Energy crisis and consumption

Inflation curbs Belgian consumption growth, but how much?

- 1. Theoretical effects of inflation

- 2. Private consumption during previous inflation shocks

- 3. Outlook KBC Economics

- 4. Uncertainties and longer-term effects

Read the publication below or click here to open the PDF.

Abstract

It is striking that, till the third quarter of 2022, the energy crisis and the resulting high inflation had no visible impact on the volume growth of private consumption in Belgium. The transmission of (high) inflation to household spending is a complex interplay of many possible theoretical effects. That these are far from always manifesting themselves in practice is because mitigating factors are at play (such as the automatic indexation of wages and social benefits) that reduce or largely cancel out the inflation impact. Monthly indicators available nevertheless suggest that Belgian households in particular have become increasingly cautious about their planned major purchases. KBC Economics therefore believes that private consumption will have fallen in the last quarter of 2022 and will stagnate in the first quarter of 2023. From spring 2023, consumption dynamics will recover. That the inflation impact on household consumption will have been limited on balance implies that the inflation shock is passed on to businesses and the government. The flip side of steady consumption in the short term is that the profit margins and competitiveness of firms as well as public finances deteriorate. That means less investment and exports and more fiscal consolidation in the somewhat longer term, undermining the economy's growth potential and also the potential for consumption in that term.

1. Theoretical effects of inflation

Because household consumption (like many other economic variables) is a behavioural variable, it is difficult to capture in practice. According to the consumption function developed by John Maynard Keynes, two factors play an important role in explaining consumption: the evolution of real disposable income (i.e. purchasing power) and the extent to which that income is consumed or saved (i.e. the rate of consumption or, put differently, one minus the savings rate). Both are in turn determined by a multitude of other factors: job creation, changes in income taxes or social benefits, consumer confidence,... Besides the income-dependent part of consumption, there is also so-called autonomous consumption. This arises, for example, when households draw on present savings or take out consumer credit.

Multiple transmission channels

Inflation can affect several of these determinants. The most visible and obvious impact is on real disposable income. Inflation erodes the purchasing power of nominal income if no measures are taken to offset it, such as raising wages (e.g. through indexation) or granting a subsidy. Nominal income can also be affected by inflation if the latter more generally damages economic activity. This would be the case, for instance, when relatively high inflation affects the competitiveness of firms, leading to job losses. The impact of inflation on autonomous consumption is also often unequivocally negative: after all, it also affects the purchasing power of savings and makes credit more expensive via higher interest rates.

In addition, there are often psychological effects. If prices rise abnormally, consumers suddenly become a lot more cautious and adjust their spending. For instance, widespread media coverage of high inflation may provoke panic reactions, causing people to hit the consumption brakes. Even when wages and social benefits are indexed to increased inflation, the perception of impoverishment may arise. Laboratory experiments also show that consumers give more weight to price changes to which they are regularly exposed, such as daily or monthly spending on bread or energy1. If those goods or services then rise relatively sharply in price, this can distort wider consumption behaviour.

In practice, psychological effects will usually lower the rate of consumption (i.e. what part of an extra euro of income is consumed). Yet, high inflation can also have the opposite effect on the rate of consumption. Indeed, fearing further sharp price rises, people may tend to consume just more from disposable income today (e.g. in order to stock up on supplies, accelerate the replacement of durable goods or bring forward an already planned purchase). Put another way, expectations of persistently high inflation may make people prefer not to save (lower savings rate). After all, with the money set aside now, consumers can buy fewer goods and services later. To the extent that this phenomenon occurs, although it causes early consumption, it weighs on later consumption opportunities. This so-called intertemporal substitution will mainly occur when buying durable goods, such as a new car or refrigerator.

Note further that high inflation can also cause (some) people to consume differently rather than less (e.g. choosing a cheaper alternative, holidaying at home instead of abroad, eating more at home instead of going out to restaurants). Again, and perhaps paradoxically, in some cases this may even lead to more consumption (e.g. buying in bulk because it is cheaper per unit).

