European housing market awaits less good 2021

The persistently strong price dynamics in European housing markets in the first half of 2020 surprised against a backdrop of the worst post-war economic crisis. In addition to ultra-low interest rates, this was due to government support limiting the loss of income for households affected by the pandemic. Real estate interest from investors also supported the market. It is possible that the deteriorating climate in the European labour market will lead to a correction in house prices with some delay in 2021. Whether and how much prices will fall in individual EU countries remains very uncertain and also depends on the extent to which their housing market is currently overvalued. As the pandemic subsides and the European economies recover, it is likely that house prices will rise again in most countries from 2022 onwards.

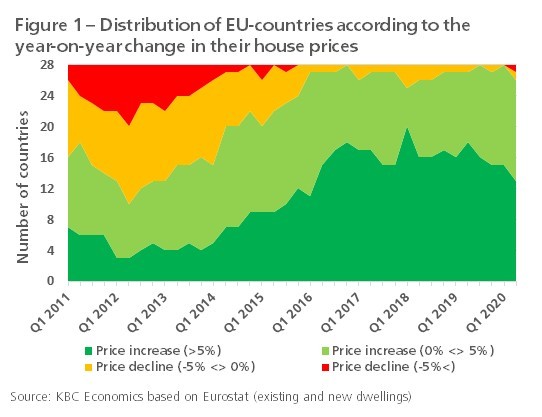

Despite the severe Covid-19 crisis, the European housing market continued to perform strongly in the first half of 2020. According to the latest available Eurostat figures, prices of existing and new houses across the European Union (EU) increased by 5.2% and 4.7% respectively in the first and second quarter compared to a year earlier. This is more than the 4.3% price increase in 2019. In thirteen EU countries, prices still rose by more than 5% year-on-year in the second quarter (figure 1). Only two countries, Cyprus and Hungary, recorded a fall in prices. Although still very robust, the dynamics of price increases at the individual country level seem to have weakened somewhat recently. The number of countries with strong price increases (above 5%) has been declining for several consecutive quarters, and in the second quarter of 2020 price increases slowed in a large majority (i.e. 20) of countries.

The fact that the housing market remained in fairly good shape in difficult economic conditions was due to ultra-low interest rates and the income support that affected citizens enjoyed in most countries (through, among others, the systems of wage subsidies and temporary unemployment). This supported the affordability of real estate. In addition, the combination of low interest rates and an uncertain economic climate fuelled investors’ interest in real estate. In addition to strong demand, the price boom on the European housing market is also due to the slow adjustment of the housing supply. The European Commission’s monthly survey of construction companies shows that supply constraints remained strong in many countries throughout 2020. These include labour shortages in construction, but also restrictions related to lockdown measures in the context of the Covid-19 crisis.

The persistently strong European housing market in a context of severe crisis raises the question of whether the market will overheat and whether the limited slowdown in price dynamics that we are seeing in most countries will finally result in a price correction. In the meantime, the Covid-19 crisis is increasing effective unemployment almost everywhere. In its latest forecasts, the European Commission expects the unemployment rate in the EU to reach 8.6% in 2021, an increase of almost 2 percentage points compared to 2019. The income shock that this will cause will weigh on families’ ability to buy a house. On the other hand, persistently low interest rates and the gradual disappearance of the (uncertainty surrounding the) pandemic could support the housing market. Nevertheless, house prices across the EU may correct on balance in 2021.

Are EU markets overvalued?

Whether and how much prices in individual EU countries will fall depends on their market valuation. After all, the existence of a (substantial) overvaluation of the housing market carries the risk that the expected price correction will (substantially) deepen. The experience of countries such as Spain and Ireland, where the market was hit hard during the financial crisis, shows that the correction can even go so deep that the overvaluation turns into an undervaluation. Such a boom-bust scenario in the housing market has proven to have a very negative impact on the wider economy in the countries concerned.

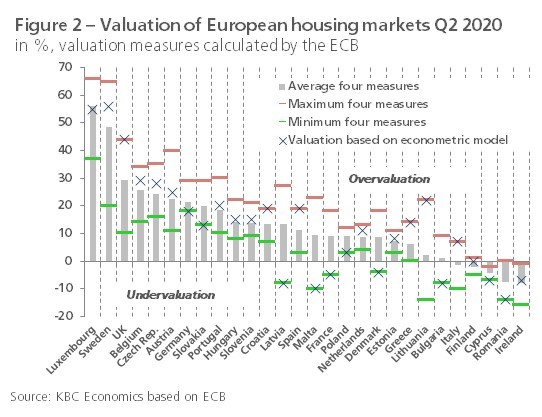

The four valuation measures that the European Central Bank (ECB) calculates each quarter for the EU housing markets show large differences between the countries (figure 2). Especially in Luxembourg and Sweden, but also in the UK (no longer an EU member state but shown here), Belgium, the Czech Republic and Austria, the average of these measures indicates a significant overvaluation in the second quarter of 2020. At the other extreme, Finland, Cyprus, Romania and Ireland are the countries where that average shows an undervaluation of the market. The findings also apply specifically to the ECB valuation based on an econometric model (one of the four measures), which is generally considered to be the most reliable. This model approach estimates an equilibrium price using fundamental determinants (income, interest rates, housing stock…). If the recorded price deviates from this, the model indicates an under- or overvaluation.

An advantage of the econometric approach is that it allows several potential determinants of house prices to be taken into account. However, the ECB does not provide detailed information on which exactly are used for the individual country models. We do know that the variables taken into account may vary across countries, depending, among other things, on their availability over a sufficiently long time series. For example, it may not be households’ disposable income but, as an approximation, GDP per capita that is included in the model. On average, housing markets in EU countries were overvalued by 12.5% in the second quarter of 2020 in the ECB’s model approach. This figure is 14.1 percentage points higher than in the first quarter, suggesting that the sharp GDP correction is weighing on the approach. As a result of government support, household incomes everywhere fell much less than GDP, which suggests that the effective overvaluation has not increased as much as the ECB models suggest. For instance, our own model approach for the Belgian housing market, based on disposable household income, estimates the overvaluation at 10% in the second quarter of 2020, coming from 6% in the first quarter. This is significantly lower than the 29% overvaluation indicated by the ECB’s model for the Belgian market (coming from 5% in the first quarter).

Apart from the uncertain estimates of the market valuation, the still uncertain aftermath of the Covid-19 crisis also means that for the time being it remains very unclear whether and how much house prices in individual EU countries will fall in the coming period. For Belgium, we consider such a (temporary) fall to be likely and currently estimate it at 3% in 2021. However, as the pandemic subsides and the European economies gradually recover, there is also a greater chance that (most) housing markets in the EU will return to positive price developments from 2022 onwards.