Emerging Markets Quarterly Digest: Q2 2022

Content table:

Read the publication below or click here to open the PDF.

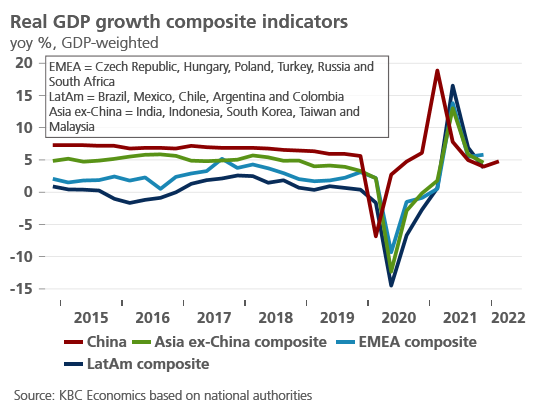

A complicated landscape

The global economic environment has become significantly more complicated for emerging markets in recent months for several reasons. First, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has sent energy and food prices soaring, exacerbating already high inflation. Second, supply chains are coming under renewed pressure given disruptions related to the Russia-Ukraine war and lockdowns in China. And third, global interest rates have risen sharply, with major central banks, and especially the Fed, signaling a more aggressive frontloading of monetary policy normalisation. Given emerging markets’ generally high sensitivity to food inflation, global trade, and Fed tightening cycles, the overall outlook therefore seems rather gloomy at first glance.

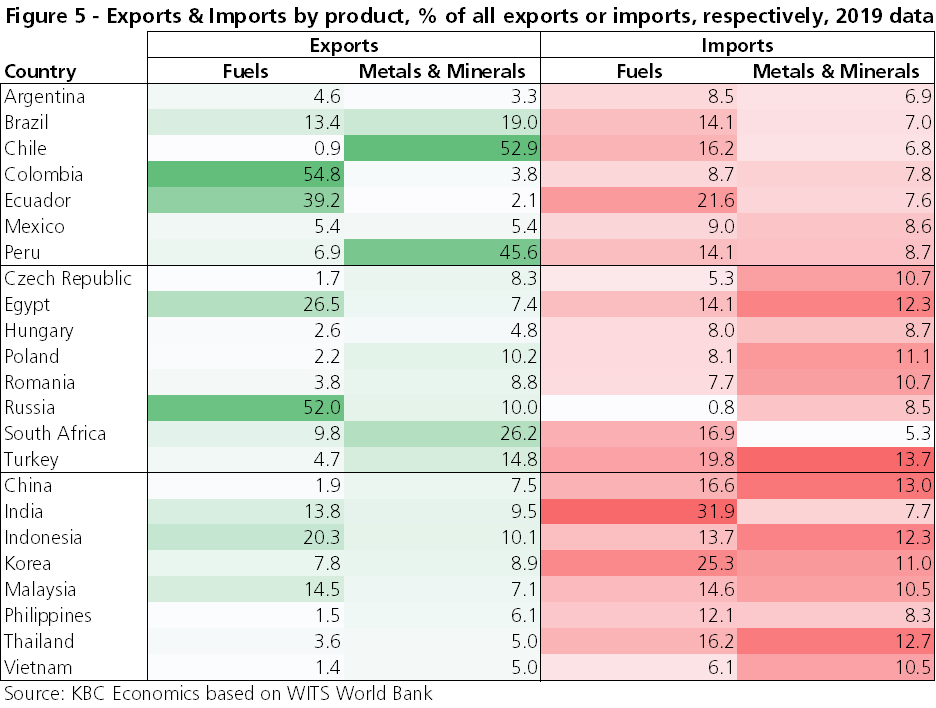

However, there are important distinctions to be made among emerging markets, such as the proximity to and importance of (energy) trade with Russia, whether a country is a commodity exporter or importer, and the extent of an economy’s external imbalances that make it vulnerable to rising US interest rates. European economies, for example, particularly those in Central Eastern Europe, are especially exposed given their reliance on Russia for energy imports. Meanwhile, after several years of lagging behind, emerging economies in Latin America may be better placed given the importance of commodities (fuels, metals, and minerals) within their export mix. While commodity exports also make up a large share of total exports for some economies in emerging Asia, economies in the region also tend to import a higher share of commodities relative to imports. This, together with the covid-related disruptions in China, muddies the outlook somewhat for the region in the coming months.

An energy supply shock

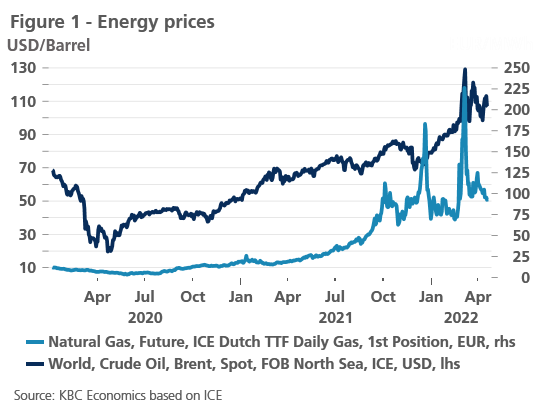

The immediate global economic implications of the war in Ukraine can be seen in the reaction in commodity markets, particularly for energy and food prices. Brent crude and natural gas (Dutch TTF) prices have eased from the highs reached immediately after the invasion, but energy prices are still elevated, and the market remains extremely tight and volatile (Figure 1). Given the uncertainty presented by the war, energy prices are likely to remain elevated for several months (as also implied by futures prices), and KBC Economics expects Brent oil prices to end the year at 100 USD/barrel.

The increase in energy prices has important implications for emerging markets, most of which were already dealing with rising inflation before the war. Some emerging markets are more exposed than other, however. Central Eastern European economies, in particular, rely on Russia for the vast majority of their natural gas imports (100% in the case of the Czech Republic). While Russian gas (and oil) continues to be exported to Europe, the risk of a disruption persists, which would constitute a major supply shock for the region (for details on the EU’s dependency on Russian energy supplies, see the box in the KBC Economic Perspectives of April 2022).

