Is a green technology war on the horizon?

In 2020 we warned that green competition was coming and judging by the recent flood of Chinese green technology into EU markets at cheap prices, triggering investigations into unfair trade practices and state subsidies, green competition has arrived. In truth, China’s transition to a green leader has been in the works for over a decade and is part of the government’s push to diversify and strengthen economic drivers via industrial upgrading. However, in the context of major headwinds to China’s traditional drivers of growth (i.e. the real estate sector), the push for industrial upgrading has come to the forefront. While China’s investment in technologies that support decarbonisation is net-beneficial for the global climate transition, the massive state-directed support also gives rise to some global concerns, particularly related to supply-demand imbalances, supply-chain vulnerabilities, and the potential for retaliatory trade protection measures. Indeed, European green industries appear particularly at risk. In the current global context, where geopolitical conflicts and risks are already extremely elevated, where the US election in November threatens to give rise to a new trade war, and where the window for getting on an orderly path to net-zero emissions is quickly closing, a green tech war among the major economies would be an unfortunate further blow to global cooperation. This research report discusses how China shaped itself into a green tech leader, and what that means in a fraught global context.

Green competition from China has arrived

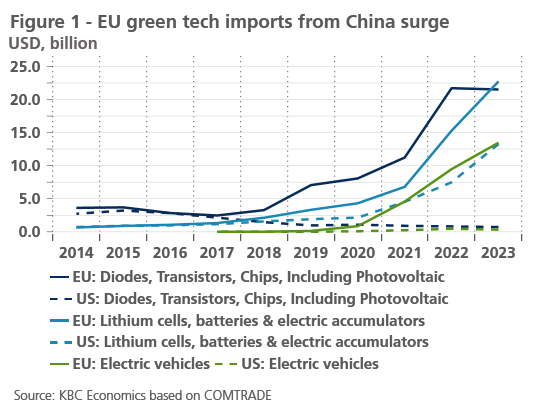

Nearly four years ago, we published an opinion titled “Green competition and opportunities are coming,” warning that the EU needed to act and invest strategically in order to maintain its role as the global leader in climate initiatives and to position itself as a leader in green technology. The piece argued that maintaining a lead in the transition to a green economy was not only important for fighting global temperature increases, but also crucial for maintaining a competitive edge as renewable costs declined vis-à-vis more polluting processes. Four years later, green tech from China—including solar panels, Electric Vehicles (EVs) and lithium batteries—is flooding the EU market (figure 1).

Industrial upgrading in practice

China’s support for what it calls the new three industries (i.e. solar, EVs and lithium batteries) has been in the pipeline for years but has recently been kicked up a gear. The concept of industrial upgrading is integral to policymakers’ efforts to find new drivers of growth and has been grouped into a number of policy pursuits, including high-quality over high-speed growth and a dual-circulation economy. Both involve China moving up the value-added chain, which it has been steadily doing for years, with more of its own value-added present in foreign countries’ exports and less foreign value-added present in its own exports (figure 2). Supporting high-quality green growth was also a major pillar of the fourteenth five-year plan approved in early 2021. The plan targets maintaining manufacturing as a share of GDP while focusing on more advanced manufacturing, increasing R&D spending by 7% per year, reducing the energy and carbon intensity of growth, and reaching peak emissions before 2030.1

Green investment for green-ish growth

To support these policy goals and boost growth amid a real estate crisis and drastically low consumer confidence, China has turned again to what it knows best: state-directed fixed asset investment (FAI), which grew 10% in 2022 and 6.4% in 2023 (private investment grew 0.9% and -0.4%, respectively). Analysis by Carbon Brief, a climate focused media outlet, suggests that clean energy investments accounted for 9% of FAI in 2022 and 13% in 2023, while the statistical authorities in China note that the new three industries accounted for 17.36% of GDP in 2022.2,3 The IEA estimates that such policies have, e.g., helped reduce the cost of solar by 80% over the last decade.4

