Emerging Markets Quarterly Digest: Q2 2021

Content table:

Read the publication below or click here to open the PDF.

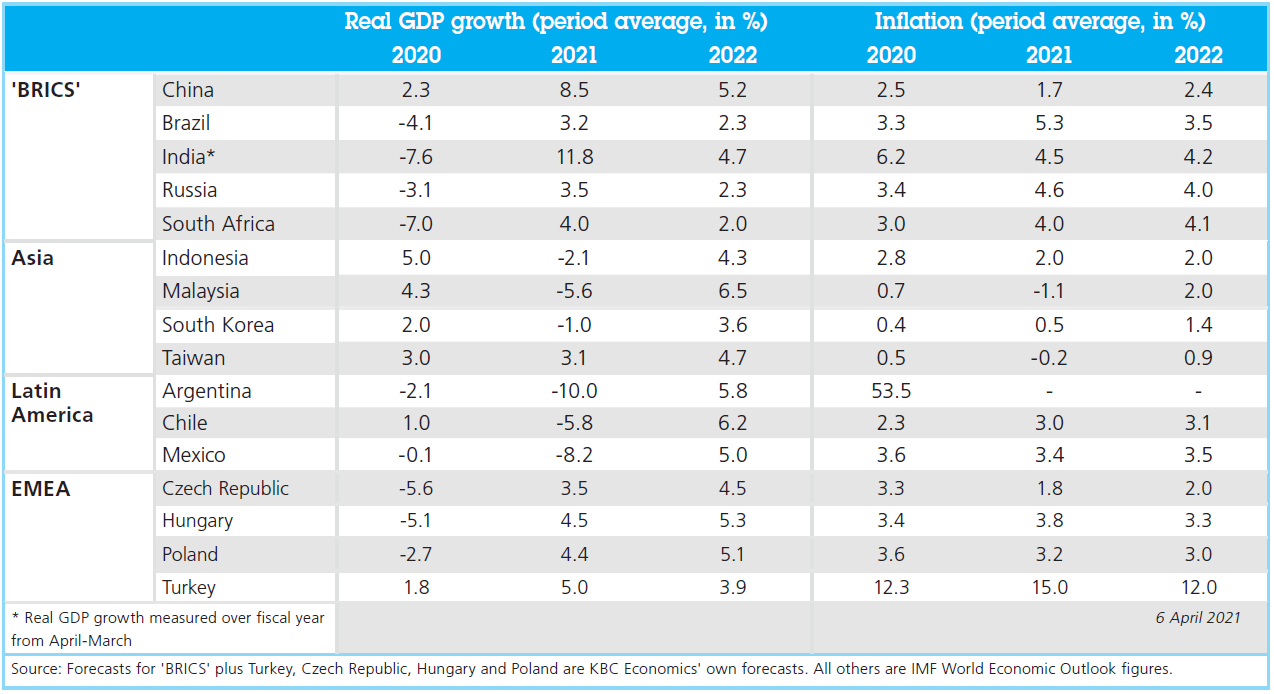

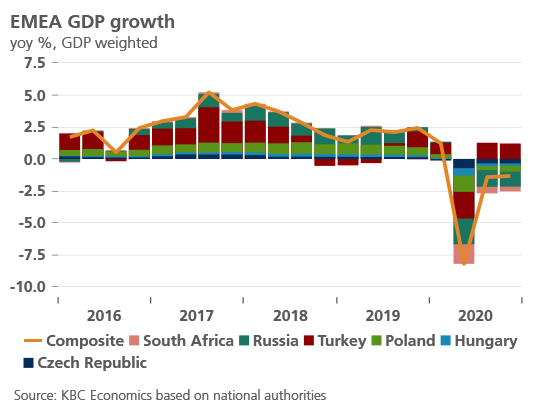

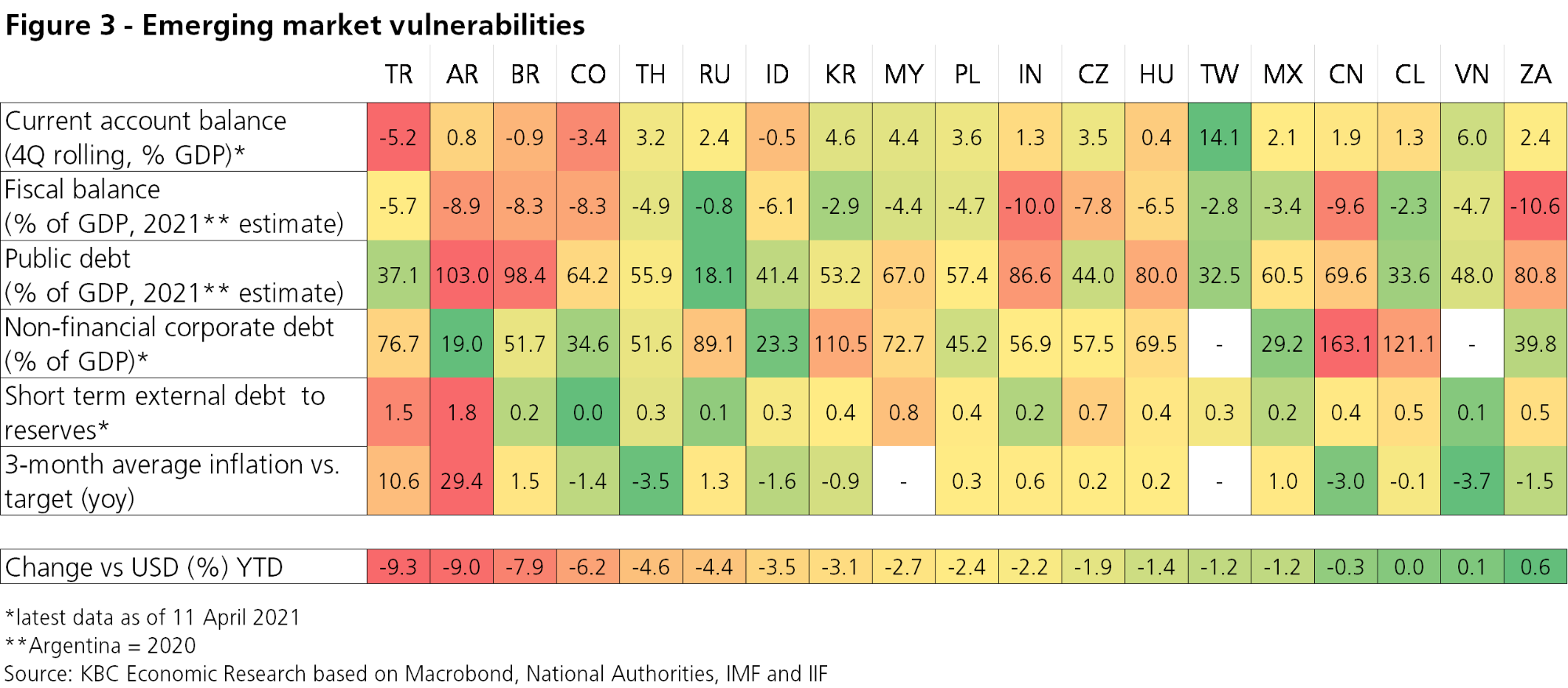

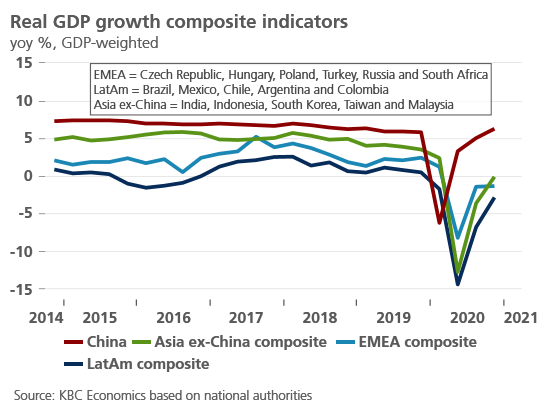

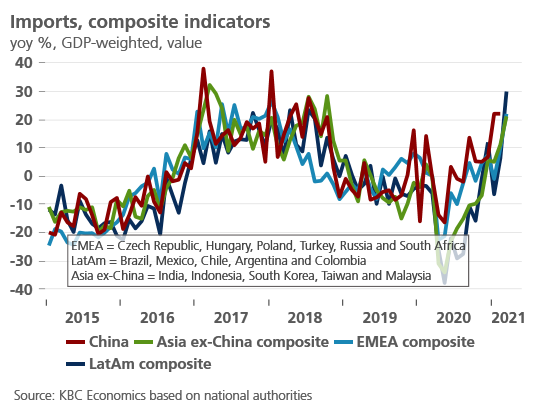

A fragile recovery ahead

The global economic recovery is becoming less synchronized due primarily to differing levels of fiscal stimulus and differing vaccination paces from one economy to the next. With the US set to record growth of over 6% in 2021, 10-year US interest rates have risen notably in recent months, setting the stage for a more complicated recovery phase in emerging markets. While higher global yields may lead to more volatility in capital flows to emerging markets, emerging markets generally have larger macroeconomic and external buffers compared to 2013, when market fears of Fed tapering led to significant capital outflows. However, some emerging markets are still vulnerable to a tightening of financial conditions, especially those with deeper fiscal deficits and higher debt levels, particularly external debt. An additional headwind for some, but certainly not all, emerging markets is rising inflation pressure (particularly headline inflation). Hence, the message from the last iteration of this publication remains mostly unchanged: 2021 is still set to be a much better year for emerging market economies compared to 2020, but some will face a steeper climb and higher risks than others.

