Emerging Markets Quarterly Digest: Q4 2021

Content table:

Read the publication below or click here to open the PDF.

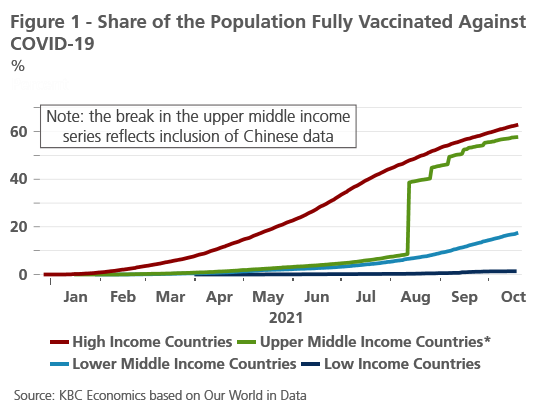

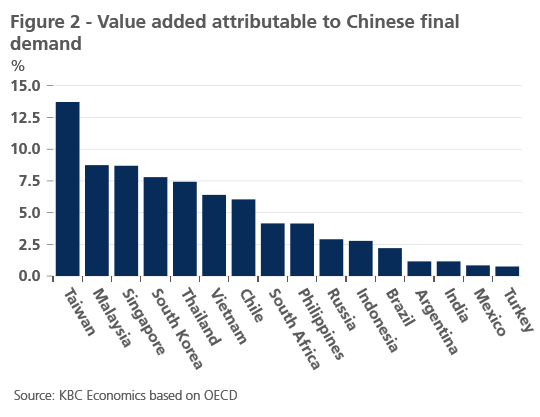

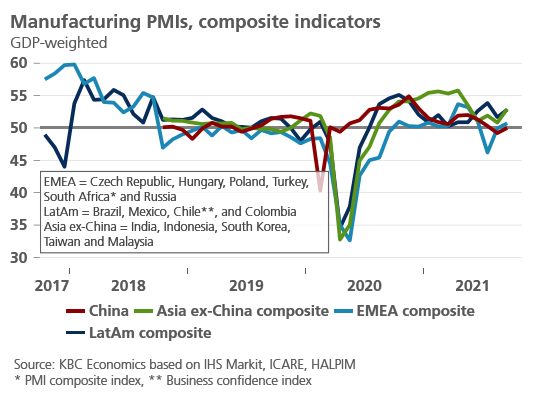

A persistent but slowing recovery

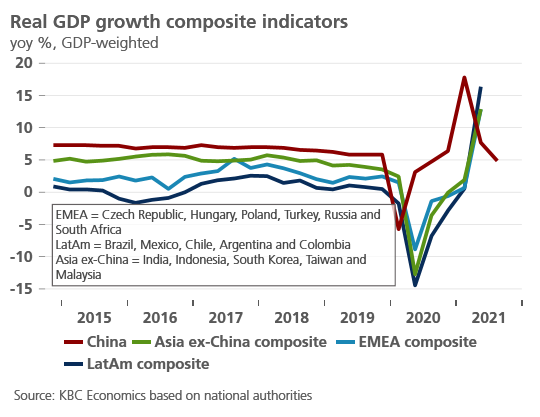

Heading into the last stretch of 2021, the global economic recovery continues but is on somewhat fragile footing for emerging markets. We noted back in May 2020 and many times since, that a number of factors, such as more limited policy space and external vulnerabilities, could exacerbate the economic fallout from the Covid crisis for emerging markets in comparison to advanced economies. Throughout 2021, this has become increasingly the case as the recoveries in emerging markets have faced a number of headwinds, including comparatively slower vaccination rollouts, new covid waves, longer-lasting lockdowns, and now, somewhat less favourable global macroeconomic conditions. With growth momentum likely past its peak in the US and European economies, China facing a more significant slowdown, and supply chain disruptions lingering for longer than expected, the external growth environment appears set to turn slightly less supportive for emerging markets.

