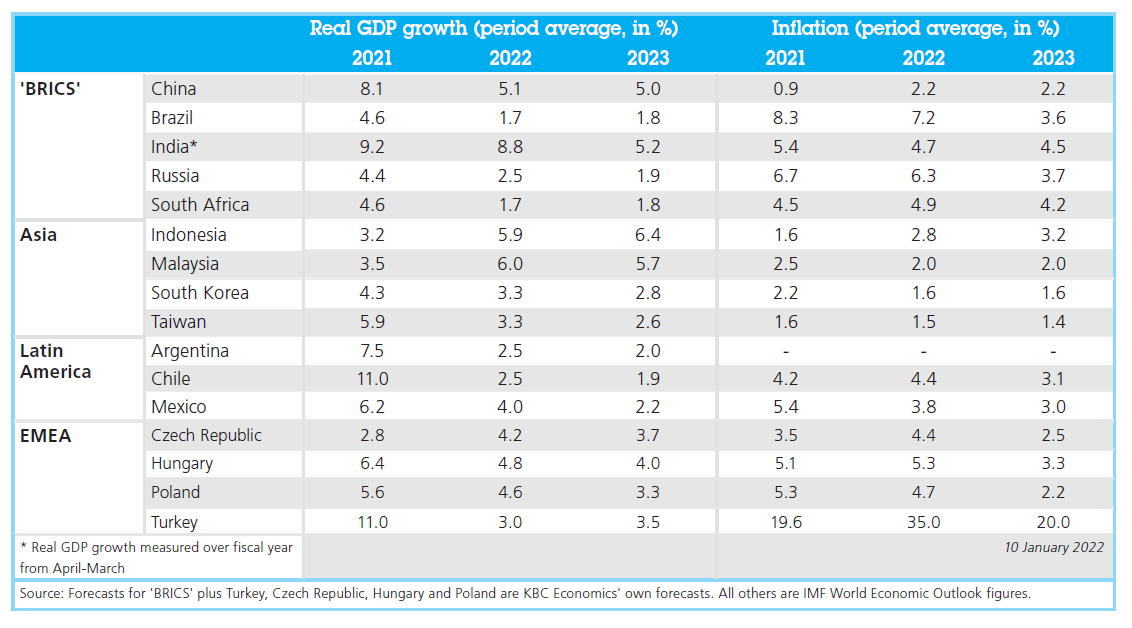

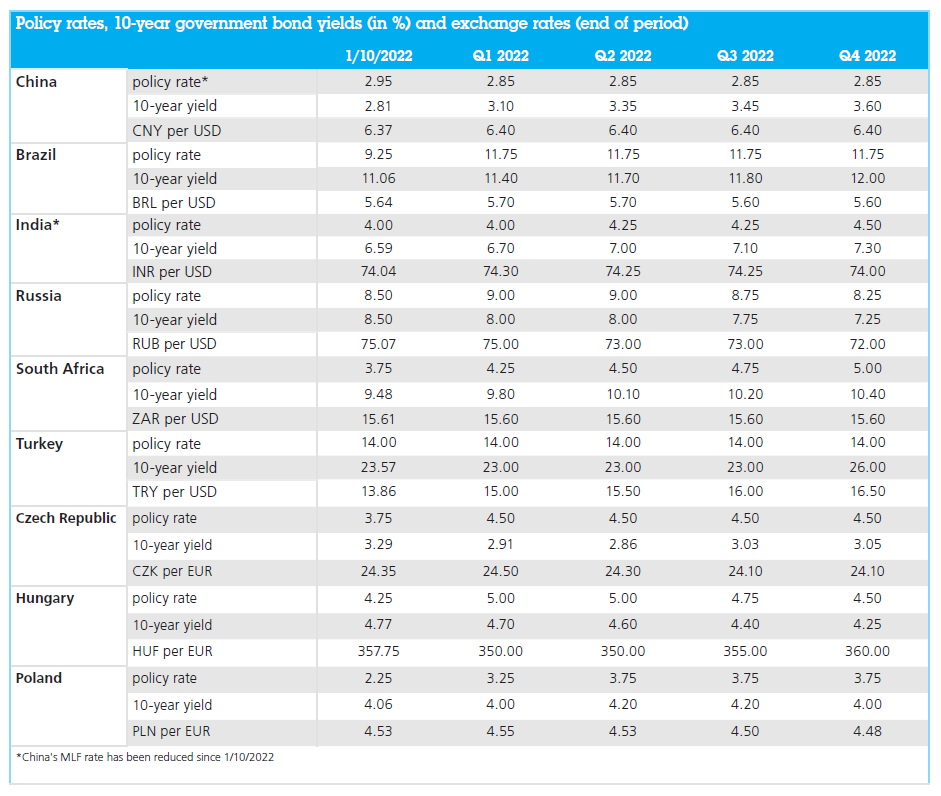

Emerging Markets Quarterly Digest: Q1 2022

Content table:

Read the publication below or click here to open the PDF.

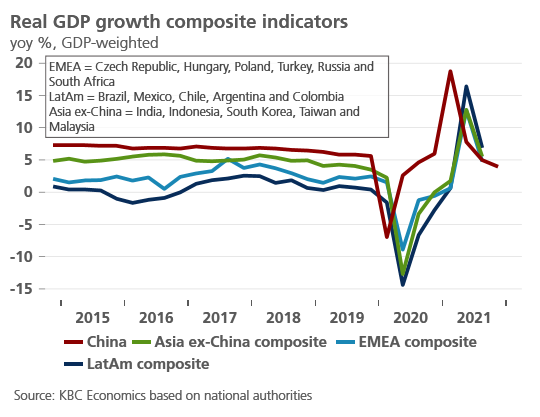

2022 rising

At its outset, the 2022 global economic context can be defined by three major developments: rising Omicron cases, rising inflation pressures, and rising interest rates. All three of these factors bring some uncertainty to an already challenging outlook for emerging markets, but the situation isn’t completely dire. The economic recovery continues – albeit at a slower pace and marked by both supply-side and covid-related disruptions. At the same time, vaccination rates are progressing in emerging markets, and there are early signs (e.g., South Africa) that the imminent Omicron waves may be short lived, with limited disruptions to economic activity. Finally, the fact that most central banks in emerging market economies appear willing to tighten policy rather than risk higher inflation expectations becoming entrenched will support financial market stability in the face of a tightening Fed.

In addition to these three major economic developments, however, rising geopolitical tensions between Russia and the West also bring further economic uncertainty to the global economic landscape. Any escalation that results in a spiral of new sanctions could impact not only growth developments in Europe, but also global energy prices.