Energy producers and particularly net exporters are more shielded from the volatility related to supply from Russia, and may even benefit from higher prices, all else equal. It is important to note that higher energy costs, even for energy-exporting economies, still represent a negative supply shock for certain sectors, and can therefore weigh on household consumption. At the macro-level, however, this headwind can be (partially or fully) offset by activity from the energy sector, and net energy exporters may be able to shore up their current account balance thanks to the price shock.

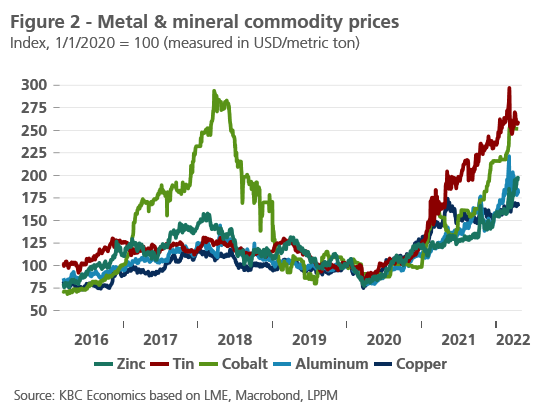

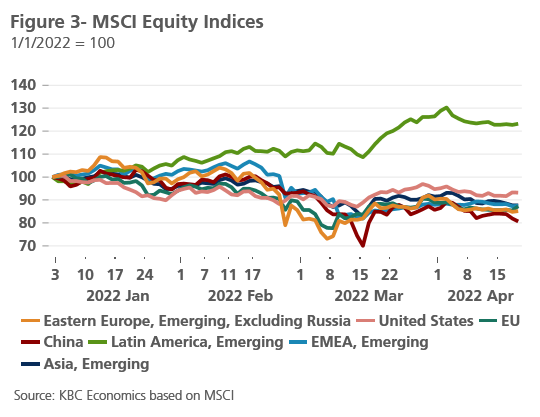

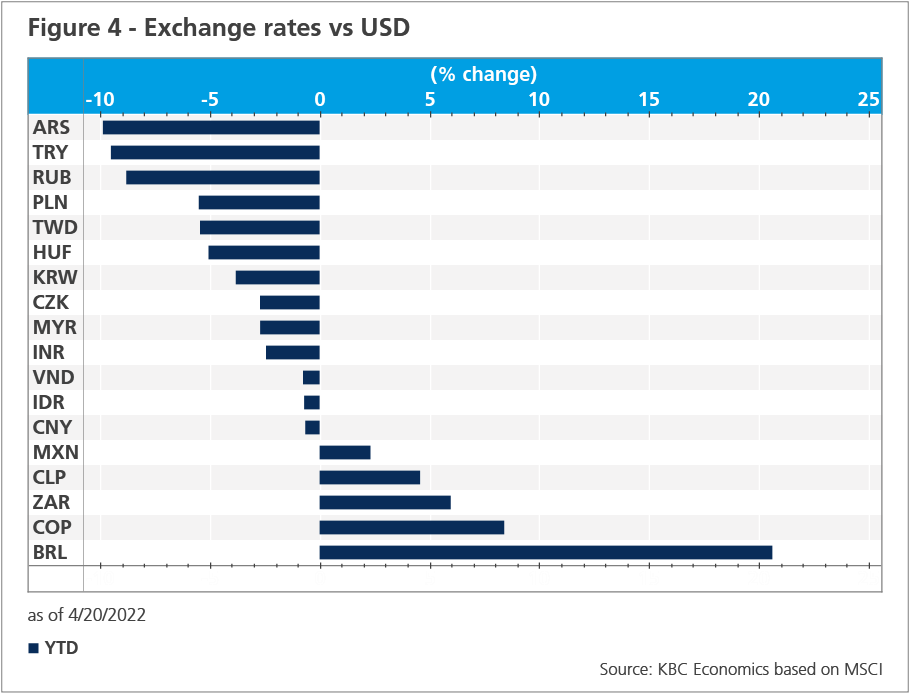

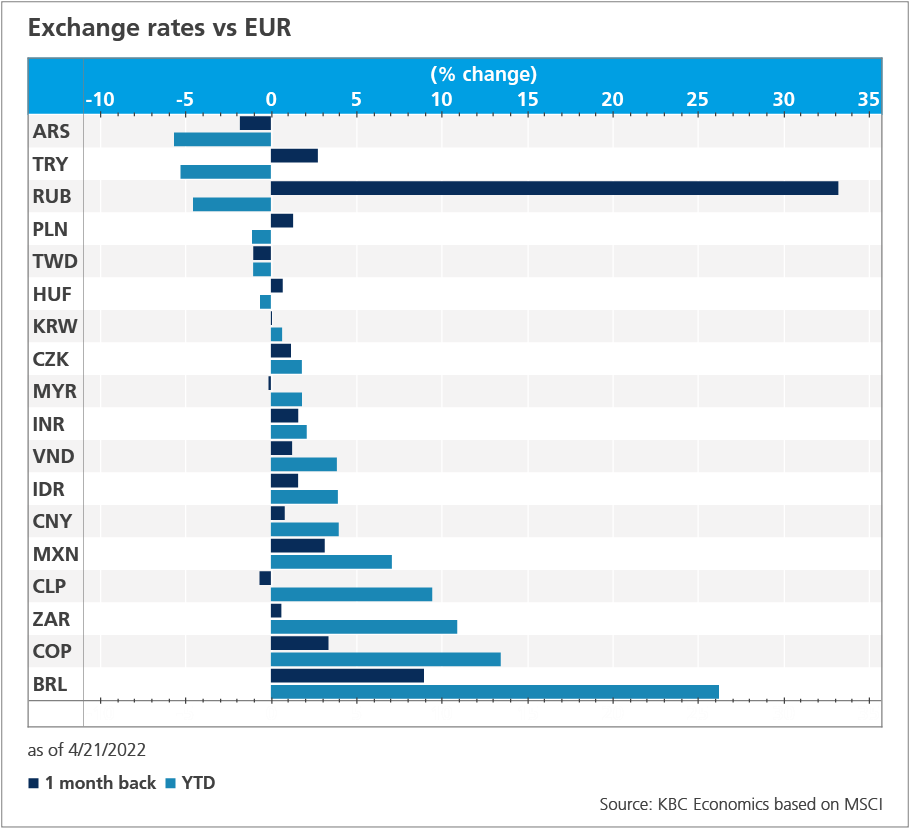

This, together with continued strength in other commodity prices (metals and minerals) since the middle of 2020 (figure 2), is one reason why emerging market assets (e.g., equities and currencies) in Latin America have generally outperformed those of CEE and emerging Asia economies since end-February or year-to-date (figure 3 and 4). The Brazilian real, Colombian peso, and Chilean peso, for example, stand out. Colombia is an example of a clear energy exporter; not only are net energy exports positive, but fuel exports account for 55% of total exports (figure 5). Brazil also exports more fuel products than it imports, making it a net exporter (though fuel imports as a percent of total imports are also elevated at 14%). But non-fuel commodities appear to be playing a role as well, particularly in the case of Brazil and Chile, with metal and mineral exports accounting for 19% and 53% of exports, respectively. The importance of metal and mineral exports is also an important reason for the outperformance of the South African rand so far this year (metals/minerals account for 26% of exports).

Food insecurity on the rise

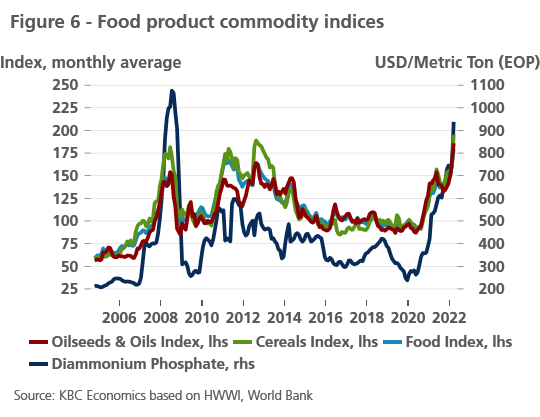

But energy products are not the only commodities affected by the war in Ukraine. Food prices have spiked as well, led by cereals (particularly wheat and corn) and vegetable oils (figure 6). The spike in wheat and corn prices is directly related to the fact that Ukraine and Russia are major exporters of the products. Supply routes through the Black Sea and out of Ukraine have