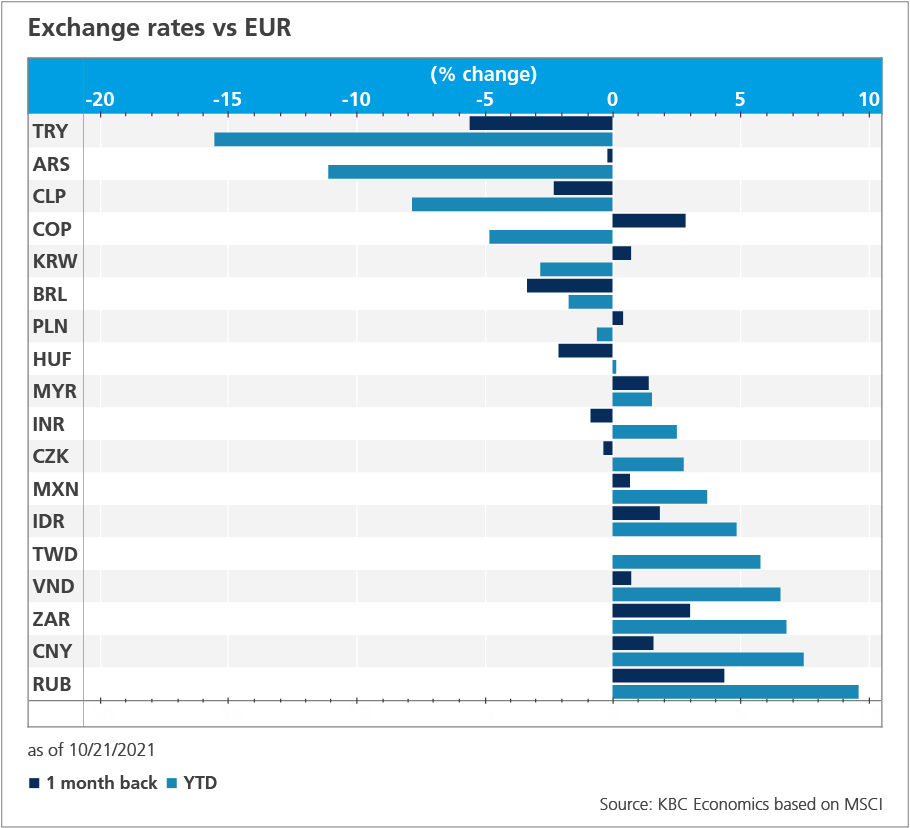

At the same time, global inflationary pressures remain high after rebounding from the lows reached in early 2020. While a significant portion of the inflationary pressures reflect base effects alongside economic normalisation, particularly with regard to energy prices, there have also been upward pressures stemming from food prices and from the supply-side shortages seen throughout global value chains. While we continue to see these price pressures as transitory, inflation is likely to remain elevated for somewhat longer and there are clear upside risks to the forecast. The recent further increase in energy prices (e.g. gas, coal and oil) will add to these inflationary pressures, though commodity exporting emerging markets are likely to see some benefit. Overall, however, the inflationary pressures are particularly concerning for emerging markets given differences in central bank credibility, the weight of food in price baskets, and capital outflow risks, all leading to a lower tolerance for inflation moving above target. And indeed, because of this, a number of smaller central banks are well into pre-emptive hiking cycles already, despite the still incomplete recovery.

Though there is broad agreement among markets and central banks that the currently higher inflation is transitory, the tide also seems to be turning for major central banks toward at least marginal tightening. The Fed, in particular, has signalled that some policy normalisation is on the horizon, first through tapering starting this year. Separately, the Fed’s ‘dot plot’ now suggests rate hikes could come as early as next year. In general, tighter global financial conditions present a headwind for emerging markets, and this is particularly the case now, as the economic recoveries in emerging markets lag behind the advanced economy recoveries.