Covid Surge

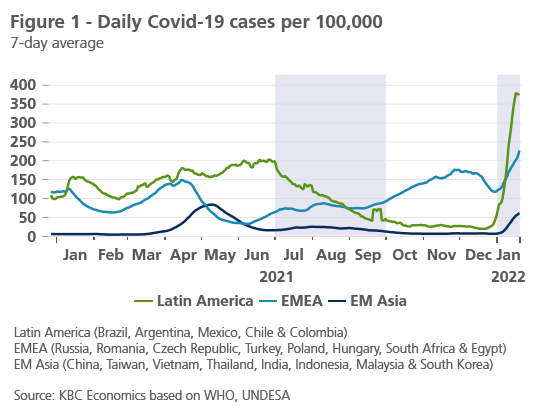

Covid-related developments remain a key driver of the economic outlook in early 2022, especially as the more transmissible Omicron variant spreads rapidly throughout the world. The respite certain regions (particularly Asia and Latin America) saw during the fourth quarter as Delta waves eased has now given way to renewed surges in cases which are expected to far surpass previous peaks (figure 1).

However, throughout the second half of 2021, emerging markets did make substantial progress in vaccinating their populations, with many countries going from 10% or less of the population vaccinated, to more than 60% vaccinated, with those figures still rising. This, together with the reported lower severity of Omicron induced cases provides hope that policymakers will be able to avoid reinstating strict lockdowns, weakening further the link between rising caseloads and economic activity. However, it is still likely that surging cases, will lead to some further supply-side disruptions due to absenteeism (whether from illness or quarantine requirements). This remains particularly important in China, where the government continues to follow a strict ‘zero-covid’ policy to keep cases low.