been severely disrupted, and the war itself is most likely disrupting next season’s production. Higher input prices (i.e., energy and fertilizer costs) are also playing a role; the price per metric ton of diammonium phosphate, a key fertilizer used globally, increased 25% in March relative to a year earlier, primarily due to Russia being a major exporter.

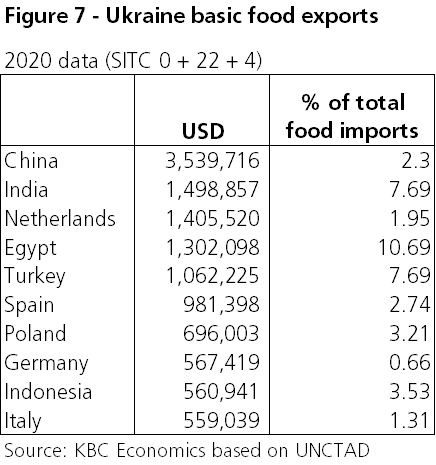

The spike in food prices will have global implications, but some countries will be hit worse than other. While the top importers of food from Ukraine on an absolute basis include China and number of European countries (the Netherlands, Spain, Poland, Germany, and Italy are in the top ten), for those economies, food imports from Ukraine account for only a small fraction of overall food imports (from 0.66% in Germany to 3.2% in Spain) (figure 7).

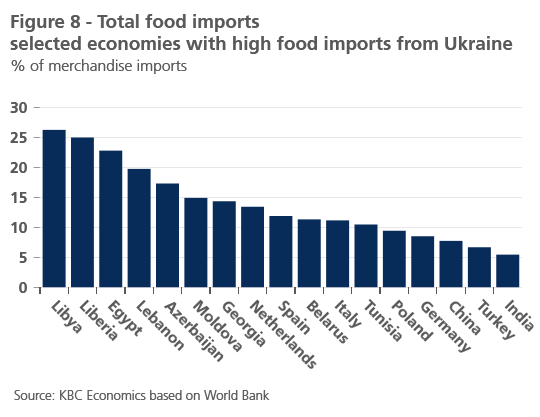

Furthermore, these countries are not especially dependent on food imports in general, with food imports as a share of total goods imports ranging from 7.7% in China to 13% in the Netherlands (the average for middle- and high-income countries is around 8%) (figure 8). Low-income economies tend rely more on food imports (averaging 17% of goods imports), with economies in Western and Central Africa, and the Middle East and North Africa, importing the most. From this respect, Egypt and Libya look particularly vulnerable, with 26% and 23% of total imports being food imports, respectively, and around 10% of their food imports coming from Ukraine.

While predictions of global food shortages may be premature at this stage (India reportedly has record wheat production this year), food prices are set to remain high in the short term. This not only puts some countries at risk of actual shortages, but it will also add to inflationary pressures, with an outsized impact on low-income economies and households. Indeed, the latest spike in February and March comes on top of already rising prices throughout much of 2020 and 2021. Similar to other supply disruptions that have become all-too familiar in recent years, the disruption to global food prices and supply will take time to unwind, as grain and other food needs to be shipped over different supply routes to make up for the shortfall from Russia and Ukraine.