Pockets of optimism

Though the landscape remains quite fragile and potentially turbulent for emerging markets, the global growth story has certainly not been derailed. Despite some growth downgrades, we expect the recovery in emerging markets to continue, only at a potentially slower pace. This recovery will be supported by continuing vaccination campaigns and the gradual reopening of economies, as well as by still elevated, albeit slowing, external demand.

On the Covid front, the Delta infection waves that spread through much of Asia during the third quarter are subsiding, and mobility statistics in the region are improving. In Latin America too, following a severe wave in the first and second quarters of 2021, weekly new cases have declined to levels not seen since the beginning of the pandemic. New confirmed cases are creeping up in some Central Eastern European economies (with Romania being a strong outlier to the upside), but for the most part, overall numbers are substantially below those seen during previous waves, and vaccination rates appear sufficient for the time being to keep hospitals from being overloaded and to keep new lockdown measures from being implemented.

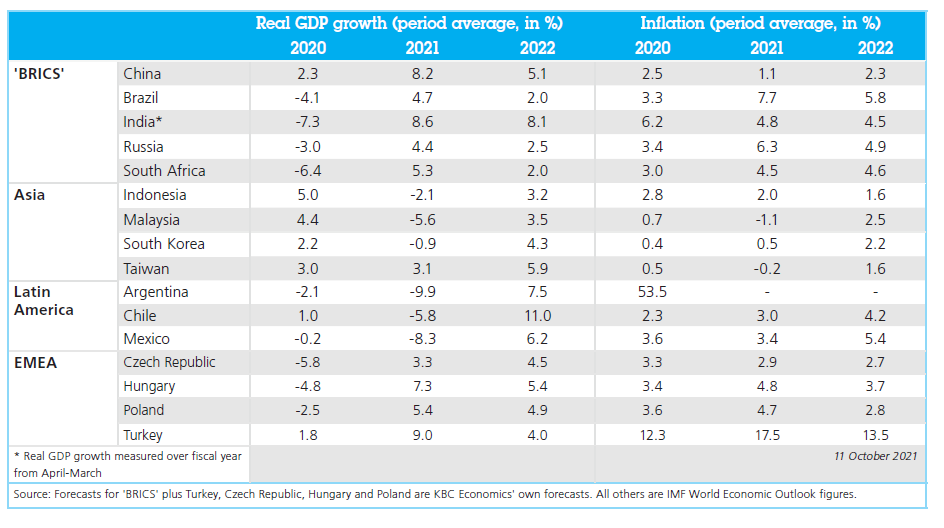

This point on vaccination applies to the other regions as well, with coverage in upper-middle-income countries nearly on par with that of high-income countries, and progress in lower-middle-income countries lagging behind but picking up pace since August (Figure 1).

For many emerging markets, there is still significant catch-up growth to be gained, especially on the services side. Ongoing vaccination campaigns should support the gradual reopening of economies, in turn supporting economic activity. It is important, however, to highlight the still very limited vaccination progress among low income countries. As long as global vaccination rates remain insufficiently low, the risk remains that new disruptive outbreaks, and potentially more worrisome variants, could further complicate the economic recovery.

Global energy crunch

Global energy prices have surged in recent weeks affecting coal, natural gas, crude oil and electricity prices. While there are idiosyncratic factors contributing to the developments in different regions, China, India, and Europe are all either dealing with or face the possibility of dealing with energy shortages in the current and coming quarters. Despite distinctive factors, such as decarbonisation policies in China (see below for details), the monsoon season in India, and supply issues between Russia and the EU, there are also a number of common threads connecting the global energy story. For example, high demand, sticky electricity prices versus rising coal and gas prices, and abnormal seasonal weather factors are playing a role in all cases. The higher energy prices and shortages are likely to have an important impact on the economic recovery in China and India and could also lead to new growth headwinds in Europe. It is important to note that this global energy price shock is expected to be temporary, with governments stepping in to alleviate the shortages. However, tighter energy markets could last through Q1 2021 and will likely add to currently elevated inflationary pressures.

