Emerging Markets Quarterly Digest: Q2 2023

Content table:

Read the publication below or click here to open the PDF.

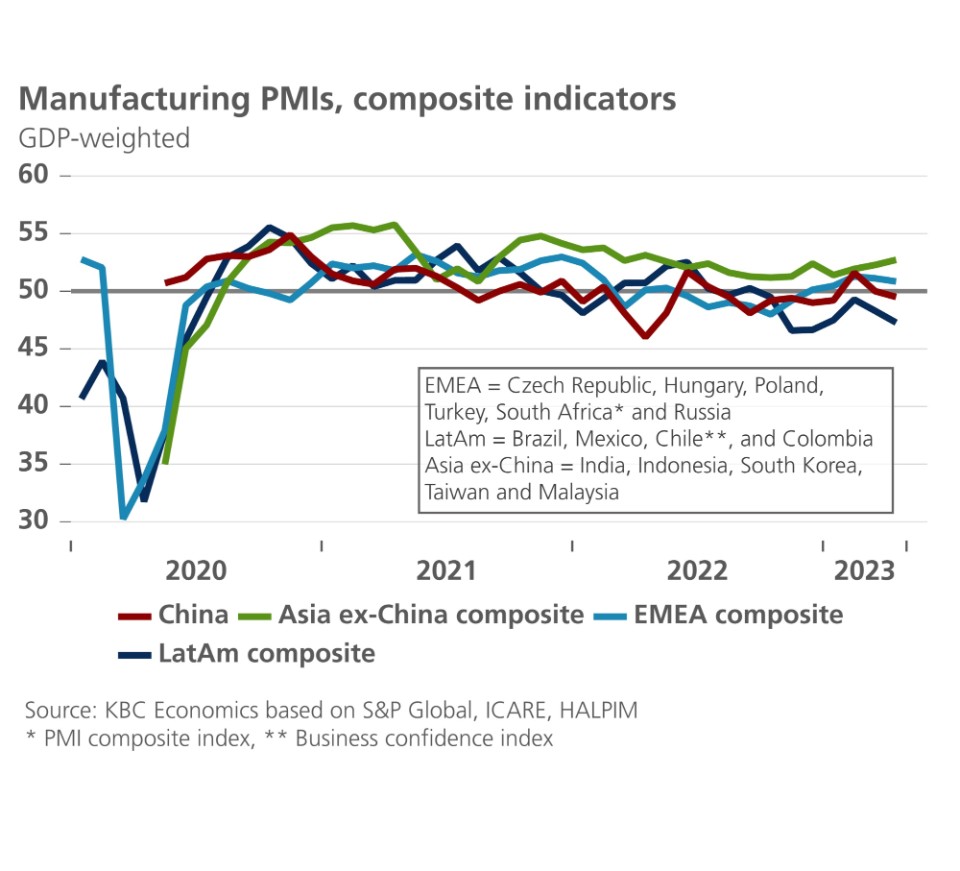

2022 was a challenging year for emerging markets economies. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, tighter financial conditions in response to high inflation, the stronger US dollar and China’s economic weakness due to its zero-COVID policy and property sector woes, all weighed on growth performances. The hardest hit regions were Eastern Europe and East Asia. Most Latin American countries weathered the storm somewhat better, thanks in part to an earlier, frontloaded, response to inflationary pressures by their central banks and strong trade links to the resilient US economy.

The momentum in the global growth environment has changed since our Q4 2022 publication. This made us cautiously more positive on the growth outlook for emerging markets. The most important driver of our revision of the outlook was the unexpected relaxation of the zero-Covid policy by the Chinese government end 2022. After an initial adjustment period following the re-opening of the Chinese economy, characterized by surging Covid-cases and disruptions to factories and supply chains, the gradual normalisation of economic activity will support Chinese GDP growth in 2023. Other factors that have improved the global outlook in the past months include efforts by the Chinese government to support its ailing property sector, gas price moderation in Europe because of mild weather conditions and the successful reduction of structural gas consumption, and the surprising resilience of the US economy. Turmoil in the (US) financial system and concerns about the strength of the Chinese recovery have clouded the outlook more recently, however.