Sharply higher interest rates, but no EM panic yet

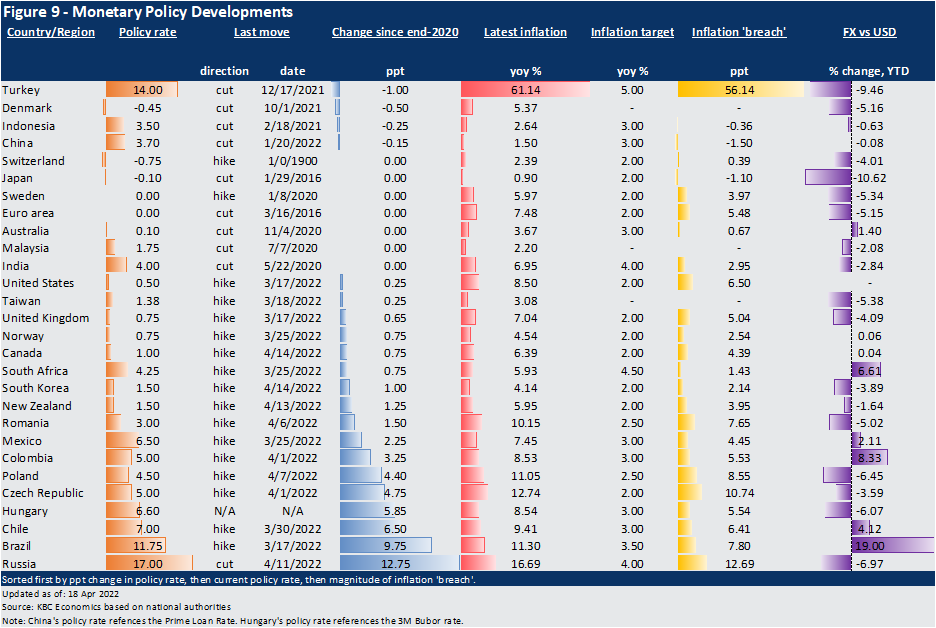

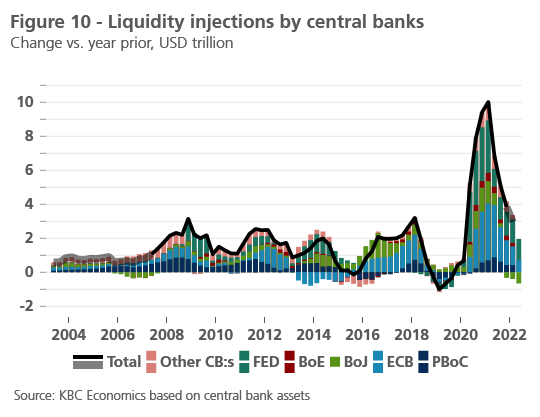

Another significant change in the landscape for emerging markets in recent weeks has been upward shift in benchmark interest rates—in particular those of US Treasuries. The increase in rates has come as the Fed (among other central banks) has signaled that its hiking cycle is likely to be more aggressive and frontloaded than previously envisaged in the face of spiking inflation pressures. Indeed, it has become increasingly clear over the past few months, that the period of ultra-easy monetary policy brought about by the pandemic is quickly coming to a close. Most major central banks have started hiking their policy rates already (figure 9), and liquidity injections by central banks (as measured by the change in assets) is moving sharply lower (figure 10).

Monetary policy tightening by advanced economy central banks often translates into turbulent times for emerging markets, potentially marked by FX volatility and capital outflows. So far, however, the repricing of market expectations for Fed policy tightening hasn’t resulted in a sharp downward repricing of major emerging market assets. Certain currencies have depreciated against the USD since the start of the year, but this has partially reflected proximity to the Russia-Ukraine war, as well as covid-related developments in Asia.

Indeed, many of the emerging markets with more substantial external vulnerabilities, including Chile, Colombia, Brazil and South Africa, have actually seen their currencies appreciate versus the US dollar since the start of the year. This, in part, reflects the impact of higher commodity prices as discussed above.

But another reason emerging market assets, including those in central Europe and elsewhere, have held up well in recent weeks is because central banks in those economies reacted early and aggressively to rising inflation pressures. Indeed, the EM tightening cycle started already last year, with Brazil’s central bank leading the way, raising its policy rate 9.75 percentage points since March 2021. This does not mean that emerging markets are out of the woods just yet, however. Some turbulence could still be on the horizon as markets digest the implications of the Fed’s policy rate hikes and imminent balance-sheet run-off. The recent announcement that Sri Lanka will not be servicing external debt payments as the country prioritizes using FX reserves to finance essential imports (such as food and fuel), is one such example of how the current global environment can cause difficulties for emerging markets.

Emerging Asia

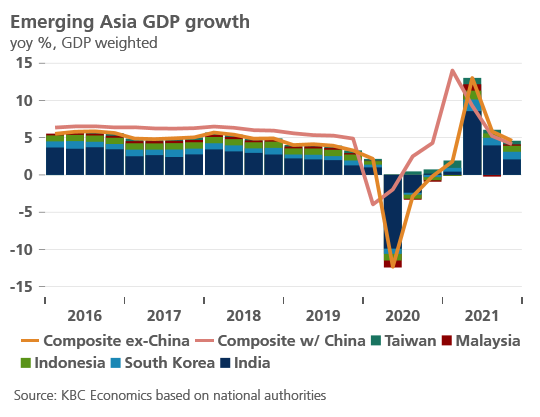

Covid catches up with China

China’s strict zero-covid policy has collided with the highly transmissible Omicron variant, leading to a deterioration in the outlook for Chinese GDP growth since early March. The government responded to a surge in cases by implementing strict lockdowns in a number of cities, most notably in Shanghai. These lockdowns have disrupted economic activity on both the production and consumption side as factories and businesses have been shut or subject to severe restrictions (e.g., the “closed-loop” system for workers) and residents have been confined to their homes. The lockdowns are also putting further pressure on global supply chains via delays at the port of Shanghai and other disruptions to shipping logistics within China (due to the closure of factories and warehouses, limited trucking availability, and the closure of exit/entry points for certain cities).

