Argentina’s already precarious economic recovery, erode President Macri’s popularity, and diminish support for his economic reform program. Conversely, if arranged right, the SBA is a wise move that could make a successful long-term revival of Argentina’s economy more likely.