Specific circumstances

Besides the effects mentioned, the relationship between inflation and consumption is also partly determined by the nature of the inflation shock, the institutional framework and the government's policy response. For instance, there is a substantial difference between inflation arising from a (positive) demand shock and inflation from a (negative) supply shock. In case of a negative demand or supply shock, rising inflation is accompanied by falling consumption, while in a positive demand shock, rising inflation is accompanied by (read: a consequence of) rising consumption2. Automatic stabilisers, such as wage indexation or a strong social safety net, will (partially) cushion high inflation, making the impact on consumption smaller or even non-existent. The same applies when the government takes specific ad hoc measures (subsidies, VAT reduction,...) to preserve households' purchasing power.

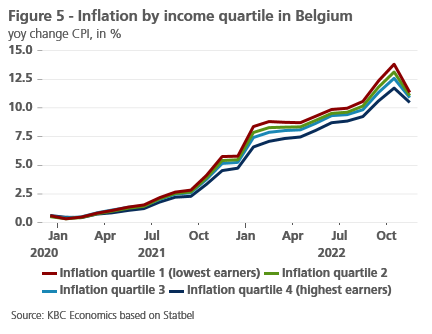

Finally, note that published inflation rates reflect an average consumption pattern across all households. Since individual households have their own consumption preferences and capabilities, perceived inflation will differ across households, especially between those with different income categories. This also implies that the impact of inflation on consumption can vary greatly at the micro level, depending on the source of inflation (increase in food prices, energy prices,...). Moreover, in case of wage indexation, individual households may be over- or under-compensated.

2. Private consumption during previous inflation shocks

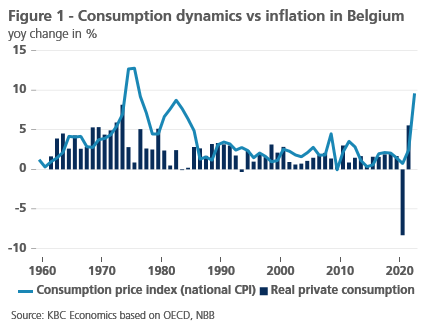

The multiplicity of transmission channels and complex consumer behaviours complicate the estimation of the inflation impact on aggregate consumption. Ultimately, the question of inflation's impact on consumption remains an empirical one. A quick back-of-the-envelope exercise already points to an unexpectedly direct correlation (see Figure 1). The correlation between inflation (i.e. the annual increase in the national CPI) and consumption dynamics (i.e. the annual change in real private consumption) in Belgium over a long period (1961-2021) actually turns out to be positive (correlation coefficient 0.20). An obvious explanation for the absence of a clear negative correlation is that in times of low normal inflation, other consumption determinants (e.g. job creation) play a more decisive role.

It is not clear from what level inflation can start having an impact on private consumption. Economists assume that moderate inflation is not harmful. After all, it usually reflects a trend improvement in the quality of goods and services purchased and lubricates the economic engine. One could identify an inflation shock as a period when inflation climbs a certain number (e.g. two) of percentage points above the average of the previous period (e.g. four previous quarters). But even then, realised inflation may still remain rather low, without much impact on consumption. Hence, the economic literature tends to look for a tipping point or threshold above which inflation begins to "bite" consumption, or more generally economic growth. For instance, an econometric study by Kremer et al (2013), based on a threshold regression model, puts that threshold at 5% for developed countries3.

In Belgium, there were only four periods since the 1960s when inflation exceeded 5%. This was the case during the first oil price shock (from Q3 1971), during the second oil price shock (from Q4 1979), very briefly during the financial crisis (from Q2 2008) and most recently during the energy crisis (from Q4 2021). Figure 2 shows these periods. The longest period was during the first oil price shock, when high inflation (>5%) persisted for 26 quarters. During the second oil crisis, it was 23 quarters, during the financial crisis only two quarters. The recently high inflation during the prevailing energy crisis already covers five quarters and will continue to average above 5% for three more quarters (the first three in 2023), according to KBC Economics' latest outlook.