Vaccination progress varies

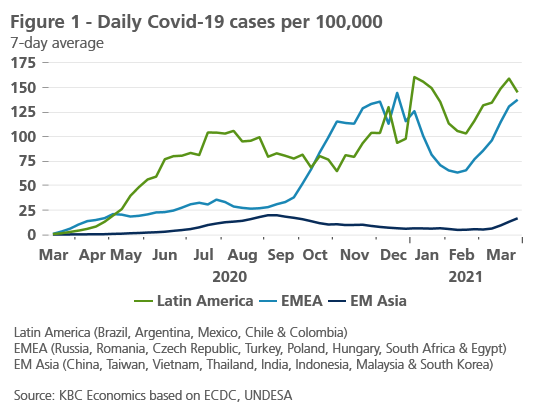

Pandemic developments remain the key driver of the economic outlook for both emerging markets and advanced economies alike. From a regional perspective, both Latin America and countries in Central and Eastern Europe are seeing a rising trend in daily new cases, while case rates in Asia generally remain much lower (figure 1). For most Latin America countries, the surge in new cases has been attributed to the spread of a new, more transmissible variant (the so called P1 variant), and developments are particularly dire in Brazil, where daily deaths have reached 4,000.

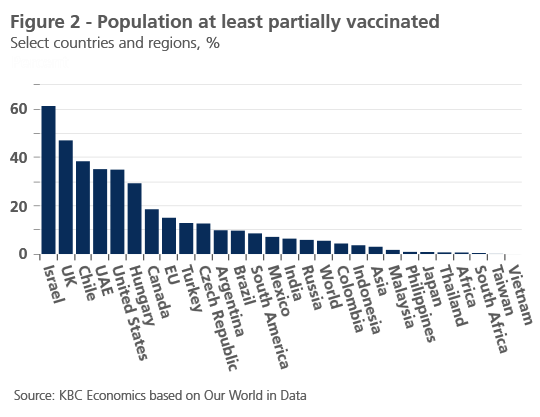

The rollout of vaccination campaigns does provide hope that the pandemic will eventually be brought under control, but vaccinations are, as expected, progressing at varying rates from one country to the next. In general, lower- and middle-income economies are well behind higher income economies in terms of the percentage of their populations that have received at least one dose (figure 2). And among emerging markets there is also a clear distinction between the vaccination pace for middle-income economies and lower-income economies.

There are, meanwhile, some wealthier emerging markets that are on top of the global leader board in terms of vaccination pace, such as Chile, which has already administered at least one shot to 37% of its population. However, despite Chile’s progress, new case rates continue to rise, which may hint at reports that the Sinovac vaccine (on which Chile is relying heavily) is only effective after the second dose. With many low- and middle-income countries counting on the Sinovac vaccine and the AstraZeneca vaccine, the latter of which has run into a series of setbacks in recent weeks, the inoculation process for emerging markets may be faced with further challenges ahead.

