Euro area inflation: transitory after all?

Read the publication or click here to open PDF.

The course of inflation in the euro area in recent years has been like a rollercoaster. After a multi-year period of too-low inflation, inflation shot up like a rocket in 2022, followed by an unexpectedly sharp fall in 2023. As the inflation surge was triggered by external factors - the pandemic and, especially in Europe, the energy crisis following the Russian invasion of Ukraine - it was initially labelled transitory, not only in Europe but also in the US. Only when the risk of a wage-price spiral became evident did fears of high inflation becoming permanent prevail. It prompted the European Central Bank to raise interest rates from an all-time low to a historic peak at record speed after the Federal Reserve in the US had acted earlier. The unexpectedly sharp drop in inflation in 2023 and financial markets' reaction to it in the final weeks of 2023 may give the impression that the fight against excessive inflation has been won and that the inflation surge was therefore a transitory phenomenon after all, lasting, at most, a little longer than initially expected.

This conclusion is premature because - especially in the euro area - the fall in inflation in 2023 was mainly the result of the sharp fall in energy prices, again an external factor. From the second half of 2023 onwards, this caused sharp declines in inflation mainly for technical reasons (so-called base effects). Those have now worked out. Moreover, while the risk of a wage-price spiral has been reduced, it has not been eliminated. Such a spiral is the biggest risk for permanently higher inflation. KBC Economics expects that risk to remain under control, but without a tailwind from base effects, inflation cooling will slow. The last mile is the hardest. Only when the risk of a wage-price spiral is fully contained can it be concluded that inflation has been durably reduced to near the 2% target. That will only be possible during 2024. Whether the inflation surge will then - in retrospect - have been transitory or not is then likely to become a semantic debate. Transitory, indeed, because it was quickly overcome. But also at least potentially permanent, because a drastic intervention of monetary policy was needed to make the victory possible. Looking back at the inflationary rollercoaster and its past history, it may also serve as a reminder that monetary policy is more effective in the fight against high inflation than against low inflation.

Unprecedented inflation surge…

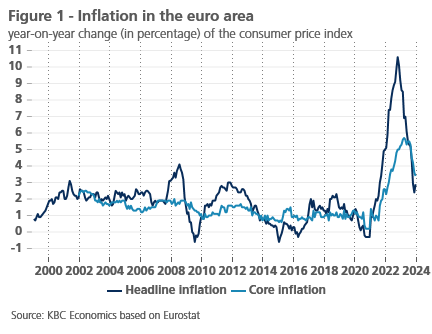

The course of inflation in the euro area in recent years has been like a rollercoaster. After the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09 and the subsequent European debt crisis, inflation almost drove the European Central Bank (ECB) to despair by settling stubbornly well below the 2% target for a decade. Despite negative interest rates and an arsenal of other unconventional monetary measures, the ECB failed to sustainably increase the inflation rate, which was too low according to its target. Then came the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia's invasion of Ukraine, which triggered an unprecedented energy price shock and a surge in food prices, among other things. Inflation shot up like a rocket, reaching 10.6% in October 2022 (Figure 1). Core inflation also climbed significantly higher, albeit slower than overall inflation, but steadily. For years, core inflation had settled around 1%, but in late 2021 it rose above 2% for the first time in almost two decades, peaking at 5.7% in March 2023.

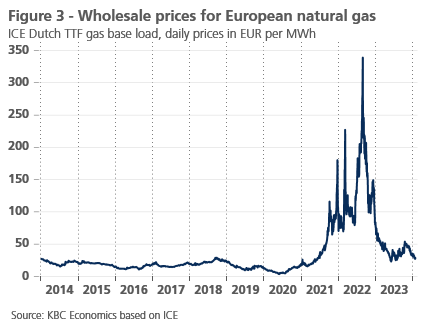

What extreme monetary policy had failed to do for years was suddenly caused by external factors: more inflation, even too high inflation. The pandemic had disrupted numerous supply chains, resulting in sometimes large supply shortages, while lockdowns forced households to adjust their consumption patterns. This disrupted price formation and hence inflation, initially still downwards but then sharply upwards. The shocks to economic activity caused by the pandemic were also reflected mainly in energy prices. These too fell initially, but then rose sharply, especially in Europe. There, the Russian invasion of Ukraine seriously disrupted gas supplies, resulting in exuberant increases in natural gas prices (see below). Markets for agricultural products were also disrupted, in some cases also because harvests were disappointing due to extreme weather conditions caused by climate change, while rising energy prices further drove up food transport and processing costs.