While this ‘severe but short-lived’ outlook is also the baseline view for how we expect Omicron to impact advanced economies, there are some factors that increase the risks for emerging markets. First, many emerging markets relied partially or nearly fully on the Chinese-made non-mRNA vaccines, which reportedly offer less protection against Omicron. Second, the healthcare systems in some less wealthy emerging markets may come under pressure more quickly. There is a clear discrepancy, for example, in the number of hospital beds per 1,000 people in lower-middle-income countries (0.77) versus upper-middle-income or high-income countries (3.9 and 5.25, respectively), according to the World Bank.

Inflation, interest rates, and EM vulnerabilities

Omicron is not the only shock that altered the global economic landscape in the fourth quarter of 2021. Though we noted in the last edition of this publication that the US Fed had begun signaling that some policy normalisation was on the horizon, November and December led to a substantial further shift in communication from the Fed, and markets have subsequently priced in a much earlier and more significant tightening of policy in the US over 2022. Specifically, the Fed has accelerated the pace of its tapering, leaving room for the central bank to implement its first 25 basis point rate hike as early as March 2022, followed by three more rate hikes this year. The December Fed minutes also suggested that balance sheet normalisation (i.e., shrinking) could start “relatively soon after beginning to raise the federal funds rate.”

Fed tightening cycles and subsequent rising benchmark interest rates can have significant implications for emerging markets, particularly for those emerging markets with large external imbalances (such as high current account deficits or dollar-denominated debt). At the outset of the pandemic, major advanced central banks pumped substantial amounts of liquidity into the global financial system and the US 10-year benchmark yield fell from 1.92% at the start of 2020 to 0.54% by mid-March. This came on top of policy easing the Fed had started in 2019 in the face of slowing growth. This easing provided room for emerging markets to follow suit, with almost all slashing their policy interest rates and many embarking on quantitative easing for the first time – a policy tool previously seen as only available to advanced economies. Lower interest rates not only helped stabilise financial systems in the wake of the pandemic, but also allowed emerging markets to borrow more cheaply and help finance both the health expenditures related to the pandemic and the economic recovery efforts.

Now, interest rates are once again on the rise, triggering a repricing across markets which can have implications for capital flows to emerging markets. According to the IIF (Institute of International Finance) emerging markets ex-China experienced a ‘de facto’ sudden stop in December 2021 given lower expectations for growth in emerging markets faced with higher inflation. The repricing of the Fed outlook raises risks of weakening capital inflows, and possibly also outflows, in early 2022 as well.