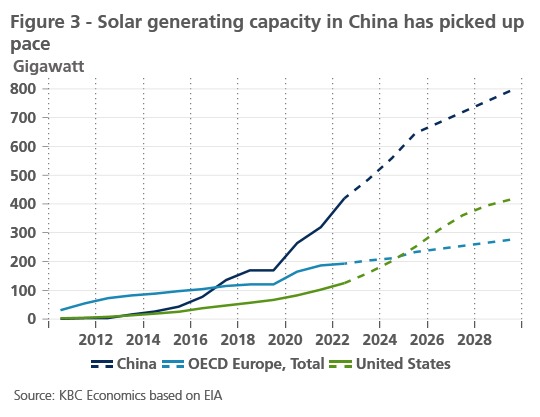

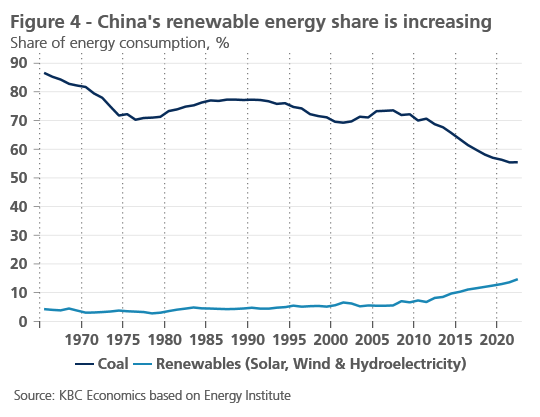

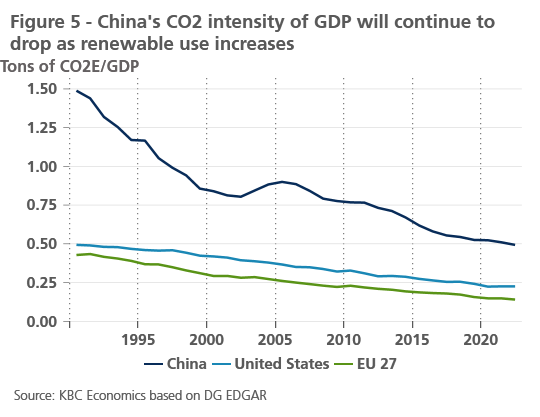

Aside from cheaper labour costs vis-à-vis the EU, China’s competitive price advantage in green tech also comes from its cheap electricity prices. The production of solar panels, for example, requires high heat and significant energy input. While most of China’s energy still comes from coal (meaning the average solar panel needs to function for 4-8 months before it has a net-negative contribution to emissions according to the IEA), China has ramped up its renewable installations in recent years, leading to a higher share of renewables in the energy mix, and supporting a faster drop in China’s emission intensity of GDP compared to the EU or US (figures 3, 4, and 5).

Much of that cheaper, cleaner power is being used for manufacturing, including the manufacture of green tech.5 In the EU, meanwhile, energy prices soared following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, not only hampering industrial production, but also increasing demand for products like solar panels and lithium batteries, which China has been happy to supply.

Is a global green trade war in the making?

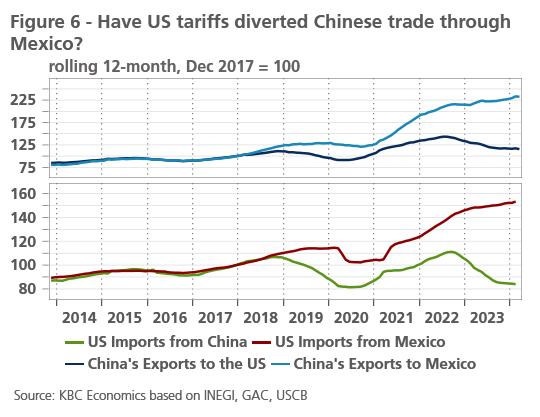

In response, the EU has launched investigations into Chinese state subsidies for solar products, EVs, and wind turbines, alleging that such support is giving Chinese companies an artificial competitive edge by driving the prices lower.6 The investigations could result in countervailing tariff (or equivalent) measures by the EU on China. But China is not alone in providing subsidies to green industries or imposing tariffs to protect such industries. The sharp difference in US vs EU electric vehicle and solar imports from China as seen in figure 1, e.g., likely partially reflects the tariffs imposed by the Trump administration and maintained by the Biden administration on a vast range of Chinese products, as well as Biden-era policies to support investment in domestic solar and EV industries. However, a recent surge in Chinese exports to Mexico, and in Mexican exports to the US, suggests China might be finding a way to circumvent these tariffs (figure 6). The US might try to fight this with stricter rules of origin provisions, especially when the USMCA (formerly NAFTA) is up for review in 2026.

The grey side of green

China’s green tech surge is not without risks or problems. For example, a significant share of China’s solar panel production and an increasing share of EV production comes from the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, from which the US has banned some imports since 2022. Meanwhile, the EU recently reached an agreement that will ban products proven to be linked to human rights abuses, which could raise additional challenges.

Another concern regards the geographic concentration of a significant share of these products’ supply chains. China accounts for over 80% of all manufacturing stages of solar panels, processes 90% of the world’s rare earth elements (important inputs for green technology) and processes 65% of global lithium midstream, creating worrying supply chain vulnerabilities linked to green industries.7,8,9 The EU learned all too well that an over-reliance on one country for crucial imports (e.g., natural gas from Russia) can lead to major economic disruptions.

Conclusion

Though it may seem like Chinese green tech is suddenly flooding the market, China’s rise to green-tech dominance has been years in the making. With the country’s traditional drivers of growth suffering, China is unlikely to step on the breaks soon. This might not be a fully bad thing. Cheap and abundant solar panels and electric vehicles help support the transition to a low-carbon economy and are therefore a crucial element of the fight against global warming. But China’s market dominance has important downsides and threatens the very existence of European industrial core sectors. Against this backdrop, the EU seems to be inching closer to levying countervailing import tariffs on Chinese green products like solar panels and EVs. With geopolitical conflicts and risks already elevated, and a US-led global trade war potentially looming, global cooperation is already on fragile footing. Since global cooperation is indispensable for tackling the climate crisis, policymakers should do their best to avoid a global green tech war while re-levelling the playing field.

Footnotes

2/ Analysis: Clean energy was top driver of China’s economic growth in 2023 - Carbon Brief

4/ Executive summary – Solar PV Global Supply Chains – Analysis - IEA

5/ How China Came to Dominate the World in Solar Energy - The New York Times (nytimes.com)

6/ EU anti-subsidy probe into electric vehicle imports from China (europa.eu)

7/ Executive summary – Solar PV Global Supply Chains – Analysis - IEA

8/ Could Africa replace China as the world’s source of rare earth elements? | Brookings