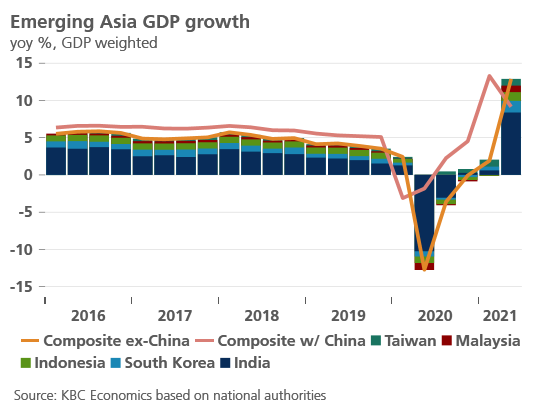

Emerging Asia

With the Q2 and Q3 Delta waves finally abating in much of emerging Asia, the main headwind to growth in the region so far this year appears to be finally easing. Though mobility statistics for the most part started to improve toward the end of the third quarter, Q3 GDP growth was likely still relatively weak for the region, and a stronger improvement in activity should be seen from the fourth quarter onward.

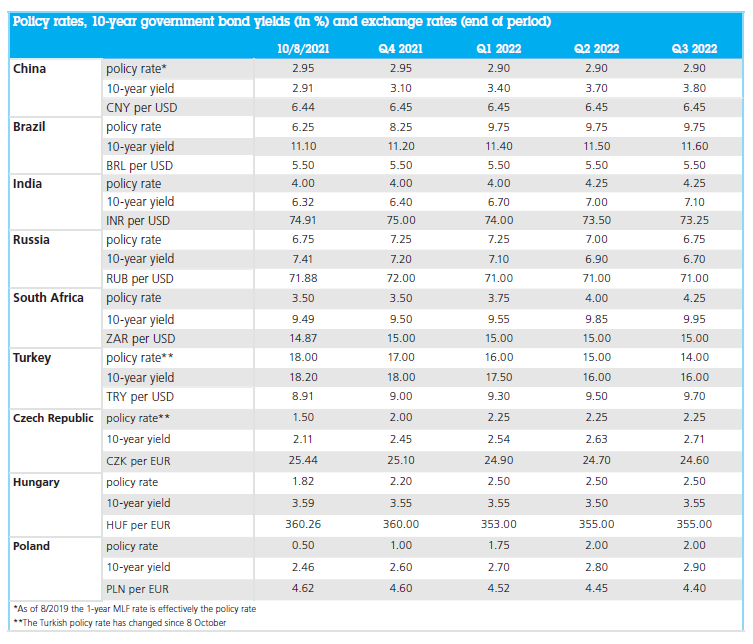

Of course, new headwinds to growth do appear to be popping up, mainly in the form of a stronger-than-expected slowdown in China. For a number of economies in the region, value added attributable to Chinese final demand is above 6% (Figure 2). But it is not only the final demand side of the equation that could hinder regional growth. Supply-side bottlenecks and disruptions have been a key challenge for the global economy this year, and developments in Asia have been at the centre of it. Covid-induced factory shutdowns and port closures in recent months may be easing, but the energy crisis in China is likely to significantly disrupt industrial output, putting new pressures on supply chains.