Rising energy and food prices, in particular, put a turbo under the inflation acceleration. They provided higher-than-expected inflation rates month after month from late 2021 until the peak in October 2022. Meanwhile, reopening effects after the pandemic clouded the picture of underlying inflation dynamics. For instance, the rise to above 2% in core inflation, which excludes energy and food prices, in the final months of 2021 was due not only to exceptionally large price increases in the post-pandemic reopening of the economy, but also to so-called base effects resulting from the exceptionally flat price trend during the lockdowns a year earlier.

... initially considered transitory

That a long period of fruitlessly fought too-low inflation was followed by a period of far too-high inflation was not an immediate reason for the ECB to drastically adjust its policy. Indeed, precisely because high inflation had been caused by external factors, the ECB - and many economists with it - initially saw the inflation surge as a transitory phenomenon.

At its December 2021 policy meeting, the ECB did decide that "a gradual reduction in the pace of our asset purchases 1 over the coming quarters became possible". But although it noted in March 2022 that inflation was becoming "more widespread", it then still considered it "increasingly likely that inflation will stabilise at its two per cent target over the medium term". The communiqué after the policy meeting in early March 2022 still stated that it would keep its base interest rates at the historically low level until it was established that "underlying inflation has made sufficient progress such that it is consistent with the stabilisation of inflation at two per cent over the medium term". At the same time, the ECB pointed to uncertainty "due to the role of transitory pandemic-related factors and the indirect effects of higher energy prices". The ECB therefore made future policy decisions more "data-dependent", which would rely on "optionality, gradualness and flexibility".

... still prompts drastic interest rate hike

Inflation rose to 7.4% in March 2022, one and a half percentage points higher than the previous month. Only at its June 2022 policy meeting - when inflation exceeded 8% - did the ECB call "high inflation a major challenge for all of us" and immediately added: "The Governing Council will ensure that inflation returns to our medium-term objective of two per cent". The ECB announced an increase of the base interest rates by 25 basis points in July 2022, and put further interest rate hikes on the horizon.

Inflation rose to 7.4% in March 2022, one and a half percentage points higher than the previous month. Only at its June 2022 policy meeting - when inflation exceeded 8% - did the ECB call "high inflation a major challenge for all of us" and immediately added: "The Governing Council will ensure that inflation returns to our medium-term objective of two per cent". The ECB announced an increase of the base interest rates by 25 basis points in July 2022, and put further interest rate hikes on the horizon.

The ECB thus acted several months later than the US Federal Reserve (Fed). The latter had already raised its policy rate by a quarter of a percentage point to 0.25%-0.50% for the first time in mid-March 2022. After all, inflation had also risen sharply in the US, and a debate between a "temporaryists" camp versus a "permanentists" camp had unfolded among economists. The Fed switched camps slightly earlier than the ECB, admittedly also because economic conditions in the US differed from those in the euro area.

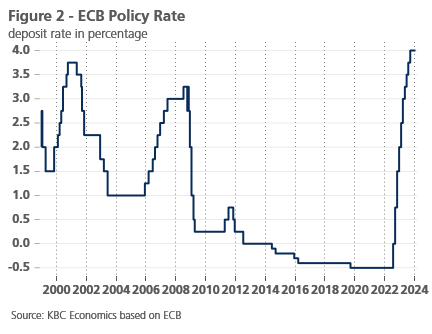

After July 2022, the ECB would raise its policy rate nine more times, causing deposit rates to rise at a record pace from their historical low (-0.25%) to their historical high (4.0%) by September 2023 (Figure 2). Indeed, the ECB had become convinced that the sharp rise in inflation could no longer be seen as a transitory, passing phenomenon. If expectations for future inflation increased or if the loss of purchasing power of wages gave rise to higher nominal wage increases 2, the external inflation shock would become permanently embedded in the economic tissue. Excessive inflation threatened to become not a transitory but a permanent feature.