Leading to desynchronization

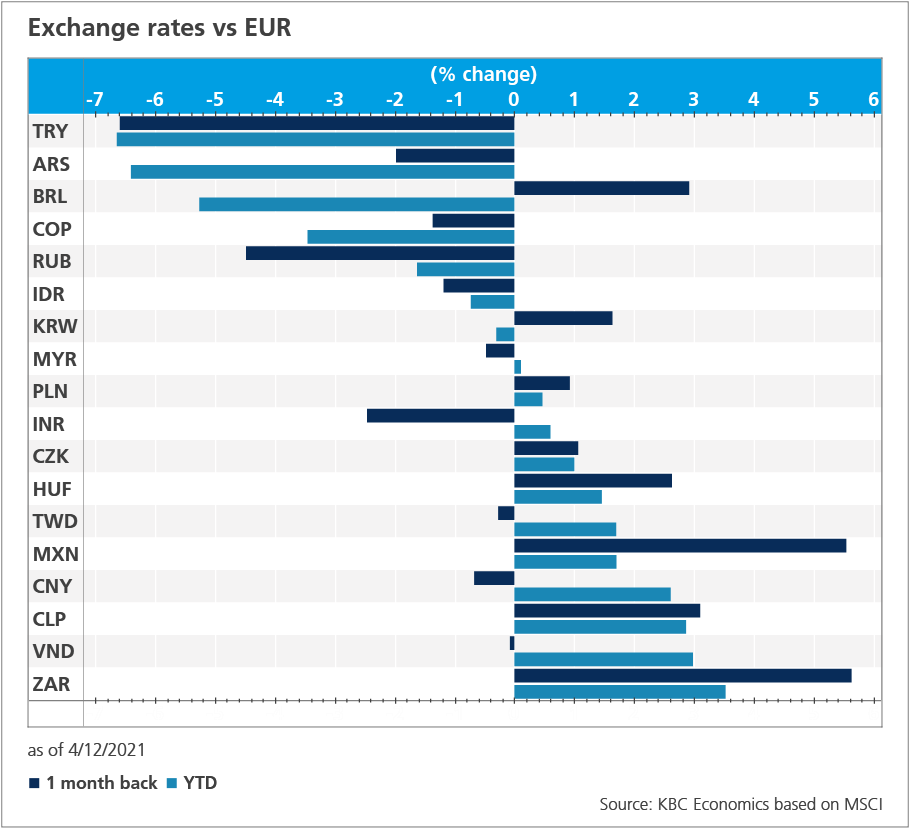

This slower vaccination pace for emerging markets compared to wealthier economies, and in particular compared to the US, will only further the desynchronization of the global economic recovery, as in most cases, sufficient inoculation of the population is a key prerequisite for a full normalization of the economy. With many pandemic-related restrictions in the US already being lifted, and with the economy supported by the two fiscal packages passed in December 2020 and March 2021 (with a new infrastructure package potentially on the way), US GDP growth is expected to recover to 6.2% in 2021, and the labour market continues to steadily improve. As a result, the yield on the 10-year government bond in the US rose from 0.93% at the beginning of the year to around 1.7% as of the first week of April. While an improving growth outlook in the US is usually good news for the global business cycle, many emerging markets are lagging behind in the economic recovery, and rising US interest rates may mean a possibly premature tightening of financial conditions and potentially more volatility in capital flows and exchange rates.

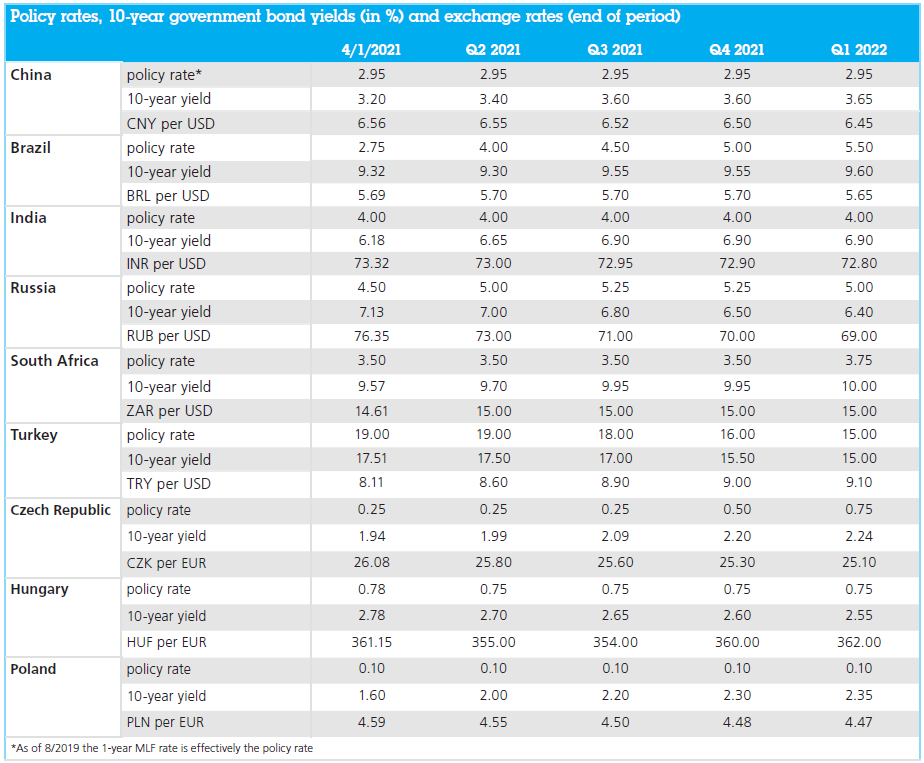

Hiking early and fast, but not everywhere

Already we have seen three emerging market central banks—Brazil, Russia and Turkey—increase policy rates in March, raising questions of whether the emerging market hiking cycle is starting earlier than expected, and whether tighter financial conditions could disrupt the economic recovery. While all three economies are in very different positions from a macroeconomic perspective and their respective central banks hiked for different reasons (see below for more details), it is worth noting that the currencies of Brazil, Turkey and Russia have been among the weakest emerging market currencies relative to the US dollar since the start of the pandemic. Also notable is the fact that all three countries have seen a substantial increase in headline inflation since the beginning of the year above their respective inflation targets. While Brazil and Russia are expected to introduce further rate hikes in the coming months, not all emerging markets are expected to charge forward with a hiking cycle, especially not those with still subdued inflation dynamics and/or better external buffers (figure 3). An important element of this outlook is the Fed’s current insistence that policy rates will be kept at current levels at least through 2024, despite markets pricing in earlier tightening of policy. A change in Fed communication on this note could cause heightened turmoil in emerging markets.