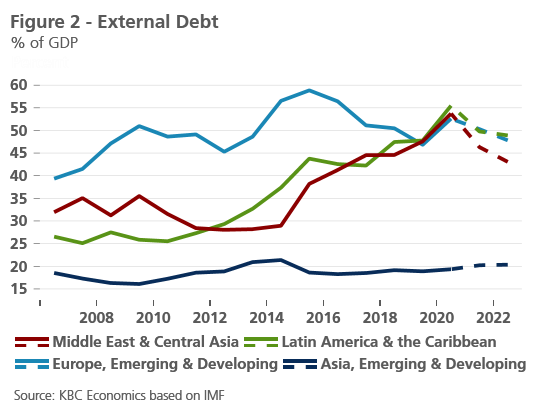

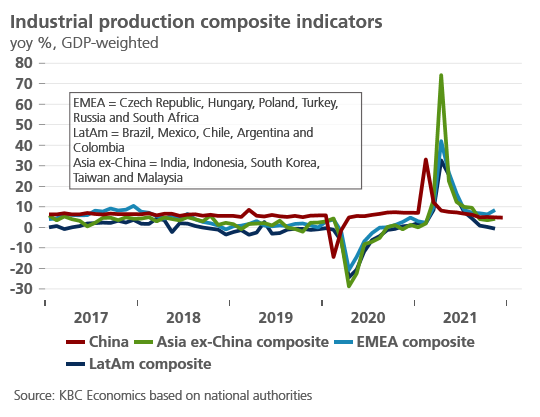

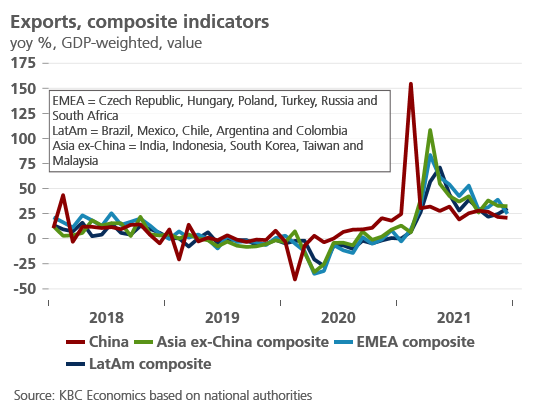

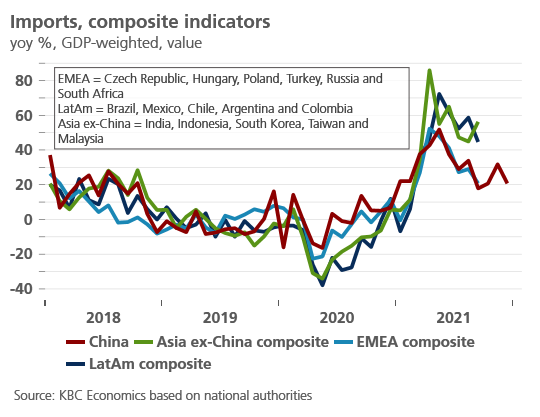

As is always the case, some emerging markets are better positioned than others. Emerging Asia in particular has far lower external debt relative to GDP than peers in Latin America or EMEA (figure 2). Current accounts are also generally in surplus in the region, with the few exceptions (Thailand, Vietnam) having only very limited current account deficits (both 1.6% of GDP on a 4Q-rolling basis as of Q3 2021). Strong external demand has supported this, with export volumes for Asian emerging markets and China still running well above the pre-covid trend. Current accounts have also improved in Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, South Africa and Russia since the start of the pandemic. While early in the pandemic this reflected a sharp drop in consumer demand, external demand and high commodity prices have since supported the trend. Overall, this suggests a less abrupt adjustment of the current account would be necessary in case of substantial capital outflows or volatility.