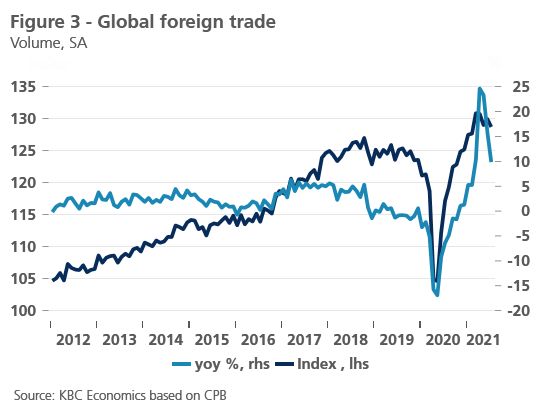

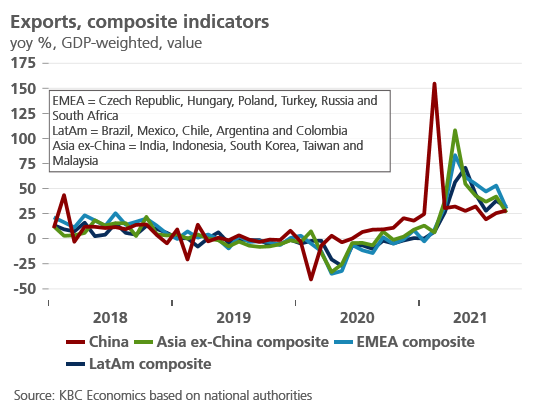

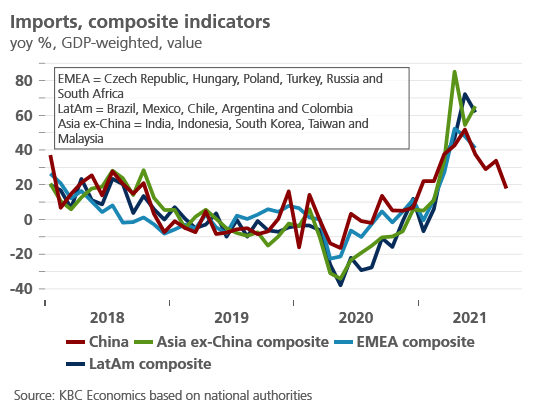

These supply-side disruptions, which began with the onset of the pandemic in early 2020 and have lasted well into the recovery, raise the question of whether global supply chains will structurally shift going forward. Indeed, even before the Covid crisis, escalating tariff measures imposed on imports between the US and China prompted such questions. It should be noted that there are demand pressures at play too, with global trade having been an important driver of the global recovery thus far. Momentum in global trade does appear to be slowing (Figure 3) and this could help alleviate dislocations that have, for example, led to surging shipping prices.

Aside from these short-term disruptions, it is also important to note that there are longer-term, structural factors that could affect supply chains. Digitalisation and automation are particularly important ones, especially in the context of the shortage in semiconductors since the end of 2020. While these dislocations partially reflect a faster-than-expected rebound in demand, for example in the auto industry, as well as a surge in demand for electronics throughout the pandemic, the ongoing trend toward digitalisation means a structurally higher demand for chips going forward (see KBC Opinions: Could a post-Covid world see a digital boost to productivity? and Chip shortage is a harbinger of the digital future). In line with this, we see many governments focusing on boosting investment in semi-conductors, with an underlying goal of protecting high-tech industries from future disruptions, whether those disruptions stem from shocks like a global pandemic or from shocks that are more geopolitical in nature.

The climate crisis is another structural challenge that will likely have a long-term impact on supply chains. As seen already this year, extreme weather events such as flooding can disrupt factory activity and output, leading to bottlenecks within value chains. The upstream links in supply chains are also vulnerable to swings in commodity prices as evidenced by recent energy shortages globally. As policy adjusts to incentivize the transition to a low-carbon economy, more such disruptions are possible. Finally, the effects that the climate crisis will have on regional labour forces (either through migration or adverse health impacts) may also lead to a shift in global supply chains away from more exposed regions. While the above factors are all long-term in nature, in the short term, we expect logjams in supply chains to abate in the coming quarters.