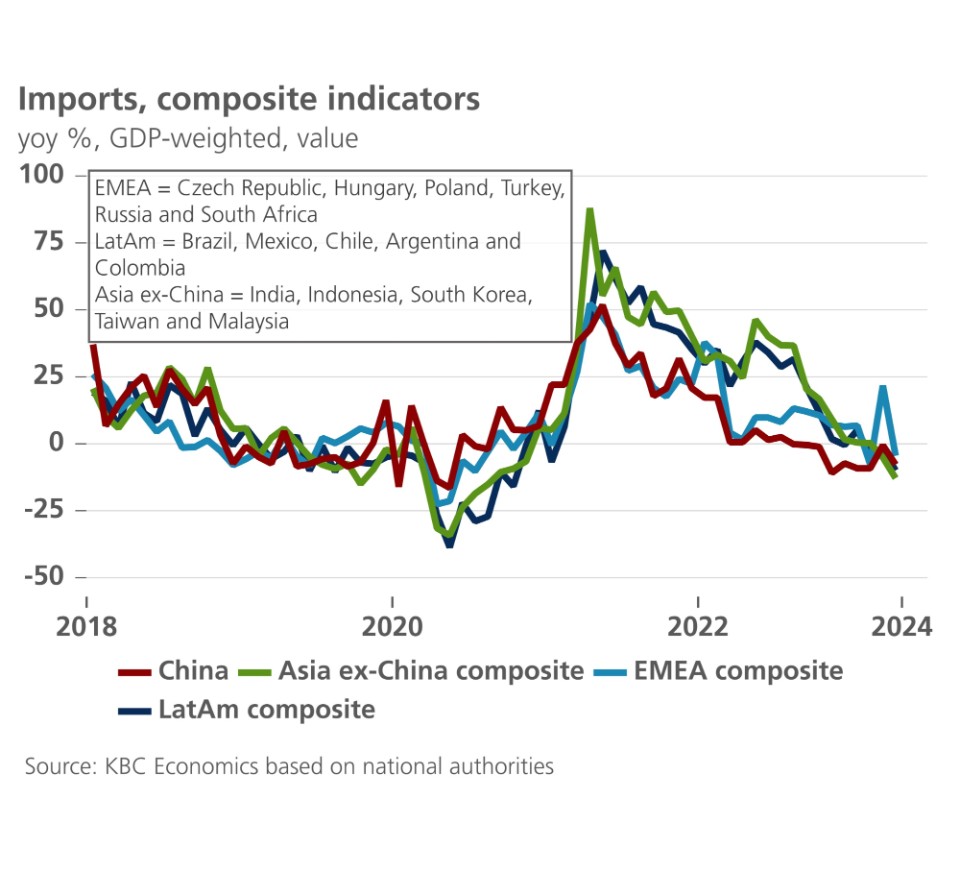

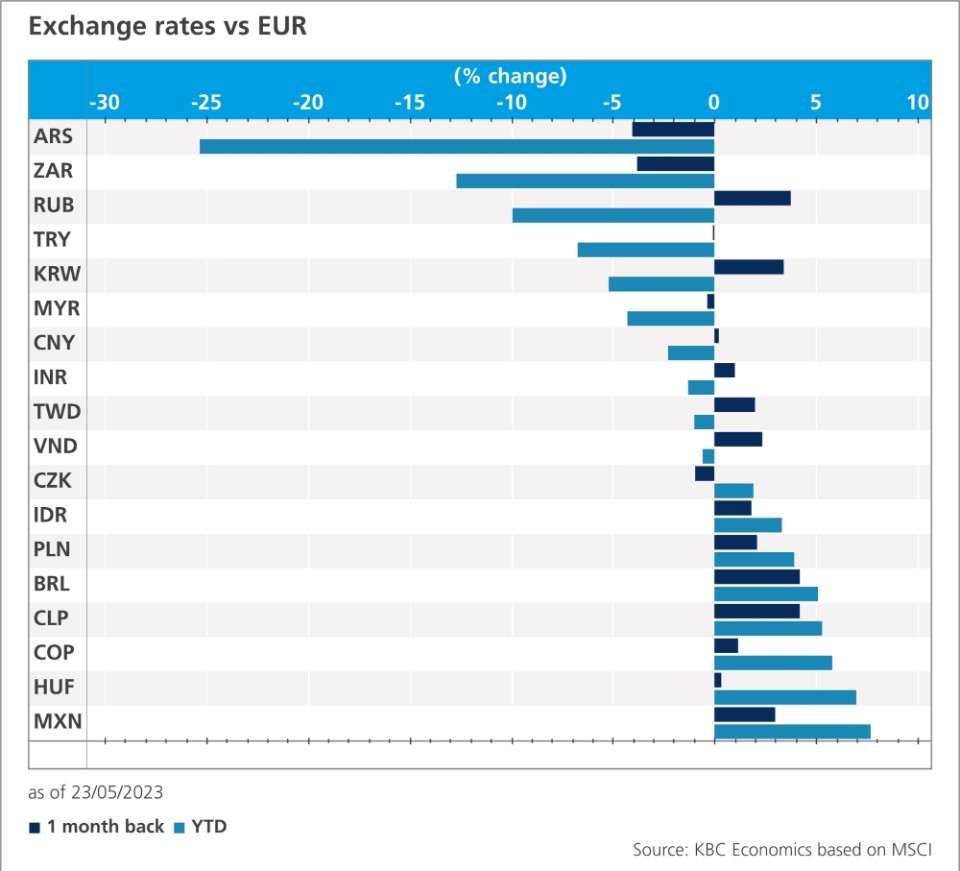

A second important change in 2023 is the ongoing deceleration of global inflation dynamics, especially in advanced economies (see figure 1). The deceleration is the result of lower prices for energy and non-energy commodities and fewer global supply chain disruptions. Cooling headline inflation numbers have paved the way for a slower pace and a lower end-point of rate hikes by major developed market central banks, including the US Federal Reserve. Rate hikes by the latter typically impact emerging markets by weakening the value of their currencies against the dollar, making it more expensive to service existing debt payments and triggering an outflow of capital investment. Especially countries with consistent trade deficits that are financed by dollar-denominated debt, like Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Turkey, can benefit from a weaker US tightening cycle. We now expect that the US Fed has reached the end of its rate hike cycle and that the current fed funds rate level will be maintained throughout 2023. There is significant uncertainty surrounding this scenario, however, as core inflation dynamics remain strong and labour market tightness continues. There is also an upward risk to inflation coming from the relaxing of Covid-policies in China, the world’s second largest economy and biggest consumer of commodities, but concerns on the total inflationary impact are still muted.

While still troubled by structural issues like high and/or rising debt levels, greater fiscal strains and the increasingly negative impact of demographics on potential growth, we see more confidence in emerging markets compared to last year. That is not to say that all emerging market are in the clear in the near future. A number of small, low-income economies are already in or seeking talks to restructure their debt, such as Sri Lanka, Zambia and Ghana, and regional or country-specific factors are weighing on the assets and the outlook of some larger emerging markets (such as the impact of years of unorthodox policy in Turkey or the looming risk of an escalation of the Russia-Ukraine war). While concerns about debt defaults in specific emerging markets persist, the risk of a systemic debt crisis is still contained at present.

Overall, risks are tilted to the downside. The most notable risks include the stalling of the Chinese recovery, a sharper slowdown in the Chinese property sector, stubbornly high core inflation which requires tighter monetary policy, renewed upheaval in the US financial sector that could lead to a global financial sector crisis and severe food and energy price pressures due to an escalation of the war in Ukraine or climate events.