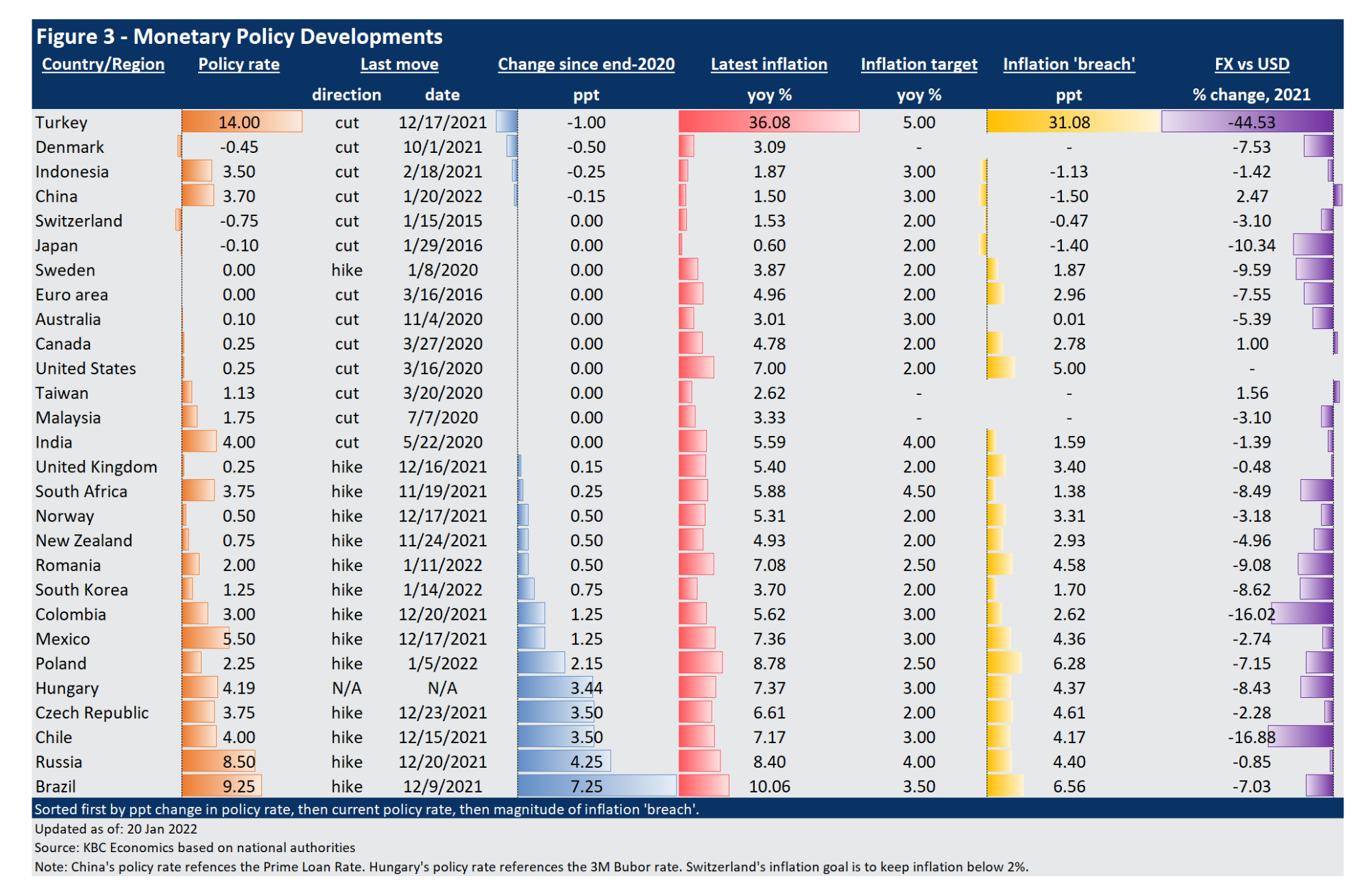

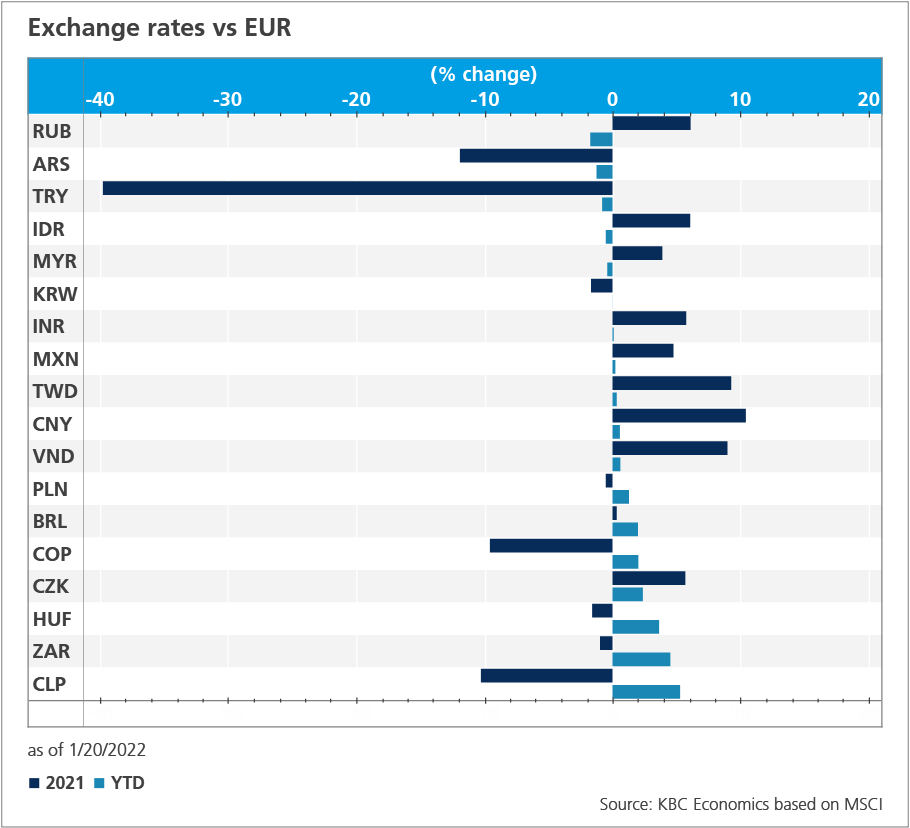

Still, emerging market assets may in be for a bumpy ride ahead after an already difficult 2021. Nearly all major emerging market currencies depreciated versus the US dollar last year, with the exceptions of the VND and the CNY. This currency weakness was despite central banks in most emerging markets starting significant hiking cycles (figure 3). Brazil’s central bank, for example, hiked its policy rate by 725 basis points in 2021 to a rate of 9.25%, as the BRL depreciated against the USD by 7%.