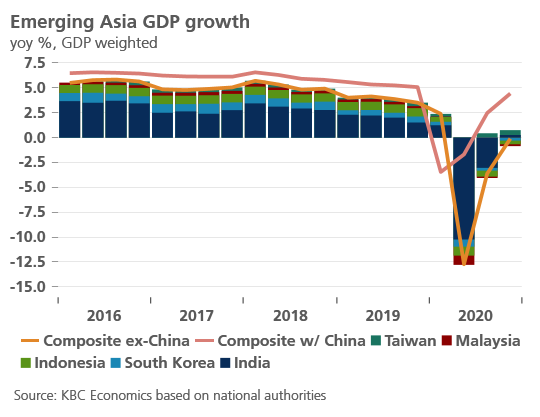

Emerging Asia

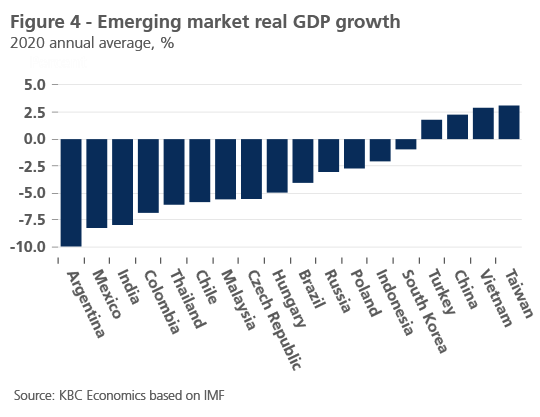

Emerging Asia remains well situated to benefit from the global recovery this year, with most economies in the region less vulnerable to rising US interest rates. In general, macroeconomic buffers, such as current account balances, fiscal balances and reserve coverage are strong. The better fiscal situation for these economies means less pressure to quickly consolidate budgets and withdraw fiscal support too early. Higher current account surpluses, manageable external debt balances and well contained inflation also mean more breathing room to maintain accommodative monetary policy, even as global yields rise. Furthermore, some economies in the region showed high resilience to the economic effects of the pandemic throughout 2020, with Taiwan, Vietnam and China all registering positive GDP growth for the year (figure 4).

One clear risk factor for Asia, however, is the relatively slower rollout of vaccination campaigns compared to elsewhere. However, given that the region as a whole was generally able to keep the spread of the virus better under control throughout 2020, the slower pace of inoculations is not currently a major headwind to the economic recovery.

China

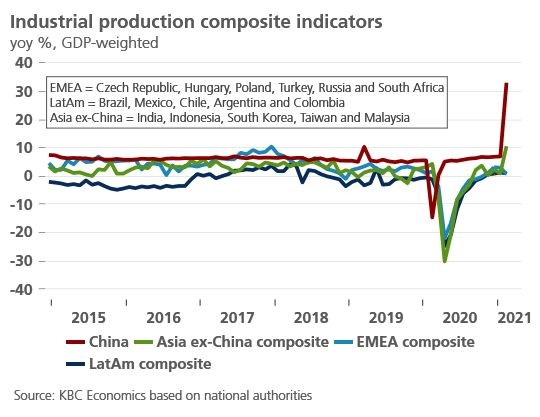

The economic outlook for China remains unchanged with real GDP expected to reach 8.5% in 2021 before moderating to 5.2% in 2022. Available activity data for Q1 suggests that the economy remains on strong footing, with industrial production growth accelerating on a quarterly basis in both January and February (0.66% and 0.69% respectively). The NBS manufacturing and service sector business surveys also both improved in March.