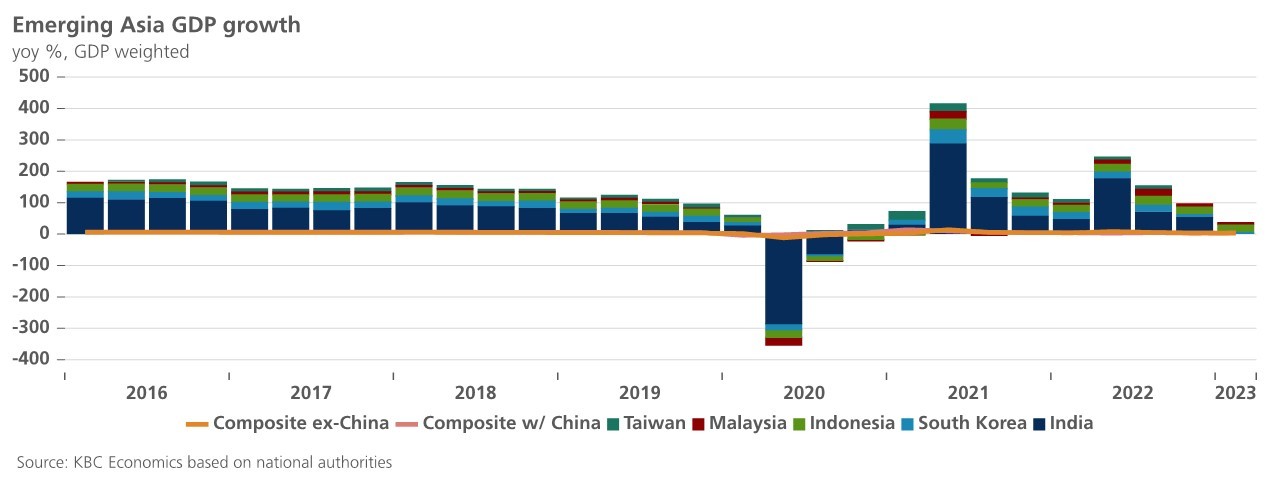

Emerging Asia

The reopening of the Chinese economy is expected to bring broad support to economic growth in emerging Asia in 2023. Especially countries with close ties to the Chinese economy (including through tourism) and commodity exporters will benefit from the activity normalisation in the region’s largest economy. Some of the growth push coming from the Chinese reopening will be offset by the global growth slowdown as economic activity in most Asian countries, including China and India, is highly dependent on external demand from advanced economies.

China

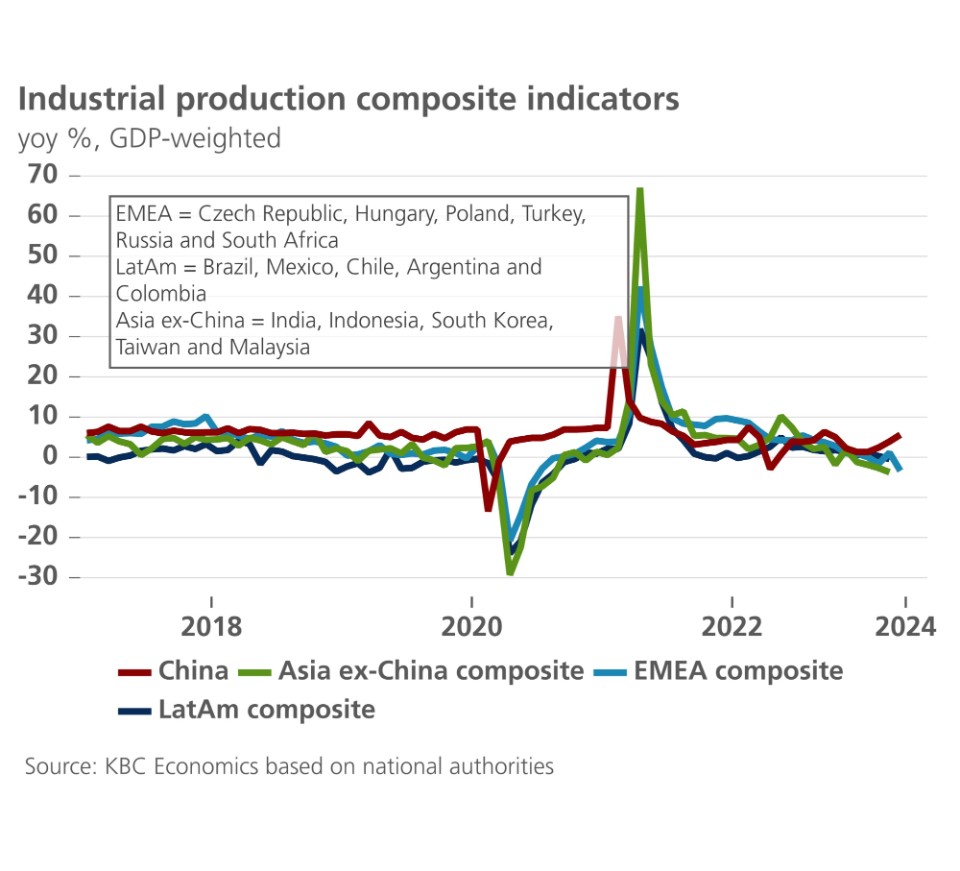

The combination of strict lockdowns in October and November and the chaotic abandoning of most containment measures in December after widespread protests resulted in a low real GDP growth rate of 0% quarter-on-quarter seasonally adjusted and 2.9% year-on-year in Q4 2022 (see figure 2). This brought the average annual growth figure for 2022 to 3%, a far cry from the government’s growth target of 5.5%.

At the beginning of Q1 2023, rampant covid-infections were still impacting factory output and private consumption. The feared mass infection waves washed over the country much quicker than expected and this helped boost economic activity as the quarter progressed. This resulted in a better than expected Q1 real GDP growth figure of 4.5% year-on-year. The strongest contribution to growth came from services, the sector that had been the most impacted by covid-containment measures. To reach the 5% growth target for 2023, economic activity needs to remain buoyant.