Of course, the general currency weakness among emerging markets signals the difficult economic path ahead. With inflation rates well above target in many countries, further central bank hiking will likely put a damper on the recovery. As is clear with the case of Turkey (see details below), however, the alternative would be worse for long-run growth and stability.

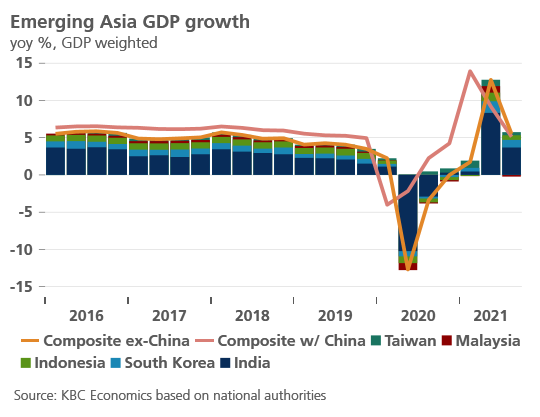

Emerging Asia

Though risks abound, most Asian economies start 2022 well equipped to face the main economic challenges posed by the current global context. On the whole, Asian economies ended 2021 registering a notable improvement in sentiment and activity indicators, with their current accounts generally in surplus, and with significant progress in getting their populations vaccinated (booster campaigns are slowly being rolled out as well). These factors, together with still elevated external demand despite some expected normalisation of consumption patterns in advanced economies, should support the growth outlook in the region in early 2022. Furthermore, inflation remains well behaved in much of the region, giving central banks some additional breathing room.

China

This year will once again be a balancing act for Chinese policymakers straddling the objectives of prioritising growth and addressing risks in the economy. While the government is expected to set an annual growth target around 5.5% (likely announced in March), even reaching that level will be difficult, with most estimates for 2022 currently set around or only slightly above 5.0%.

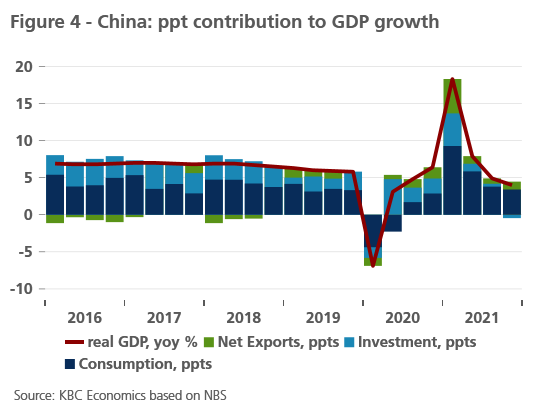

Looking back, real GDP grew 8.1% in 2021. While this figure is high in relative terms (for comparison, real GDP grew 6.0% in 2019 and 6.7% in 2018), it largely reflects the recovery from an abnormally low growth rate in 2020 due to the pandemic. Behind the 2021 headline figure, there was a notable slowdown in year-over-year terms, to levels that are generally below the pre-Covid trend – from 18.3% in Q1 (driven by 2020 covid base effects) to 4.0% in Q4 (figure 4). This slowdown reflects not only the long-standing downward trend in GDP growth as China grapples with an aging population and the challenge of shifting growth engines away from debt-fuelled investment toward consumption (and industrial upgrading), but also some near-term headwinds that weighed on growth in 2021. These headwinds included China’s regulatory crackdown on a number of sectors that intensified in July and August, an energy crunch in September that disrupted industrial output, and the fallout from the liquidity crisis among real estate developers that was triggered by the government’s efforts (including the “Three Red Lines” policy) to address over-leverage in the sector.

Supporting growth without relying on a strong expansion in construction activity will be one of China’s main economic challenges in 2022. Though Evergrande, which was placed in the category of “restrictive default” by Fitch in December and is currently going through a restructuring, is the most prominent of such cases, many other developers are also facing a liquidity crunch. Covid developments also present an important uncertainty for the economic outlook in China given the government’s strict ‘zero-covid’ policy, which has led to stringent lockdowns of various ports and cities at different times over 2021. Together with the global spread of the more transmissible Omicron variant, this policy approach, if maintained, risks leading to important economic disruptions in the beginning of 2022.