The tightness of the labour market made this threat very real. The structural difficulty in finding suitable labour encouraged employers to keep their workers on the payroll as much as possible, even during periods of weak activity (labour hoarding), while extensive government support gave an additional push for this. Government support also helped to make household consumption demand very resilient in 2021-2022, often allowing companies to pass on their increased costs to a large extent in their sales prices. Their profit margins were thus maintained or sometimes even increased. Many conditions were met to trigger a wage-price spiral. However, by raising interest rates sharply, the ECB would dampen demand and stifle these so-called second-round effects of energy price increases on inflation.

Sharp drop in inflation...

Since late 2022, consumption demand in the euro area has broadly stalled (although with differences between countries and Belgium as a relatively positive outlier) and inflation has fallen dramatically to 2.4% in November 2023. Core inflation then stood at 3.6%, more than two percentage points lower than its peak in March 2023. Especially in autumn 2023, the inflation decline was stronger than expected.

As a result, financial markets in the last weeks of 2023 cast considerable doubt on the hitherto fairly general expectation that central banks would keep their policy rates at a high level for a long time, not only in the euro area, but also in the US. There, markets seemed to assume that the Fed had overcome inflation and would once again pay more attention to its second policy objective of full employment3. It caused a spectacular fall in long-term interest rates. Market expectations for euro area inflation, as reflected in inflation swaps, also declined.

Fears that the two per cent inflation target would be substantially exceeded for a long time and high inflation would thus become a more or less permanent feature thus seemed to be reversing somewhat, at least in financial markets. So, was the post-pandemic inflation surge after all only a transitory phenomenon, which at most lasted a little longer than initially expected?

... but the last mile is the hardest

A positive answer to this question would sound premature. Certainly for the euro area, a first reason for this is that the recent spectacular fall in inflation - like the rise before it - is due to an external factor, namely the sharp fall in energy prices, in particular European gas prices. This peaked at an average of 236 euros per megawatt-hour in August 2022, 530% higher than a year before and 15 times higher than the average price in 2014-2019 (Figure 3). But in the second half of 2023, it again averaged "only" 38.3 euros per megawatt-hour. While that is still more than double what it was before the pandemic, it is more than 80% less than the August 2022 peak. The steepest decline occurred in the period September 2022-March 2023. With much lower intensity, the price of Brent crude oil in the commodity markets experienced a more or less analogous development.

With some delay, and somewhat tempered by government measures, these price fluctuations translated into the consumer prices of energy products. An initial spectacular rise in energy prices was followed by a spectacular fall. Initially, the fall in inflation was the result of those falling energy prices themselves, but when that fall was largely over by March 2023, the further fall in inflation was essentially only due to a technical feature of the measurement method.

Namely, inflation is measured as the change in the general price level from a year earlier. Since spring 2023, the year-on-year decline in energy prices was increasingly only due to the higher basis of comparison one year back, rather than a decrease in energy prices versus the previous month. These so-called base effects were the main cause of the spectacular fall in headline inflation during 2023 but have now largely worn off. It explains why euro area inflation rebounded to 2.9% in December 2023 from 2.4% in November.

A new, further fall in inflation is likely during 2024 and beyond, but it will be considerably slower and more volatile than in 2023, as it will have to come mainly from cooling core inflation. It is true that energy prices are expected to have a neutral to slightly negative impact on inflation in 2024, although this expectation is very uncertain, not least due to high geopolitical uncertainty and the energy transition as part of the fight against climate change. However, a similarly strong negative inflation impulse as in 2023 due to energy prices seems almost out of the question in 2024. Food price inflation is also expected to cool further but remain well above two per cent. And that too remains particularly difficult to predict because of geopolitical uncertainty and climate change. So not only will inflation fall more slowly, it is also more sensitive to shocks.