Looking ahead, we expect further growth acceleration in the services sector on the back of strong performances of the forward-looking PMI components. The PMI data for the services sector have increased significantly since the beginning of 2023 and are still well into expansionary territory. The PMI data for the manufacturing sector paint a much bleaker picture. Some of the improvements that were seen in February reversed again in March and both the NBS and Caixin manufacturing indicators came in below 50 in April. We therefore expect more growth support from the services sector than from manufacturing in Q2.

For now, we are conservative but still optimistic with our real GDP growth figure of 5.4% for 2023. Downward revisions are possible going forward if the expected acceleration in (particularly domestic) economic activity does not (fully) materialise. The same goes for our monetary policy forecast. We see no further cuts to the medium-term lending facility rate in the short term but this could quickly change if growth weakens, especially as the low inflation figures (0.7% year-on-year headline and core CPI in March) leave ample room for monetary policy intervention. In our base scenario, we do expect PBoC liquidity management will seek to maintain current funding rates.

In the years to come, China is likely to return to its gradually declining structural growth path as population ageing, economic restructuring, high corporate and local government debt levels and rising geopolitical tensions continue to put pressure on potential growth. The recent surge in US-China trade tensions is of particular concern for Chinese growth in the longer term. In the medium term, however, the US and Chinese economies will remain closely intertwined.

India

India’s economy is on track to become the fastest growing large economy in the world in 2023. An impressive accomplishment as the global growth slowdown will impact the Indian economy more than other Asian markets. The US and the EU represent the primary export destination, while only about 5% (pre-covid data) of exports are destined for China. Other Asian emerging markets typically have an exposure to China via exports of more than 10%. The strength of the economy mainly results from strong domestic demand as both (government) gross fixed capital investment and private consumption, especially in the discretionary segment, were robust in 2022. As a consequence of Western sanctions against Russia, India was also able to buy more Russian commodities at discounted prices.

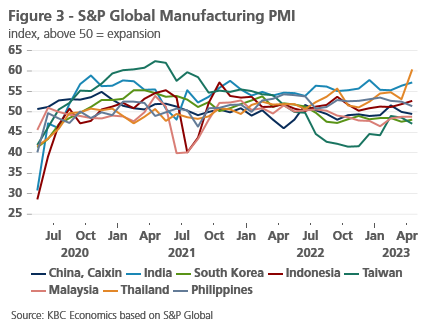

Looking forward, we see that high frequency indicators for the Indian economy are sending mixed signals. Consumer confidence about the current situation is improving but remains in the pessimistic zone while consumers’ expectations for the year ahead are stable and in optimistic territory. The manufacturing PMI is stable and still much higher than in most Asian emerging countries (figure 3). It is also still comfortably in expansionary territory, as is the services PMI. Goods exports, on the other hand, have slowed down visibly in recent months. Export weakness is expected to persist going forward as global growth weakens further. Consumer spending will continue to contribute to growth, albeit at a more moderate pace due to still elevated inflation pressures and higher borrowing rates. Investment growth will likely slow because of the withdrawal of pandemic-related fiscal support measures but the continued capex push by the government, as set out in the Union Budget 2023-2024, means government investment will continue to support growth.

We expect limited monetary policy support to growth going forward, although softening commodity prices and inflation should provide some relief to the RBI. This was already seen in the April meeting, when the RBI defied expectations of a 0.25% rate hike by deciding to keep its interest rate fixed at 6.5%.

Looking further ahead, India should benefit from growth-positive structural factors including its favourable demographics, its stable pro-business government and the ongoing supply chain readjustment of advanced economies away from China.

Export figures in both Mexico and Brazil held up well near the end of Q4 2022 thanks to the still strong growth performance of the US, which is an important trading partner for both countries. The expected slowdown of the US in 2023 will weigh on growth in the region going forward. The normalization of the Chinese economy could provide some counterbalance to US weakness on condition that the reopening brings about a material change in commodity prices. This is especially true for commodity-rich Brazil.