China

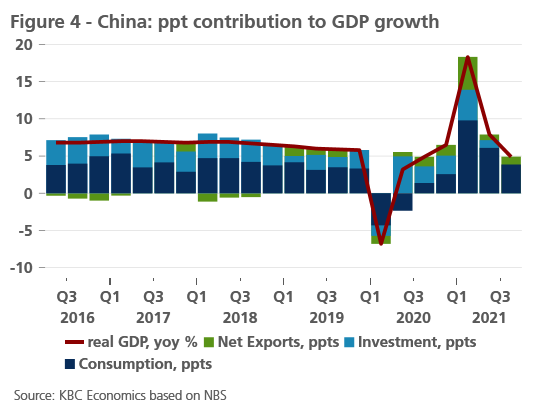

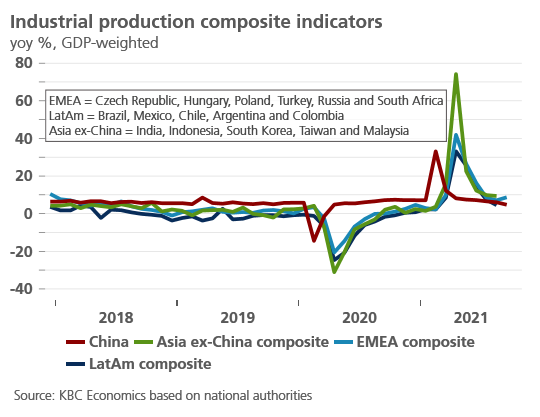

Chinese GDP growth continued to decelerate in Q3 to 4.9% yoy from 7.9% yoy the previous quarter. This reflected a strong deceleration in quarterly momentum from 1.2% qoq in Q2 to 0.2% qoq in Q3. While external demand held up well, consumption only modestly recovered after the most recent Covid wave, and investment weakened further, pulling down the year-over-year growth figure (Figure 4). This is consistent with what we see in industrial production figures (decelerating from 0.5% mom growth in June to 0.05% mom in September), retail sales figures (which contracted 0.23% mom in July but recovered to 0.3% mom growth in September) and export growth (which accelerated in both August (25.5% yoy) and September (28.1% yoy)).

The particularly weak industrial production data at the end of last quarter is partly indicative of the power shortages and planned outages that picked up steam in late September and have continued into October. The electricity shortages stem from several factors coalescing at once, including a reduction in coal production and electricity production due to China’s new emission efficiency targets, reduced coal imports due to geopolitical disputes, and spiking coal costs which, combined with capped electricity prices, have eaten into electricity producer’s profits. Given that China still derives roughly 60% of its electricity from coal, the result is that electricity production can’t keep pace with China’s still fairly elevated, albeit slowing, economic growth rate (particularly on the industrial side). Planned (as well as some unscheduled) outages will weigh significantly on industrial production in Q4 and impacted Q3 activity. Reduced production capabilities in China could add further fuel to the ongoing global supply chain disruptions. While the government is stepping in to improve flexibility around electricity production, the shortages could last until Q1 2022. Furthermore, the long-term nature of decarbonisation efforts means that this may not be the last we hear of energy market disruptions in China.

On top of these electricity shortages, China also faces possible headwinds in the real estate sector, especially as the Evergrande saga remains unresolved, and other highly-indebted property developers are reportedly running into liquidity problems as well. There has been growing financial stress stemming from the potential collapse or restructuring of Evergrande, China’s most indebted property developer saddled with liabilities estimated at USD 300 billion. This comes on the back of increased regulatory efforts to rein in an overleveraged housing market and economy, in part to mitigate risks to financial stability.

While there has been some clear market reaction within China, on the real economy side, the impacts are also starting to appear in the high-frequency data, with some downward pressure on house prices. Widespread turbulence across the sector could weigh further on economic activity in China, as fixed asset investment in real estate development amounts to 12% of Chinese GDP and a large fraction of household wealth is held in the form of real estate. There could also be spill overs to consumer confidence and the production of certain inputs such as steel and cement.

Given these headwinds, we have downgraded 2021 real GDP growth to 8.2% from 8.8% previously. Given overhang effects, and the possibility that electricity shortages last into Q1 2022, we have also downgraded 2022 real GDP growth to 5.1% from 5.4% previously.

While the above-mentioned headwinds have raised the risk of a more severe slowdown in China, it is important to note that the Chinese government still assigns a high importance to economic stability and will step in to counteract any significant downward pressure on the economy. Indeed, aside from the government stepping in to address the energy shortage, it is also increasingly likely that the PBoC will moderately ease policy conditions further in the coming months, likely through some combination of reducing the reserve ratio requirement, increasing liquidity operations, and potentially reducing the Medium-term Lending Facility interest rate. In this context, the limited convertibility of the Renminbi and the resulting incomplete integration of Chinese financial markets in the global financial system also help to reduce the risk of potential contagion to the global financial system should a financial stress event in China occur.