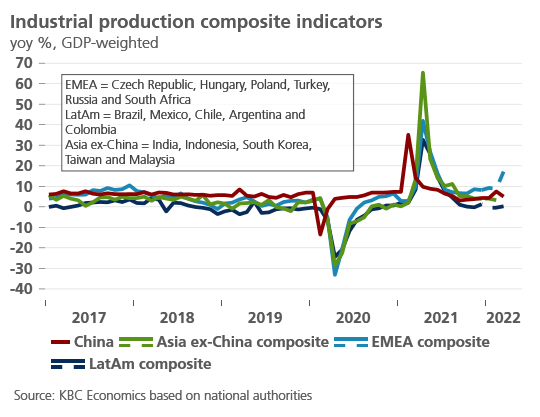

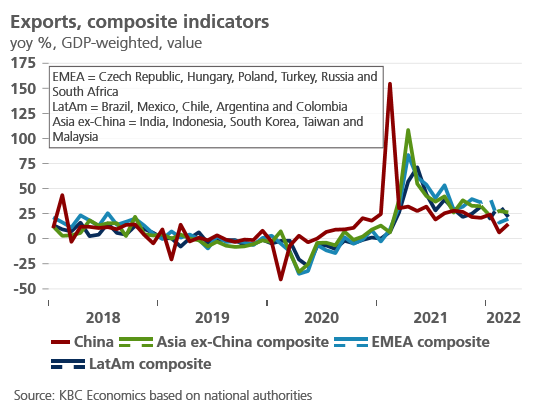

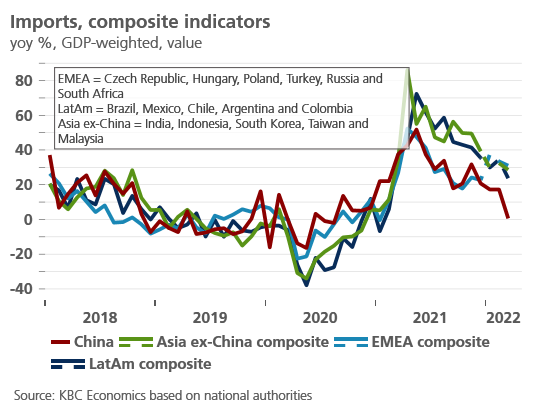

The impact of the lockdowns is evident in some of the more recent economic data, though GDP for Q1 held up well overall at 4.8% year-over-year (1.3% quarter-over-quarter). This in part reflected especially strong industrial output in February (7.5% year-over-year) before the impact of the lockdowns began. This helped offset a sharp drop in consumption and particularly the services sector in March; retail trade contracted 1.9% month-over-month, and the services business sentiment survey (Markit PMI) fell from 50.1 to 42.0, indicating a strong contraction. The decline in consumption could also be seen in import data for March, which contracted 0.1% year-over-year, down from a 15.5% year-over-year increase the month prior. Given the extension of lockdowns into April, and reports that the lockdowns are leading to production and shipping disruptions, GDP in the second quarter will likely show the effects, with somewhat weaker growth than in the first quarter. Of course, much of this depends on China’s covid policy going forward (as lockdown measures are slowly eased in Shanghai and elsewhere, uncertainty lingers as to how the authorities will deal with future outbreaks).

Policy will also play an important role in determining how China’s economy emerges from the current lockdown period. Policymakers have announced various measures to offset the domestic impact of the lockdowns, such as tax relief for small businesses, local government bond issuance to support infrastructure, and further (yet still limited) monetary policy support. The PBoC cut the Reserve Requirement Ratio for large banks from 10% to 9.75% but kept the prime loan rate (which is linked to the medium-term lending facility rate) steady in April. However, further interest rate cuts could be on the table if activity data after April remains especially weak. With a relatively limited policy response so far, and problems in the real estate sector still presenting a headwind to growth (prices declined again in March by 0.1% month-over-month in the primary market and 0.2% month-over-month in the secondary market), it will be difficult to manufacture a swift rebound in activity going forward. It therefore becomes even more difficult for the authorities to reach the 5.5% GDP growth target this year, and we have downgraded our growth outlook to 4.8% for 2022 from 5.0% previously.