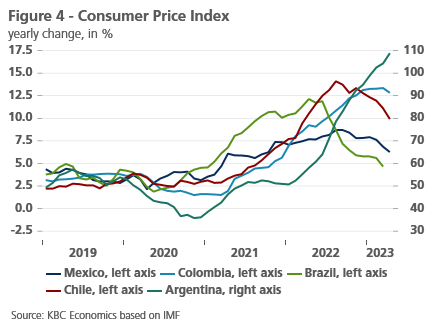

The inflation picture in Latin America looks very different depending on the individual country. Argentina is the absolute outlier with derailing inflation that moved above the 100% year-on-year threshold in April (figure 4). In an attempt to tame soaring inflation, the Central Bank of Argentina recently decided to raise its key interest rate by 6 pp to 97% in May 2023. Colombia also saw a continuous increase in inflation but its price growth rate (12.8% in April) is still much lower than in Argentina and seems to be stabilising of late. Price pressures in Chile, Mexico and Brazil are still elevated but clearly past their peaks as inflation is now on a downward path. The most outspoken decline was seen in Brazil, where inflation is again at levels last seen at the end of 2020 thanks to easing energy and commodity prices and a reduction in fuel taxes.

The manufacturing PMIs for Colombia and Mexico have been trending around the neutral level since the autumn of 2022 while Chile has seen its producer confidence indicator going down and situated well into negative territory for a year now. The weakness in producer confidence indicators in the region is in line with our expectations of a global (and especially US) growth slowdown. Investor confidence in Brazil in the months to come will likely to depend on the usual external factors, like commodity markets movement and Fed policy decisions, but also on Brazil’s fiscal position. The latter gained importance after leftist President Da Silva’s transition team pushed a 32 billion USD expansion of public spending through parliament in December 2022. To counterbalance their spending plans, the Brazilian government has unveiled an ambitious new fiscal framework (still to be approved) that combines a looser spending cap with primary budget target and a commitment to deliver a balanced primary budget in 2024.

Looking further into the future, we see relevant important longer term developments in Latin America: the trade deal between Chile and the EU and the start of talks on a common currency union between Brazil and Argentina. The first was concluded in December 2022 and hopes are that the deal will increase Chilean gross domestic product by 6% in the coming years. The deal will provide the EU with easier access to lithium, copper and other minerals vital to its renewable energy industry. In return, Chile will secure more favourable access for its exports, particularly food, and professional services. The other (less certain but) important development is the start of preparatory work on a common currency, dubbed ‘sur’, in January. If successful, the new currency would underpin the second-largest currency bloc in the world, after the EMU. Talks were initiated by Brazil and Argentina but other Latin American nations will be invited to join. The aim of the common currency would be to strengthen regional trade and to reduce reliance on the US dollar. Past attempts to set up a currency union between the two countries failed and many hurdles will have to be taken, including setting up a joint monetary policy. As a result, the process will be lengthy (several years) and the outcome remains highly uncertain.