India

As the result of a severe Covid wave through much of April and May, India’s economic activity collapsed in the second quarter, with a contraction of 12.24% quarter-over-quarter. That wave has since come under control and mobility, consumer confidence, and business sentiment have all consequently rebounded. We therefore anticipate a strong recovery in growth in the third quarter as the economy opened back up. The pace of vaccination has also picked up since the beginning of July, with 50% of the population partially vaccinated and 20% fully vaccinated, which should put the recovery further on track.

New headwinds are forming, however. Much like China, India faces an energy crunch of its own, fuelled by higher coal prices. A number of India’s coal-fired power plants reportedly have only a few days of coal supplies, with the shortages being blamed partially on disruptive monsoon rains, partially on poor planning and partially on higher global coal prices. Though the power outages so far seem to be relatively contained, a wider-spread energy crisis would be a major disruption to India’s nascent recovery.

Like elsewhere, higher coal prices and higher electricity prices will temporarily add to inflationary pressure. The central bank (RBI) will likely continue to look through these price pressures. Indeed, inflation in India is currently trending down alongside food inflation since June. We therefore continue to expect the RBI to wait until the second half of 2022 to hike its policy rate.

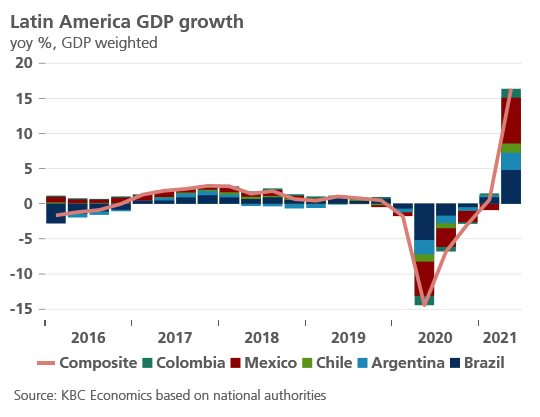

Latin America

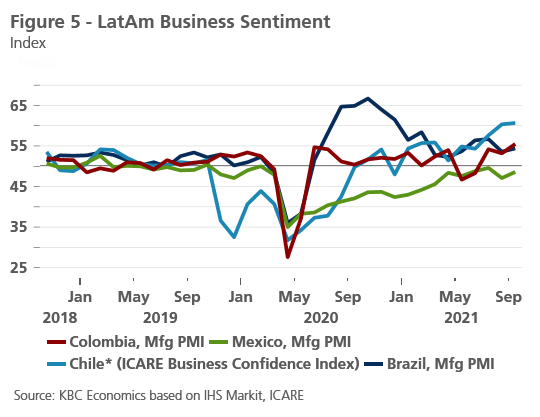

The outlook for Latin America started to brighten at the beginning of the third quarter and remains cautiously optimistic. The devastating Covid waves that swept much of the region in the first half of 2021 have come under control and mobility has improved to close to pre-pandemic levels. Business sentiment indicators have improved accordingly and are well above 50 (indicating expansion) in Chile, Colombia, and Brazil (Figure 5). While the recent increase in commodity prices adds to inflationary pressures, commodity exporters in the region can benefit from higher export revenues.

Higher inflation does present an important headwind to growth, however, as most central banks in the region have started to hike policy rates. The Central Bank of Brazil has been most aggressive in this respect, increasing the SELIC target rate from 2% in March 2021 to 6.25% as of the September meeting. With headline inflation breaching 10% yoy in September, and core inflation also surpassing the upper limit of the central bank’s target (5.25%) at 5.8% yoy, additional rate hikes are likely through Q1 2022. Aside from increases in energy-dependent transport prices, inflation in Brazil has also been driven by higher prices in housing, clothing, and personal expenses.