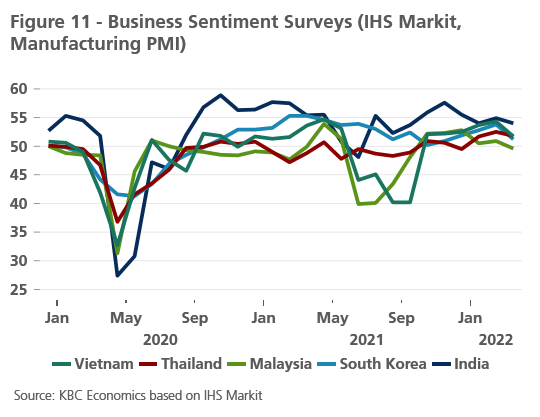

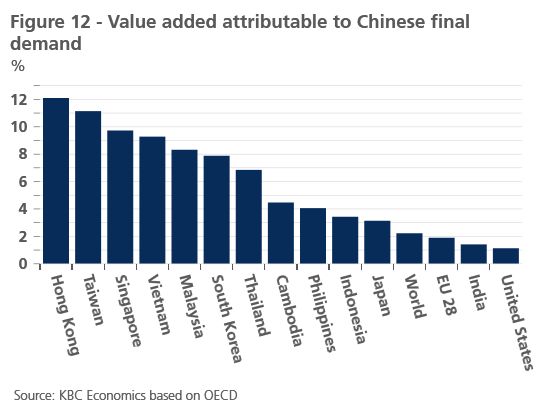

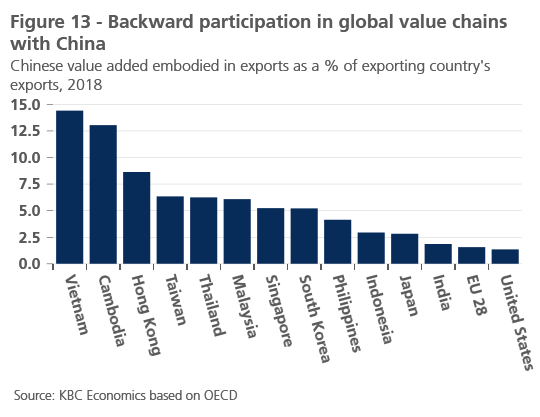

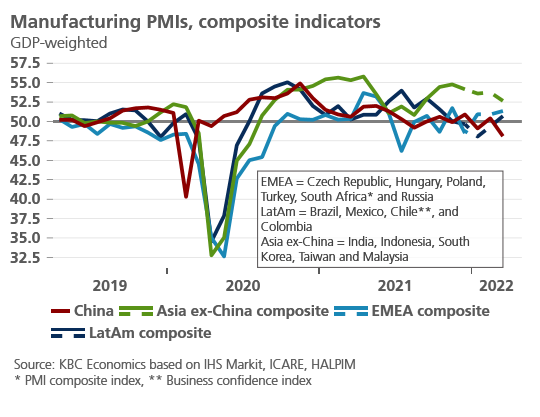

The headwinds to Chinese growth this year will put pressure on the region as a whole. High frequency data held up well through most of Q1 2022, but PMIs for many economies in the region edged down in March (figure 11) while export growth continues to decelerate from elevated levels. The weaker consumer spending in China (which translated into weaker imports in March) will weigh on economies that derive a higher share of value added from Chinese final demand (figure 12). There will also likely be spillover effects for those economies whose exports are highly embedded with value added from China, i.e., they are downstream from Chinese production, and therefore likely to be affected by disruptions stemming from the lockdowns. According to OECD data, this is particularly the case for Vietnam, Cambodia, and Hong Kong (figure 13).

India

The Indian economy finds itself in an interesting middle ground at the current juncture. High frequency data suggest activity held up well at the start of the year, with industrial production growing 1.7% year-over-year in February, supported by mining activity, and consumer confidence jumping from 64.4 in February to 71.7 in March.

As an important commodity producer (including of petroleum products but also wheat), India is somewhat shielded from developments in Ukraine. At the same time, however, inflation in India, like elsewhere, has been surprising to the upside in recent months, driven by higher food prices. The Reserve Bank of India, which has not yet started its hiking cycle but is expected to do so this quarter, may find itself leaning toward more front-loaded policy tightening, which would weigh on the recovery. We forecast FY 2022 growth at 7.3% – down from an estimated 8.9% in FY 2021 – with risks tilted to the downside.

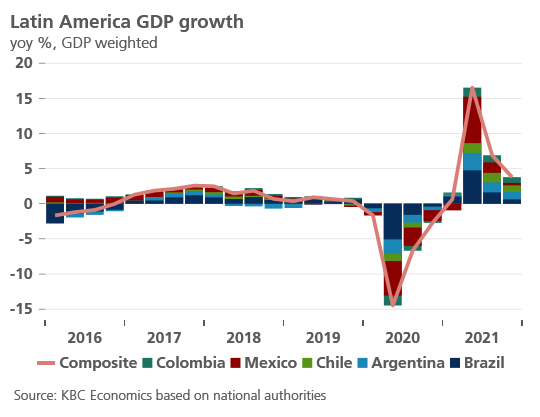

Latin America

Emerging market assets in Latin America have been the clear outperformer in recent weeks, with equity markets up 24% since the start of the year. This reflects the position of many economies in the region as commodity exporters of both fuels and minerals/metals, as well as their less direct exposure to the war in Ukraine or the lockdowns in China, and it is a notable divergence from trends seen over the past several years. It is also remarkable in light of the more extensive external imbalances in the region – such as current account deficits, wider fiscal deficits, and sizable external debt ratios (estimated by the IMF to be 52% of GDP in 2021, compared to a global average for emerging and developing markets of 31%) – which tend to make an economy more vulnerable to rising global interest rates.

As such, it is worth keeping in mind that while the region may be better positioned than other EM peers, there are still important risks to the growth outlook in the region. Sentiment data is mixed, with the manufacturing PMI improving in Brazil in March (to 52.2), remaining roughly steady in Colombia (at 52.1) and improving in Mexico (but to a still contractionary 49.2). Meanwhile, inflation continues to surprise to the upside in the region, particularly in Brazil (11.3% year-over-year in March). Hence, while the energy price shock might generate positive spillovers for certain commodity producers, it still constitutes a negative shock for household consumption. Furthermore, despite significant tightening already, the central bank of Brazil is expected to implement further policy rate hikes in the current quarter, bringing the SELIC target rate from 11.75% to 13.25%. We therefore forecast still rather modest growth of only 0.8% in 2022.

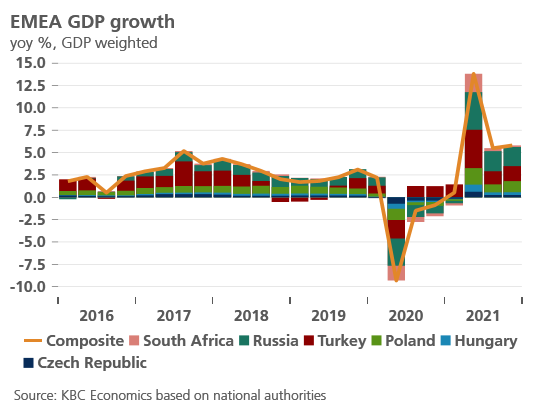

EMEA

CEE

The Russia-Ukraine war will affect CEE economies through several channels: first, a direct trade channel, implying a loss of export markets; second, an inflation channel via higher commodity prices; and third, a confidence channel prompting increased risk aversion. Regarding the trade channel, CEE export exposure to the Russian economy is relatively limited. Inflation, instead, is the main channel through which the conflict in Ukraine will, in our view, affect the CEE economies. A broad range of commodities have rallied due to the Russian aggression, most notably natural gas and crude oil. The CEE region appears particularly vulnerable to disruptions in natural gas flows from Russia with all regional economies being highly dependent on Russian imports: based on the Eurostat data, the share of Russian gas imports is largest in the Czech Republic (100%), followed by Hungary (95%), Slovakia (85%) and Bulgaria (75%). The CEE reliance on Russian oil imports is lower but still notable and generally above the EU average.