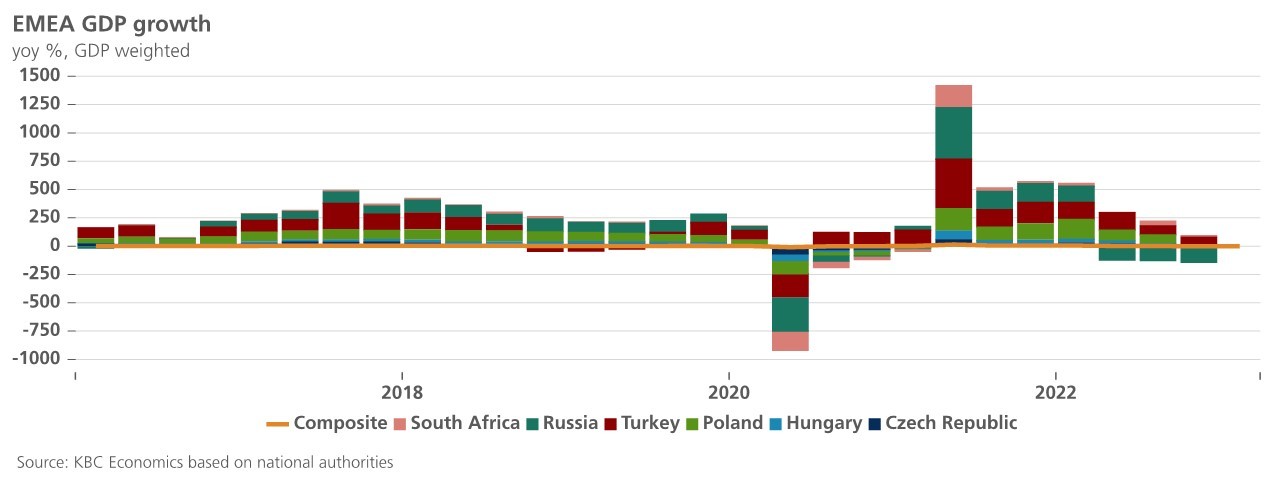

EMEA

Central Eastern Europe

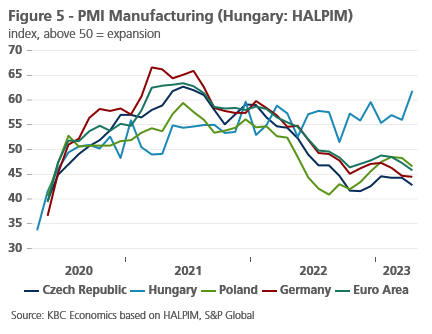

Falling energy prices and the reopening of the Chinese economy as well as the easing of supply chain disruption have lowered some of the risks to export oriented, energy-intensive CEE economies. This resulted in a bottoming out of the PMI manufacturing indicators at the end of 2022 (figure 5). But increased worries about the global trade environment and the Chinese rebound put again downward pressure on the PMI’s in 2023. The overall levels now imply that most CEE economies are headed for a growth slowdown this year.

Inflationary pressures persist in many of the CEE economies as core inflation has been the main driver of inflation over the last year. The more prominent role of core inflation in these economies is related to their large openness and the strong pass-through of energy and food price developments. Going forward, we can expect that also inflationary pressure of food will fade relatively soon, and the role of the main inflationary impulses could then be taken over by so far less visible factors: rapid wage growth and widening fiscal deficits. Even more so than for other emerging markets, inflation risks in the CEE region remain tilted to the upside because of the war in Ukraine. For a more detailed analysis see: Perspectives Central and Eastern Europe (kbc.com).

Turkey

No candidate secured a majority of the votes in the May presidential elections in Turkey. As a result, there will be a runoff on May 28th between the two leading candidates, current president Erdogan and rival Kilicdaroglu. Erdogan has the best odds as he secured the most votes in the first round. At stake are the economic future of the country, as unorthodox monetary policy under Erdogan has resulted in derailing inflation and a currency crisis (figure 6), and institutional reform, including a dismantling of the all-powerfull presidency and the restoration of central bank and judiciary independence. Opposition candidate Kilicdaroglu also wants to increase the independence of the press, crackdown on corruption and restore freedom of speech. While rather unlikely at this point, a win for Kilicdaroglu would also help bring back investment capital to Turkey. If president Erdogan succeeds in winning another term, some very moderate monetary policy tightening could still be in the cards as the current monetary policy is deemed highly unsustainable. Chances of a mild monetary tightening succeeding in bringing down inflation and supporting the currency remain slim however.

South Africa

South-Africa has seen an intensification of problems related the country’s power supply, which is almost exclusively provided by state electricity company Eskom. Local outages occurred for more than 200 days in 2022 and almost every day so far this year (22/05/2023). The underlying causes include breakdowns at ageing coal power stations, corruption and a lack of funds for proper maintenance. Business are now increasingly setting up their own independent power supply units since the government cut red tape that protected the Eskom power monopoly. This will help them operate in the future but is taking capital away from investment projects and employment and thus limiting current and future growth potential.

The disruptive nature of the outages is putting pressure on the government and the growth outlook. We expect outages (or load-shedding as they call it) to weigh on growth in 2023, bringing the real GDP growth figure to 0.4%. Against the backdrop of persistently high headline inflation (7.2% year-on-year in March), the South African central bank decided in its March meeting to raise the repurchase rate by 50 basis points to 7.75%. The repurchase rate is expected to stay at this level for the remainder of 2023.

Claims by the US that South Africa is supplying arms to Russia sparked unrest on financial markets recently as this ensuing diplomatic crisis could jeopardise trade with the US and other Western countries. South African businesses are especially concerned about losing the country’s participation in the African Growth and Opportunity Act, a US law that grants duty-free terms to specific nations. The stakes are high as the US constitutes an important trading partner, while Russia is only a minor export destination. South Africa is officially a non-aligned country in the conflict between the West and Russia but its position has been questioned repeatedly since the start of the war in Ukraine. Close financial ties between the country’s governing party, the ANC, and Russia are expected to be behind the government’s flirtation with Moscow.