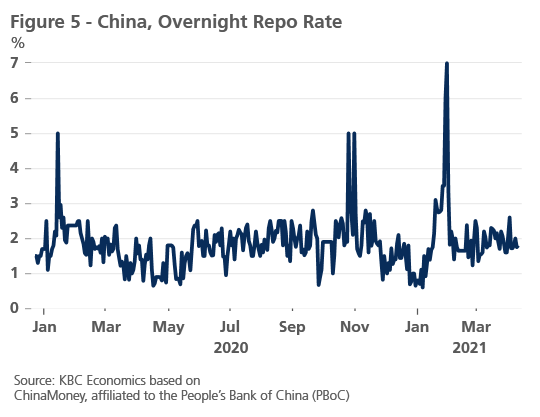

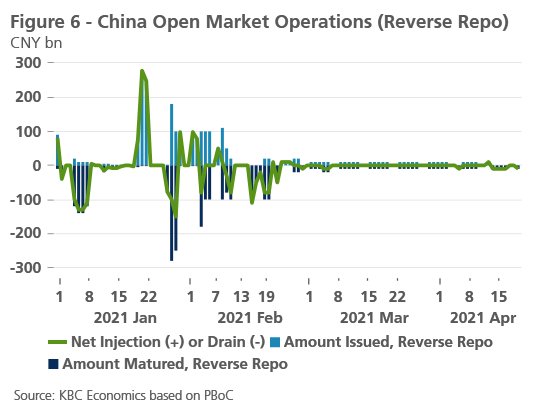

The main question surrounding China’s outlook, however, is the approach the government will take toward potentially tightening policy. Concerns flared up at the beginning of February when the overnight repo rate jumped after some liquidity was withdrawn via open market operations ahead of the Spring Festival period. However, PBoC officials quickly spoke out against the idea that there would be a sudden sharp change in policy this year. The repo rate has since resettled around levels seen at the end of 2020, and net injections or withdrawals of liquidity via open market operations have been remarkably stable around zero since the end of March (figure 5 and 6).

However, questions regarding the magnitude of policy stimulus (or its withdrawal) in China this year are far from settled. Though the government’s latest 5-year plan, which was approved in March, did not include the usual medium-term growth targets inherent in the past plans, the government did set a growth target above 6% for 2021. Because most analysts see growth in 2021 easily surpassing that rate thanks to a low base in 2020 and ongoing recovery, the announcement was seen by some as a signal that more policy tightening could be on the way. Given the government’s insistence that the removal of the growth targets was a way to provide more flexibility, it is probably best not to read too much into the figure. Rather, the easily reachable figure will give the government room to target a lower rate of growth in 2022, as growth dynamics normalise, and the Chinese economy returns to its medium-term trend of moderately declining growth.

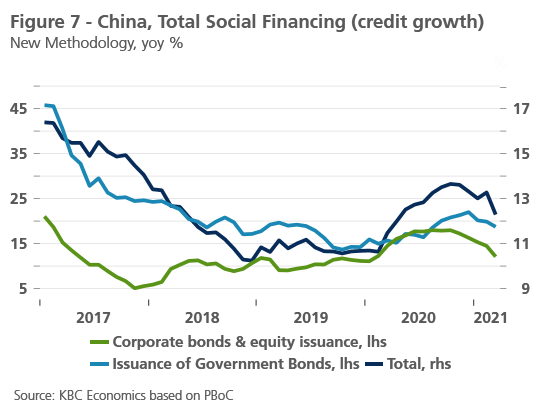

Still, some deceleration of credit growth can be expected as the government aims to reign in both corporate sector debt and risks of a bubble in the real estate market. Indeed, the PBoC has reportedly instructed banks to curtail credit supply this year. However, it must be remembered that corporate sector deleveraging has been a long-term goal of the Chinese government, disrupted by the economic impact of the US-China trade war and then by the Covid-19 crisis. Hence, some deceleration of credit is in line with a steady normalisation of growth dynamics. Our outlook therefore remains that policy will be moderately tightened this year, with policy rates stable, state-owned enterprises stepping back somewhat from the important role they played in stabilising growth through the pandemic, and credit growth decelerating from temporarily elevated levels (figure 7).

India

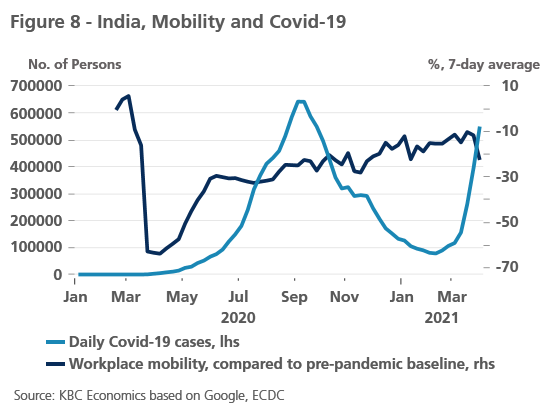

India’s economic outlook is increasingly complicated by its current resurgence of the pandemic since the beginning of March, with daily Covid-19 cases quickly reaching the previous wave’s peak. Mobility in India has since dropped off, though it still remains above the levels seen during the first wave in the spring and summer (figure 8). Business sentiment surveys have so far held up in March, but it is likely there will be some deterioration evident in next month's figures. While our outlook for the fiscal year 2020 growth figure has only been slightly downgraded to -7.6% (from -7.4% last month), we downgraded our outlook for FY 2021 from +12.4% to 11.8%. While this figure is still quite high on its surface, much of it reflects the low comparison level in FY 2020. However, the economic recovery is still expected to accelerate later in 2021. Though the vaccine rollout is proceeding slowly, with only 6% of the population partially inoculated, the pace of vaccination is picking up. Risks to the downside still remain, however, with reports of vaccine shortages in certain regions threatening to slow the rollout further.