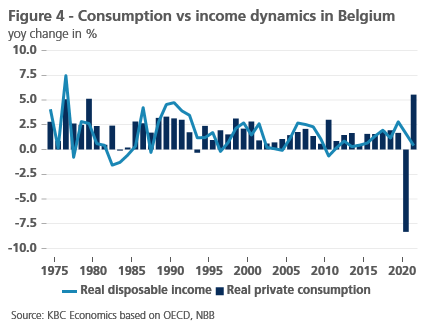

Figure 3 shows the year-on-year change in real consumption of Belgian households during the four periods of high inflation. It is notable that, apart from a few quarters of negative or zero growth, consumption held up well during each period. The relative resilience of consumption in times of high inflation is probably explained by the fact that Belgium has many mitigating factors in place that reduce or largely eliminate the impact of inflation. These are automatic stabilisers that are partly institutional in nature, including the system of automatic indexation of wages and social benefits and the existence of social tariffs on many goods and services (energy, telecoms, social housing, doctor's visits, etc.). These help keep the purchasing power of households somewhat intact. Hence, consumption dynamics (i.e. the annual change in real private consumption) shows a better correlation with income dynamics (i.e. the annual change in real disposable income). For the period 1971-2021, the correlation coefficient between the two is 0.50 (see Figure 4).

3. Outlook KBC Economics

Since the 2008-2009 financial crisis, the temporary unemployment system has also been extended, while the relatively rigid and tight Belgian labour market has recently been increasingly associated with labour hoarding (i.e. the hoarding of labour during an economic downturn in order not to endanger future production potential). As a result, the impact of negative shocks, including the recent surge in inflation, on the labour market remained relatively limited. More so, in the first three quarters of 2022, domestic employment in Belgium was on average 108,000 units higher than in the same period in 2021. Moreover, in the latest corona and energy crises, there was broad government support to a large share of households. Finally, there was significant pent-up demand from Belgian consumers after the pandemic in 2022. All this explains why consumption still held up well despite two shocks that occurred in quick succession. In the first three quarters of 2022, private consumption volume growth was almost 5% higher than in the same period a year earlier.

Nevertheless, leading indicators available on a monthly basis suggest that consumers have become increasingly cautious about their planned major purchases, in particular consumer durables (see also box on pages 5-6). The situation on the labour market also seems increasingly bleak, with significantly less net job creation and somewhat rising unemployment in 2023. Note further that the average good protection of households against the energy crisis hides differences between individual households. Since households from lower income categories spend relatively more of their budget on energy, they are proportionally more affected by the current crisis (although inflation differences between income categories are not very large, see Figure 5). Those households may therefore scale back their consumption somewhat more.

As a result, KBC Economics still assumes that private consumption will have fallen somewhat in the last quarter of 2022 (-0.1% compared to the previous quarter) and will probably stagnate in the first quarter of 2023 (i.e. zero growth compared to the previous quarter (see table 1). This is the main reason why our baseline scenario also assumes a slight contraction in real GDP growth in Belgium in the fourth quarter of 2022, followed by stagnation in the first quarter of 2023. From spring onwards, consumption growth is likely to recover. Thanks to the combination of delayed wage indexation and a gradual softening of inflation, households' purchasing power should rise throughout 2023. Specifically, we see their disposable income rising by 2.0% in real terms this year compared to 2022.

4. Uncertainties and longer-term effects

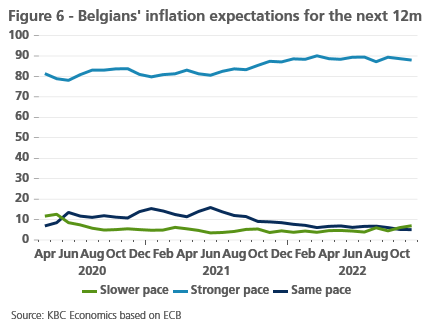

Nevertheless, considerable uncertainty remains. For instance, the inflation path through 2023 remains highly dependent on the further development of energy prices. Consumer behaviour may also undergo longer (negative) psychological effects. Although the automatic indexation largely mitigates the inflation impact on income in reality and the government supports households for the higher cost of energy, an Ipsos survey in December 2022 shows that just over half of Belgians still fear they will have less disposable income in 2023. This is because the majority of consumers (88% in November 2022) still expect a stronger rate of inflation over the next 12 months (see Figure 6).

Finally, the softening factors for household income also imply that the inflation shock will be passed on to businesses and the government. In other words, the flip side of relatively firm consumption in the short term is that the profit margins and competitiveness of companies as well as public finances deteriorate sharply. This is likely to imply less investment and exports and more fiscal consolidation in the somewhat longer term. This could then undermine the growth potential of the Belgian economy and also the consumption opportunities of Belgians in that term.