Tables and Figures

Outlook emerging market economies

Note: forecasts are those prevailing on 8 May 2023

| Real GDP growth (period average, in %) | Inflation (period average, in %) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | ||

| BRICS | China | 3.0 | 5.4 | 4.9 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.3 |

| Brazil | 2.9 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 9.3 | 5.2 | 4.3 | |

| India* | 6.9 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 5.3 | 4.7 | |

| Russia | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| South Africa | 2.0 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 7.0 | 5.9 | 4.6 | |

| Asia | Indonesia | 5.3 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 3.0 |

| Malaysia | 8.7 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 3.4 | 2.9 | 3.1 | |

| South Korea | 2.6 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 5.1 | 3.5 | 2.3 | |

| Taiwan | 2.5 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 1.7 | |

| Latin America | Argentina | 5.2 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 72.4 | 98.6 | 60.1 |

| Chile | 2.4 | -1.0 | 1.9 | 11.6 | 7.9 | 4.0 | |

| Mexico | 3.1 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 7.9 | 6.3 | 3.9 | |

| EMEA | Czech Republic | 2.5 | 0.3 | 2.6 | 14.8 | 12.3 | 2.4 |

| Hungary | 4.6 | 0.1 | 3.5 | 15.3 | 18.6 | 6.0 | |

| Poland | 5.4 | 1.4 | 4.4 | 13.2 | 11.7 | 3.5 | |

| Turkey | 5.6 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 72.3 | 44.3 | 29.1 | |

| * Real GDP growth measured over fiscal year from April-March | 8-May-23 | ||||||

| Source: Forecasts for 'BRICS' plus Turkey, Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland are KBC Economics' own forecasts. All others are IMF World Economic Outlook figures. | |||||||

| Policy rates, 10-year government bond yields (in %) and exchange rates (end of period) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 08/05/2023 | Q2 2023 | Q3 2023 | Q4 2023 | Q1 2024 | ||

| China | policy rate* | 2.75 | 2.75 | 2.75 | 2.75 | 2.75 |

| 10-year yield | 2.75 | 3.10 | 3.05 | 3.00 | 2.95 | |

| CNY per USD | 6.92 | 6.89 | 6.86 | 6.83 | 6.80 | |

| Brazil | policy rate | 13.75 | 13.75 | 13.25 | 12.50 | 11.75 |

| 10-year yield | 12.21 | 12.70 | 12.65 | 12.60 | 12.55 | |

| BRL per USD | 4.95 | 4.97 | 4.95 | 4.92 | 4.90 | |

| India | policy rate | 6.50 | 6.50 | 6.50 | 6.50 | 6.25 |

| 10-year yield | 7.04 | 7.53 | 7.48 | 7.43 | 7.38 | |

| INR per USD | 81.77 | 81.42 | 81.06 | 80.70 | 80.35 | |

| Russia | policy rate | - | - | - | - | - |

| 10-year yield | - | - | - | - | - | |

| RUB per USD | - | - | - | - | - | |

| South Africa | policy rate | 7.75 | 7.75 | 7.75 | 7.75 | 7.50 |

| 10-year yield | 10.13 | 10.20 | 10.15 | 10.10 | 10.05 | |

| ZAR per USD | 18.34 | 18.32 | 18.24 | 18.16 | 18.08 | |

| Turkey | policy rate | 8.50 | 8.50 | 24.00 | 25.00 | 23.50 |

| 10-year yield | 12.71 | 12.00 | 25.00 | 18.00 | 18.00 | |

| TRY per USD | 19.50 | 20.57 | 21.83 | 22.27 | 22.41 | |

| Czech Republic | policy rate | 7.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 6.00 | 5.00 |

| 10-year yield | 4.58 | 4.63 | 4.59 | 4.53 | 4.49 | |

| CZK per EUR | 2.27 | 1.93 | 1.89 | 1.88 | 1.89 | |

| Hungary | policy rate* | 16.20 | 15.00 | 12.50 | 10.80 | 9.50 |

| 10-year yield | 7.85 | 8.10 | 7.80 | 7.30 | 7.10 | |

| HUF per EUR | 372.05 | 370.00 | 380.00 | 385.00 | 388.00 | |

| Poland | policy rate | 6.75 | 6.75 | 6.75 | 6.75 | 6.25 |

| 10-year yield | 5.84 | 5.70 | 5.50 | 5.40 | 5.20 | |

| PLN per EUR | 4.57 | 4.60 | 4.60 | 4.60 | 4.55 | |

| *China's policy rate refers to MLF rate, Hungary's policy rate refers to 3M BUBOR | ||||||

| There are currently no forecasts provided for Russia | ||||||