Importantly, we see a considerable risk arising not only from elevated commodity prices, but also from a possibility of supply disruptions that would lead to rationing of gas/oil consumption, implying a significant hit to activity. Furthermore, as higher commodity prices will lead to more elevated and more persistent inflation in the CEE region, we expect some hit to consumer demand due to eroding purchasing power. In other words, a commodity-driven negative supply shock (implying higher inflation and lower growth) is set to be accompanied by a negative demand shock (implying lower inflation and lower growth). We think that the latter might be relatively sizable given that many households across CEE region have been already hit hard by elevated inflation in the last couple of months.

Central banks in the region are facing a particularly difficult dilemma of tackling inflation at a time of downside risks to growth. On the one hand, as inflation is moving rapidly away from the inflation target, central banks have become more concerned about a possible de-anchoring of inflation expectations. On the other hand, overly aggressive monetary tightening puts a still fragile post-pandemic recovery at risk, even more so now amid the negative spillover effects from war in Ukraine (for detail on CNB and NBP policy, see the most recent text on the CEE region in the KBC Economic Perspectives)

Turkey

Although Turkey’s economy surged by 11% in 2021, an ultra-loose monetary policy together with several unorthodox policy measures exacerbated underlying macroeconomic vulnerabilities. As a result, severe price pressures have taken hold with headline inflation surging to 61.1% yoy in March, up from 54.4% yoy in February. While unorthodox economic policies (as reflected, for example, in a strong FX pass-through from a significantly weaker lira) have remained a key driving force behind a broad-based escalation in inflation, a surge in global energy prices (energy CPI reached 103% yoy in March) is putting further upward pressures on prices. With another spike in headline inflation, ex-post real interest rates dropped below -47% in March, levels never seen in Turkey.

As policymakers continue to disregard the need for a sharp monetary policy tightening, headline inflation is expected to accelerate further, pushing real interest rates even more into negative territory. Against this backdrop, the Turkish lira is set to remain on a depreciation path. In addition, the weakening pressures are set to be reinforced by the negative spillovers from the war in Ukraine. In fact, Turkey stands out as one the most exposed economies to the Russia-Ukraine war, as higher commodity prices and lower tourist receipts are likely to result in an even sharper widening of the current account deficit.

Overall, we maintain the view that until more orthodox economic policies are introduced in Turkey, underlying macroeconomic vulnerabilities are unlikely to be tackled. Unorthodox measures such as the new FX-linked TRY deposit scheme provide only short-term and very fragile stability. In other words, without solid macroeconomic anchors, inflation will remain well above desirable levels and the lira will depreciate further, while remaining vulnerable to shifts in local and global risk appetite.

Russia

Russia’s economic outlook has been rapidly overtaken by the fallout from the war in Ukraine. Given the unprecedented scale of economic sanctions, Russia’s economy is poised for a deep recession in 2022. Although uncertainty surrounding forecasts is extremely elevated, the economic decline (largely due to a sizable contraction in domestic demand) will likely exceed the depth of real GDP contraction recorded in the 1998 (-5.3% yoy) and 2009 (-7.8% yoy) episodes. In addition, a sharp contraction in economic activity in 2022 is unlikely to be followed by a swift bounce-back given the likely longer-lasting effects of sanctions.

Interestingly, the ruble has now recovered all its losses caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. However, the ruble strength is somewhat artificial, since it is supported by strict capital controls (limiting the deficit on the financial account) implemented in the aftermath of Russia-Ukraine war-related sanctions. At the same time, Russia is experiencing large current account inflows, driven by its oil and natural gas revenues. However, this effect could be partly reversed, should the EU impose tough(er) restrictions on Russian oil and gas exports. Finally, the ruble foreign exchange market remains very shallow with only limited liquidity, implying that very small volumes can cause large appreciation in the exchange rate.

South Africa

South Africa, like Brazil, is another commodity exporter (particularly of gold, platinum, and iron ore) whose assets have generally outperformed in recent weeks (the ZAR has appreciated 9.7% versus the USD so far this year). High frequency indicators have also held up well, with the Markit Composite PMI improving to 51.4 in March. At the same time, however, consumer confidence declined further in the first quarter, which may reflect rising inflation. However, while headline inflation has increased in recent months (reaching 5.7% year-over-year in February), core inflation remains rather well-behaved at only 3.5% year-over-year, which is below the central bank's 4.5% target. The central bank started hiking its policy rate in November 2021 but has not needed to be as aggressive as some other emerging market central banks, implementing only 50 basis points of hikes so far to bring the policy rate to 4.0%. The hiking cycle is expected to continue through the end of 2022, bringing the policy rate to 5.75%, however, and GDP growth is expected to slow to 2.1% in 2022 from 4.9% last year.