A sustainable return of inflation to the two per cent target requires a further cooling of core inflation. It too is falling, but less spectacularly than overall inflation: from 5.7 per cent in March 2023 to 3.4 per cent in December. The decline was sharpest in goods (excluding energy products): from 6.6% in March to 2.5% in December. Compared to the previous quarter, goods prices even remained unchanged on average in the fourth quarter, at least when typical seasonal price adjustments are excluded.

Services inflation (the other component of core inflation) cooled even more slowly. It also got off to a later start. Indeed, services inflation only peaked (at 5.5%) in June and July 2023. Since then, it has fallen to 4.0% in December 2023. That is still almost double the target. The rate of increase over the short term also remained above the target. After adjusting for seasonal variation, service prices in the fourth quarter of 2023 were 2.2% (annualised) higher than in the previous three-month period.

The evolution of core inflation makes it clear that the inflation upsurge of recent years is far from being overcome. In particular, services inflation is very sensitive to the second-round effects of wage increases. That process is still in full swing, which is the second major reason why it is premature to definitively conclude that the inflation surge was transitory after all. The process is therefore being watched with great attention.

The ECB indicator on wage agreements pointed to a year-on-year increase in negotiated wages in the euro area of 4.7% in the third quarter of 2023 compared to year-on-year growth of 3.1% a year earlier and only 1.1% in the third quarter of 2021. Against the backdrop of the massive inflation surge, this acceleration in the pace of wage growth is, at first glance, rather not so bad. But the annual increase in labour costs per unit of output, at 6.1% in the third quarter of 2023, was still significantly higher than the agreed wage increases. Indeed, the resilient employment development in the context of slack economic activity has the downside of falling labour productivity. This reinforces wage cost growth. Inflation can then cool only if companies cut back on their profit margins, which is already happening to some extent at present.

But ECB president Christine Lagarde pointed out at the press conference after the ECB policy meetings in December 2023 and January 2024 that the wage agreements of about half of the workers whose wages the ECB monitors will still be renewed in the first half of 2024. Not coincidentally, then, she stressed that the ECB needs more data.

The ECB wants a fuller view of what is happening in terms of wage cost growth and profit margin development. In the meantime, it remains "determined to ensure a timely return of inflation to our medium-term objective of 2%" and will "ensure that our key interest rates are set at sufficiently restrictive levels for as long as necessary". So reads the press release after the December 2023 and January 2024 policy meeting. A reduction in vigilance is not considered by the ECB at all.

Conclusion

KBC Economics expects that wage growth will not derail and that a significant part of the wage cost increase will indeed continue to be absorbed by profit margins. As the euro area economy gradually picks up in the second half of 2024, spurred by, among other things, the purchasing power recovery, productivity gains will resume. As a result, wage cost pressures may gradually ease, while the demand recovery is not expected to be sufficiently robust to create strong upward price pressures. In such a scenario, a further cooling of domestic inflationary pressures is likely. But this will be a gradual process. The ECB is still expected to wait to cut its policy rate until its June policy meeting, when economic data further confirm that this scenario is effectively unfolding.

Whether the inflation surge will then - in retrospect - have been transitory or not is then likely to prove a semantic debate. Transitory, indeed, because it was quickly overcome. But also at least potentially permanent, because a drastic intervention of monetary policy was needed to make that victory possible. Looking back at the inflationary rollercoaster and its preceding history may also serve as a reminder that monetary policy is more effective in the fight against high inflation than against low inflation.

1 Systematic buying of financial assets, such as government bonds, in the financial markets was one of the unconventional measures taken by central banks (quantitative easing) in the fight against too-low inflation.

2 In Belgium, this is done automatically through the indexation of wages to the health index

3 Unlike the ECB, which has only price stability as the main objective of its policy, the Fed has a dual policy objective: full employment in addition to price stability.