EMEA

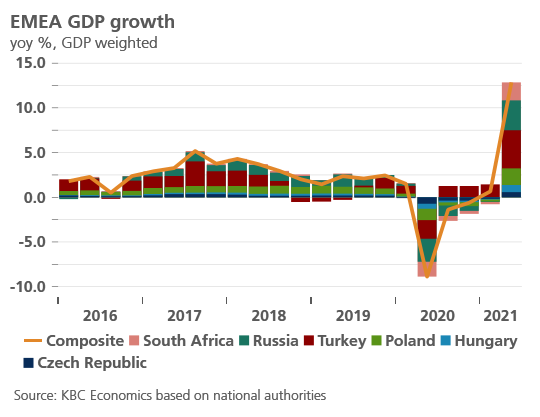

Central Eastern Europe

The waning of the pandemic and the gradual easing of containment measures in 2021 Q2 has boosted consumer and business confidence across economic sectors and lifted internal demand. However, it becomes increasingly clear that the recovery will not be as rapid as businesses had hoped. Consumer preferences may have changed, and fears of contagion and infection still persist in some (under-vaccinated) Central Eastern Europe (CEE) economies (e.g. Bulgaria). Moreover, on the supply side, growth seems to be increasingly hampered by global supply chain disruptions, shortages in the raw materials of specialized components, and bottlenecks in international transport. Longer-lasting supply chain disruptions may continue to weigh on growth and delay an early recovery.

Against this background of fragile recovery, Central European economies face strong increases in inflationary pressures. Headline inflation is well above 4% in the Czech Republic and well above 5% in Hungary and Poland, and seems clearly above the central banks’ tolerance thresholds. Increasing core inflation measures, moreover, point at underlying structural inflation. Looking forward, we do expect that inflationary pressures will persist this year – also on the back of the recent surge in gas, oil and coal prices – before eventually moderating.

These strong inflationary pressures – both in headline and core inflation – raise concerns over a potential entrenchment of higher inflation. Central banks in Hungary, the Czech Republic and, recently, Poland have acted in response to these pro-inflationary pressures. Both the Czech National Bank (CNB) and the National Bank of Poland (NBP) hiked aggressively during their last policy meetings. The CNB raised the policy rate by 75bps to 1.5% while the NBP fundamentally changed course with a surprise hike of 40bps to 0.5%. In both cases, central banks noted that a pro-active tightening was required to pre-empt or prevent negative feedback loops caused by second-round effects and keep inflation expectations well-anchored.

However, despite these similarities in the actual central bank decisions, the signals to the market differ markedly. The aggressive CNB rate hike constitutes primarily a frontloading of already planned rates hikes as the CNB already initiated its rate hike cycle in early summer. The upward July and August inflation surprises induced a more proactive CNB stance. In this context, the November forecasts will shed some light on the further rate cycle. With the November forecast in hand, we expect the CNB to deliver an additional 50bps rate hike by the end of this year (either in one or two steps) and then another 25bps hike up to 2.25% in February 2022. After that, we believe the CNB will opt for a “wait and see” period to assess the impact of relatively fast monetary tightening on the real economy and inflation. It should reach the 2.50% peak of the hiking cycle by the end of 2022. This scenario is already more than fully priced-in in the market rates. (For more details see: Perspectives Central and Eastern Europe)

South Africa

South Africa started 2021 with relatively resilient growth figures in both Q1 and Q2 (1.0% and 1.2% quarter-over-quarter, respectively). A sharp rise in Covid cases starting in May and peaking in June disrupted momentum, but mobility has since rebounded, and vaccination progress has picked up sharply since July (the share of the population fully vaccinated increased from less than 1% at the beginning of July to over 17% as of mid-October). Though Q3 was likely still weak, with GDP potentially contracting on a quarterly bases, the composite business sentiment indicator increased back to expansion territory (50.3) in September, and activity should recover in Q4.

Tables and Figures

Outlook emerging market economies