European fiscal rules: Achilles tendon of the euro area

Autumn is budget time. On 15 October the EU countries have to submit their budgets to the European Commission (EC). Italy is in the spotlight, but other countries are also struggling with a difficult assignment, and the EC is faced with a delicate job. It has to be strict enough to prevent a new debt crisis, but flexible enough not to stifle economic growth. The fiscal framework gives it a lot of room, but its complexity and opacity also risks undermining its credibility. The weakening of the economic outlook makes it even more difficult. Simpler fiscal rules, as recently proposed by the French and German Economic Advisory Councils, are to be welcomed. But without fiscal capacity at the euro area level, fiscal rules will remain an Achilles tendon of the euro area.

At first sight, the EC’s task does not seem so difficult. The fact that a budget deficit may not exceed 3% of GDP and the public debt may not exceed 60% has been enshrined in the European treaties for more than 25 years. However, experience has confirmed economic theory: the rules are too blunt for an optimal fiscal policy. That is why new standards, nuances and exceptions have been added to the fiscal framework. They must allow the EC to assess more accurately which fiscal stance is appropriate. At least two questions are essential.

Needed?

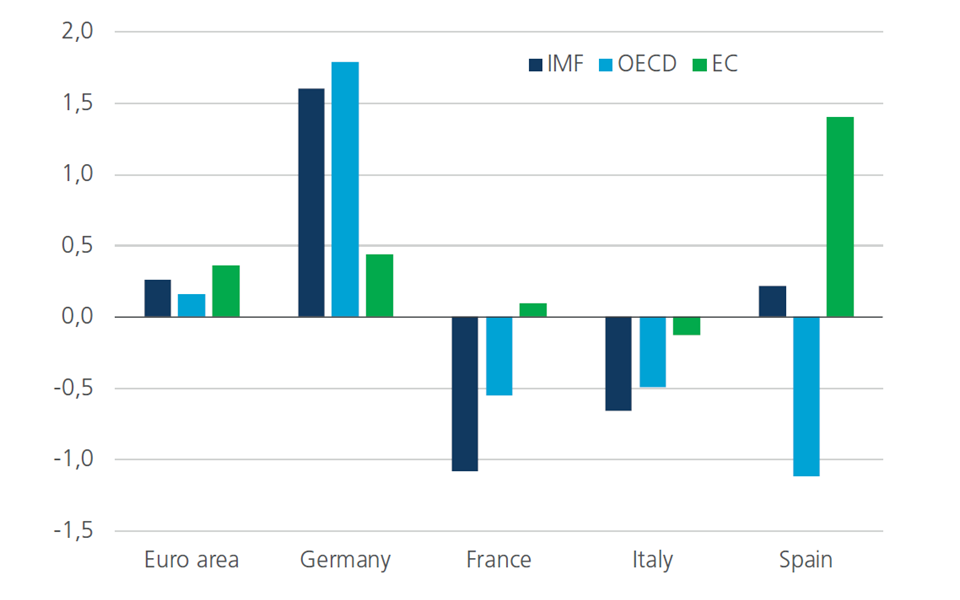

The first examines the state of the economy. Is it going well or not so well? In principle, this is assessed on the basis of the difference between the actual GDP produced and the potentially attainable GDP (the output gap). If actual output is lower than potential, a stimulating fiscal policy, with larger deficits, may be necessary. If the opposite is the case, fiscal reins are best tightened. In practice, however, it is difficult to determine the difference between actual and potential output. Figure 1 shows the estimates by the IMF, OECD and EC of the expected divergence in 2018 for the euro area and its four largest economies. It is immediately noticeable that the estimates may sometimes be very different and may even lead to contradictory messages. For Spain, for example, the OECD expects GDP in 2018 to remain more than 1% below potential, while the EC estimates that Spanish GDP will already be almost 1.5% above potential. The OECD figures can therefore still be used to defend a stimulating policy for Spain, while the EC figures argue for a tighter policy.

Figure 1 - Output gap according to estimates of different institutions (percentage difference between actual and potential GDP, 2018)

Affordable?

Another question is about budgetary room for manoeuvre. If it is clear that the economy needs a stimulus, is there money for it? This is closely related to the level of public debt, interest costs and budgetary decisions taken in the past. The latter will determine the budget balance if policy remains unchanged. Countries with a high public debt and/or a large structural budget deficit have less room for a stimulating policy in difficult times.

The shoe is pinching here. France, Italy and Spain have structural budget deficits. In Italy, the deficit is not very large. But the high public debt and risk premium mean that interest costs remain extremely heavy. The new government wants to pursue a radical expansionary policy. The economic situation in Italy also justifies this. The government has a point to make in this respect, but the budgetary situation does not allow it. The French economy, too, could still use a budgetary stimulus, but has no room for it. A solution could come from the only large euro area country with budgetary scope, Germany. But in economic terms, Germany itself has no need of this. However, this does not alter the fact that a more expansive German policy could benefit the entire euro zone. The complexity of the answers to both essential questions explains why it is difficult to establish an appropriate fiscal policy in the euro area as a whole.

Pitfall

The fiscal framework allows the EC to take a very large number of elements into account when assessing budgets. It can prevent countries from having to adopt too tight a fiscal policy in difficult economic circumstances. That was a criticism during the euro crisis. The EC responded by applying the framework flexibly. Today’s estimates suggest that the negative output gap for the euro area as a whole has been closed. This suggests that there is less acute need for fiscal stimulus. As a result, the question arises whether the EC should make use of the possibility to increase pressure on Member States in economic prosperity, so that they show more fiscal discipline. This is what did not happen sufficiently in the years before the euro crisis. Today it risks becoming another pitfall. While the positive output gap for the euro area as a whole suggests a tighter policy is appropriate, the calculated output gap is small and experience shows that calculations are sometimes substantially revised. As noted, there are also important differences across Member States. Moreover, growth projections are currently being revised downwards. If unemployment also stops falling, this will cast doubt on the opportunity to remove the flexible application of the fiscal framework. The economy may not be strong enough...

But what if the opposite is true? The downward adjustments to the growth forecasts increase the awareness that the peak of economic growth is behind us. But that does not stop growth. From this perspective, budgetary reins should have been tightened earlier and still should be tightened! If a further slowdown in growth were to put further pressure on public finances, such an insight could undermine the credibility of the policy framework. This, in turn, could threaten the stability of the euro area.

Flexibility has the downside that the fiscal framework has become particularly complex and opaque. That in itself is not good for credibility. The German Sachverständigenrat and the French Conseil d’analyse économique have just called for drastic simplification. They propose a spending rule that takes into account the level of public debt and the economic cycle. More simplicity and transparency can only be welcomed. But they are insufficient for a real structural strengthening of the euro zone. This requires that the Member States focus on debt control and that economic stabilisation takes place via a budget at the level of the currency union. To this end, the euro zone itself must be given a fiscal capacity (Economic Opinion 21 Feb. 2017). The EC, President Macron and Chancellor Merkel recently made proposals on this subject, but modestly or for a distant future. In the meantime, fiscal rules will inevitably remain complex, vulnerable to loss of confidence and thus a latent threat to stability. In other words, an Achilles tendon of the euro area.