Despite a recent uptick in headline inflation (5.0% yoy in February) the central bank (RBI) is expected to remain on hold through 2021, particularly given the new headwinds to growth. And despite the recent uptick, inflation pressures have come down significantly relative to where they were in 2020 thanks to declining food prices. However, core inflation remains somewhat more concerning at 5.9% yoy in February, suggesting the RBI will likely be keeping an eye on its further development.

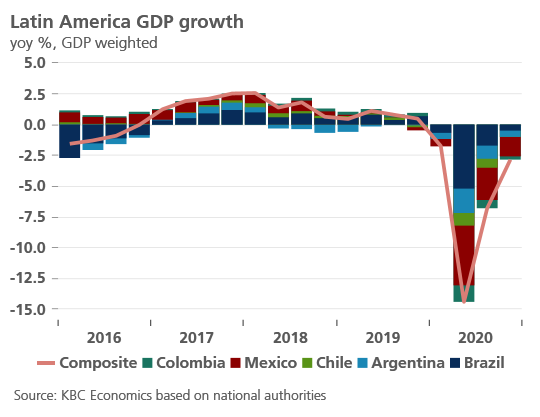

Latin America

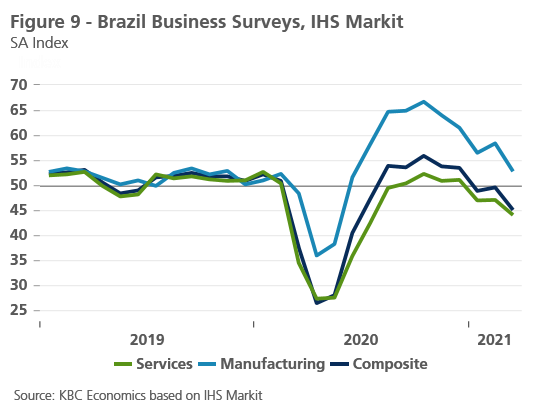

The economic outlook in Latin America remains particularly precarious given the current surge in Covid-19 cases highlighted above. Making matters worse is the fact that many economies in the region had experienced some of the sharpest declines in GDP in 2020 (Peru: -11%, Argentina: -9.9%, Mexico: -8.2%, Ecuador -7.5%, Colombia: -6.9% and Chile: -5.8%). While the largest economy in the region, Brazil, fared somewhat better, with a contraction of -4.0% in 2020, the situation has swiftly deteriorated. Brazilian business sentiment surveys have tumbled since the fourth quarter of 2020, in line with the negative pandemic developments that have overwhelmed the healthcare system (figure 9).

The country has been further plagued in recent weeks by significant downward pressure on the currency as pandemic developments threatened not only the economic recovery but also the country’s already weak fiscal picture. Brazil’s government debt-to-GDP ratio reached nearly 99% of GDP in 2020 according to the IMF, and the pandemic has only exacerbated the situation, with the deficit rising from 5.8% of GDP in 2019 to 13.4% of GDP in 2020. Given the need to provide fiscal further support as the virus continues to spread, the deficit is expected to remain wide in 2021.

On top of the pressure on the currency, inflation has been rising steadily since May 2020, driven first by higher food prices and more recently by the increase in energy prices. At 6.1% yoy in March, headline inflation has now surpassed the central bank’s upper limit of 5.25%. Though core inflation remains more muted (2.9% yoy in March), there has been some upward momentum in core inflation as well. The inflation picture, together with the substantial depreciation of the Brazilian real year-to-date appear to be the main factors behind the central bank’s decision to hike rates at its March meeting by a higher-than-expected 75 basis points to 2.75%. This initial rate hike was likely the beginning of a front-loaded hiking cycle with another 75 basis point increase possible at its next meeting in May. The real has since stabilised versus the US dollar, but more volatility is likely given Brazil’s high vulnerabilities.

EMEA

Central and Eastern Europe

Since February, there have been strong increases in the number of daily Covid-18 cases in the CEE region, particularly in Poland, Hungary, and Bulgaria. The Czech Republic and Slovakia, where the latest wave of the pandemic appeared earlier, are currently seeing an improvement in the situation, but the number of newly reported cases remains at very high (and volatile) levels. However, the economic outlook for the region remains optimistic in the medium term, particularly given ongoing vaccination efforts, which are roughly on par with the EU average, except for Hungary, where they are substantially higher, and Bulgaria, where they are somewhat lower.