Box - Leading indicators point to weaker demand

It is generally accepted that the consumer confidence indicator is a good help in the early estimation of effective household consumption. However, the correlation between the change in consumer confidence and consumption growth has not been very high in Belgium in recent decades1. Over the past 1.5 decades, it was even surprisingly low. The same was true in 2022: the sharp fall in confidence contrasted sharply with the sustained increase in consumption through the third quarter. In November, December and January, consumer confidence improved, but was still well below the long-term average. There are several reasons why changes in consumer confidence and consumption do not always coincide nicely. First, public sentiment tends to be more erratic than effective consumption. Consumers sometimes think extremely positive or negative about the general economic and political situation, but as long as it has no significant impact on their own financial situation, their willingness to buy is not adjusted proportionally. The relative volatility of confidence is also explained by the fact that, in addition to economic and political influences, psychological factors operate on confidence (e.g. Russia's invasion of Ukraine). Given the instability of the relationship, caution is needed when drawing conclusions about consumption growth from confidence.

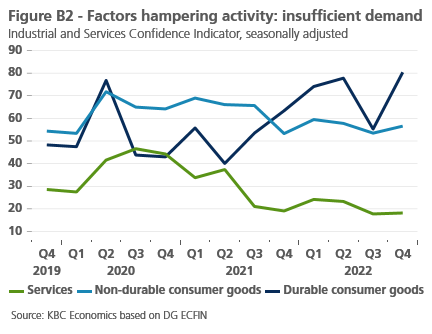

Consumer confidence is therefore best evaluated in conjunction with other leading (confidence) indicators of consumption, such as hard data on retail sales, firms' expectations of demand or labour market developments. After improving until the late summer months, the year-on-year dynamics in retail sales declined again in October and November. Figure B1 shows that retailers' expectations of future demand (+3m) also fell to a very low level in October. After that, an improvement of the indicator followed, although it stayed at rather low. Moreover, the consumer confidence indicator shows that households remain particularly cautious about their planned major purchases (+12m). A similar picture emerges from the survey of companies to what extent that insufficient demand hampers their activity: it is not the demand for commonly consumed goods or services but rather for consumer durables that seems to be an increasing factor hampering activity since the summer of 2021 (see Figure B2).

Thus, it seems very likely that the still high level of pessimism among consumers mainly affects willingness to buy consumer durables (such as furniture or a washing machine). This contrasts with the theoretical reasoning, mentioned earlier in this article, that high inflation may induce consumers to push forward the purchase of durable goods (intertemporal subsitution).

Recently, we have also seen a gradual negative turn in the labour market, which could negatively impact household consumption. For instance, the year-on-year change in the number of jobseekers since September 2022 turned positive again (see Figure B3). The deterioration will not translate into a sharp rise in unemployment in our view, though. Companies will hoard labour more than in previous similar cyclical phases2. Indeed, there are factors driving the hoarding behaviour associated with the labour market tightness that companies faced soon again after the pandemic. First, the impact of the pandemic on companies' financial health has generally been limited. This gives them some resilience in the current energy crisis and puts them in a better position to keep staff with them. Furthermore, the impending demographic contraction in labour supply implies that once economic growth picks up after the crisis, tightness is likely to continue with even greater intensity. Belgium's unemployment rate (harmonised Eurostat definition), which still remained low, will in our view rise slightly from 5.5% in November (last available figure) to 6.1% by the end of 2023.

1 See KBC Economic Opinion, "Consumer confidence not always a reliable predictor of consumer confidence", 20 September 2017.

2 See KBC Economic Opinion, "Labour hoarding in uncertain times", 13 October 2022.

1 See e.g. S. Georganas, P.J. Healy en N. Li (2014), "Frequency bias in consumers’ perceptions of inflation: an experimental study", European Economic Review, 67, p. 144–158.

2 See also KBC Economic Research Report, "Inflation shocks with real impact", 3 June 2022..

3 Zie S. Kremer, A. Bick en D. Nautz (2013), “Inflation and growth: new evidence from a dynamic panel threshold analysis”, Empirical Economics, 44, p. 861–878.