Tables and Figures

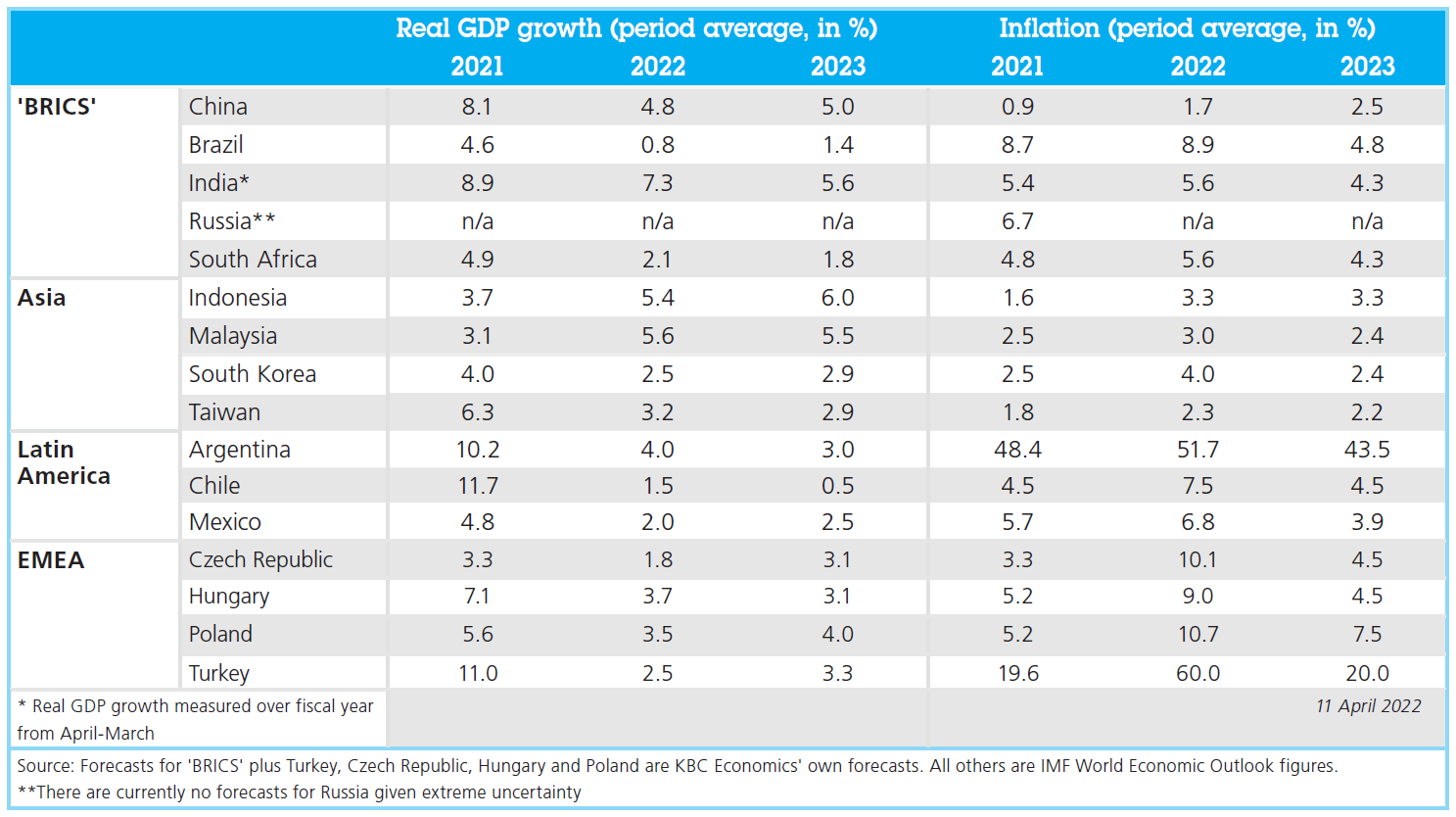

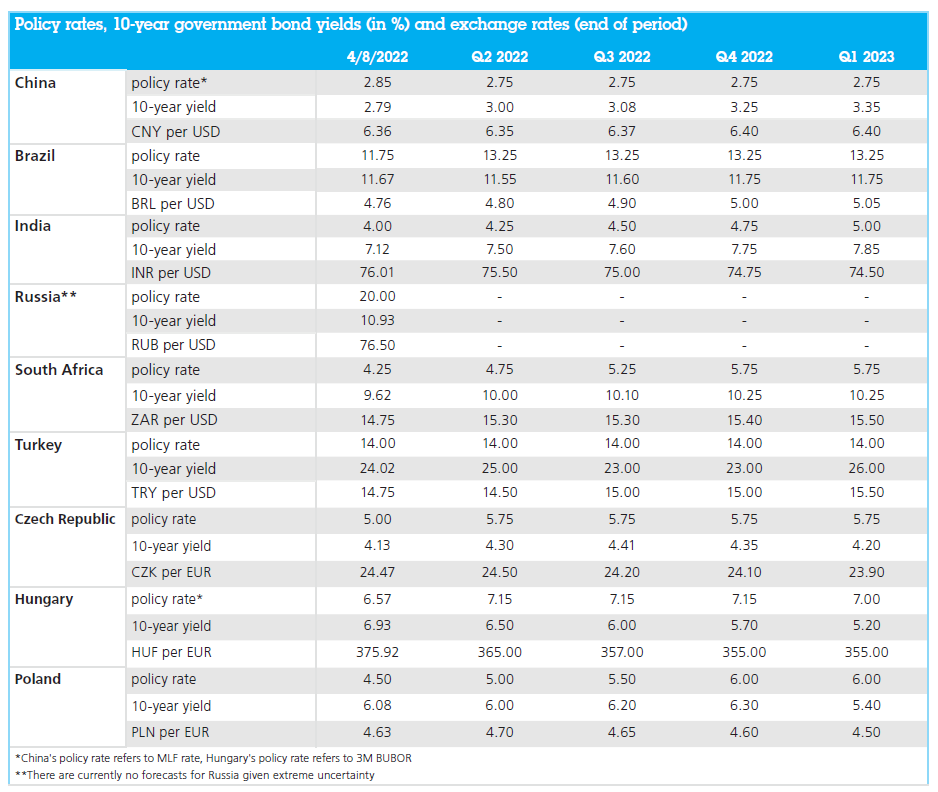

Outlook emerging market economies