The latest pandemic waves have, however, complicated and delayed the region’s economic recovery. While the chip shortage hampered the export-oriented automotive industry in Central Europe at the beginning of the year, in March the negative effects of the pandemic made themselves felt once again as restrictive measures were either extended or reintroduced. As a result, we have revised down our growth estimates for the first quarter of the year to flat or slightly negative, which is in line with the downward revision of the Q1 growth estimate for the euro area (to 0% quarter-on-quarter).

This more cautious growth estimate for Q1, however, is to some extent compensated by an expectation that there may be a positive compensating effect from Q2 on. As a result, we kept our annual growth forecast for 2021 on balance unchanged for the Czech Republic (3.5%), Hungary (4.5%) and Bulgaria (3%). Only our annual growth outlook for Slovakia was downgraded to 3.7%, based on our estimate of a severe contraction in Q1, which is unlikely to be offset in the remaining quarters of 2021 (for more details, please see our latest economic update for the region: Perspectives Central and Eastern Europe)

Russia

The Central Bank of Russia (CBR) started its tightening cycle in March, defying market expectations of an unchanged policy stance. Against the background of higher-than-expected inflationary pressures and stronger demand conditions, the CBR hiked its key rate by 25 bps to 4.5%. Furthermore, the central bank provided hawkish forward guidance, signalling a need to return to the neutral monetary policy rate estimated in the range of 5.00-6.00%. As a result, we have upgraded the expected policy path towards a faster normalisation of interest rates, and now see the CBR delivering an additional 75 bps hike in total by the end of Q3 2021. Still, we await the CBR’s April meeting which should shed more light on the central bank’s medium-term plans (as its model-driven policy rate path will be published).

The tighter expected monetary policy stance should help anchor inflation expectations amid pro-inflationary risks. Although headline inflation spiked to 5.7% yoy in February (vs. the inflation target of 4.0%), this is largely a result of temporary factors such as higher food prices or supply-side disruptions. The CBR, however, appears concerned about secondary effects via inflation expectations, as well as deteriorating geopolitics. The latter reflects the risk associated with the new US sanctions and increased ruble volatility (as a source of inflationary pressures). Therefore, the CBR’s recent monetary response should be also seen as a step to raise the buffers against downward pressures on the ruble.

Turkey

Following a pronounced shift to a more orthodox monetary policy in late 2020, Turkey saw another U-turn in March. Two days after the hawkish decision to hike the policy rate by 200 bps to 19.00%, President Recep Erdogan unexpectedly replaced the central bank’s governor Naci Agbal with Sahap Kavcioglu who is known for holding more dovish views. This was already the third replacement of the central bank’s governor over the past two years. Although we considered governor Agbal’s ‘tighter for longer’ policy stance unsustainable in the long run due to the unchanged institutional set up (see also Economic Opinion - Turkey: new beginning?), the timing of the replacement is surprising, reversing the credibility-building effort of the past months.

The major victim of the shocking change in the central bank’s leadership has been the Turkish lira. While during Agbal’s term the lira gained almost 20% against the US dollar, it has fallen by 11% since the removal of the market-friendly governor. What’s more, lira weakness reveals underlying macro vulnerabilities of the Turkish economy, including the weak external position, large external financing needs and low foreign reserves. Persistently high inflation, in particular, remains a source of concern (accelerating to 16.2% yoy in March), limiting the space to manoeuvre for the central bank. All in all, there remains substantial uncertainty around how monetary policy will change under the new governor with little forward guidance so far. While we now pencil in a less hawkish policy stance with the start of the easing cycle in the third quarter, there is a notable risk of a much more front-loaded cutting cycle.

South Africa

Though South Africa is another emerging market that stands out for its vulnerable macroeconomic positions – particularly a high government debt ratio (77% of GDP) and wide fiscal deficit (12% of GDP) – the South African rand has been one of the best performing emerging market currencies against the US dollar this year. In part, this reflects stronger commodity prices and new agreements with Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson to secure additional vaccine doses. It also reflects some brighter activity data with the Markit composite business sentiment survey remaining in expansionary territory (above 50) since October 2020. In addition, both core and headline inflation in South Africa remain subdue (2.6% and 2.9% yoy in February respectively) and well below the central bank’s 4.5% target, giving the central bank space to keep rates steady despite rising US yields. On the Covid-19 front as well, South Africa has managed to bring its second wave under control, despite the spread of a more transmissible variant. Though mobility indicators still remain weak, they have improved relative to the lows reached in December 2020 and January 2021. As such, though the outlook remains somewhat fragile for South Africa, there are optimistic signs on the horizon.

Tables and Figures

Outlook emerging market economies