While risks to the outlook for China have mounted over the past several months, and the long-term trend of slowing growth is expected to continue, the outlook isn’t all negative. While the quarter-over-quarter GDP figures in China can be difficult to interpret given lack of transparency on the seasonal adjustments made to the series, official data suggests that momentum picked up from 0.7% qoq in Q3 to 1.6% qoq in Q4. Strong export data and a recovery in industrial production throughout the fourth quarter confirms this trend. Furthermore, after several months of deceleration, credit growth (measured by total social financing) finally began to edge up, from 9.9% yoy in September to 10.3% in December, a sign of a shift in policymakers’ priorities going into 2022.

Indeed, this uptick in credit growth coincides with policy communications that emphasise supporting and stabilizing growth, particularly through moderately easier monetary and fiscal policy. On the monetary side, this has included a 50-basis point cut to the Reserve Requirement Ratio (to 10% for large banks) in mid-December, two cuts (totaling 15 basis points) to the 1-year Loan Prime Rate (LPR) since end-December, and a 10-basis point cut to the 1-year Medium-term Lending Facility rate in mid-January. Some further monetary policy easing (whether through RRR cuts, interest rate cuts, or a combination of the two) is on the table for early 2022, though it will likely remain moderate.

The PBoC’s more accommodative policy, together with a shift in the other direction for most major central banks toward tighter policy in 2022 (particularly from the Fed) should limit further CNY appreciation after a strong run in both 2020 and 2021 (+6.5% and +2.6% versus the USD, respectively). Furthermore, communication from the PBoC warning against “a one-way trade” on CNY suggests policymakers are getting uncomfortable with the extent of the currency’s appreciation, especially as it cuts into exporters’ profits. However, we don’t expect significant depreciation past 6.4 CNY per USD throughout 2022 (at 6.35 as of 19 January), as external demand is expected to remain strong and policy easing will remain moderate. Furthermore, given uncertainties related to the real estate sector in China, a stable currency could help limit market volatility, particularly related to capital outflows, suggesting policymakers may not push back too strongly against CNY strength.

Meanwhile, fiscal policy is also being used to help stabilise growth, particularly through local government bond issuance and tax cuts. Together, these measures should help year-over-year growth figures recover toward 5%, leading to 2022 annual growth of 5.1%.

India

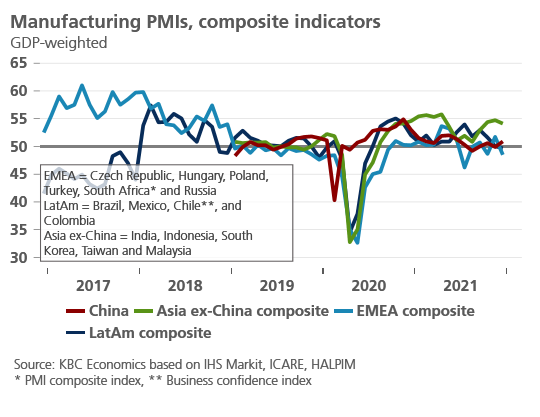

As expected, India’s economic growth rebounded 12.5% quarter-over-quarter in the third quarter after a severe Covid wave caused a sharp contraction in Q2 2021 (-11.6%). Recent data suggests that momentum may have slowed more than initially expected in the fourth quarter, with industrial production contracting 3.8% month-over-month in November. However, sentiment indicators for the manufacturing sector point to an ongoing expansion, improving to 56.3 in December from 55.7 previously. Business sentiment on the services side also remains strong at 57.3 in December. This suggests that the rebound still continued into the fourth quarter.

However, the recent surge in Omicron cases may weigh on sentiment going forward. Cases have now surged to levels last seen in June 2021, when the devastating Delta surge had finally started to ease. While mobility (for retail & recreation) has dropped off sharply since the end of December, it remains well above levels seen last spring, and workplace mobility has held up even better.

Meanwhile, India remains one of the few emerging markets where the central bank has not yet moved to raise policy rates. Though headline inflation is above the central banks 4% target at 5.6% yoy in December, the Reserve Bank of India is likely to hold off on raising rates until Q2 2022, especially given new headwinds presented by the Omicron variant. While there are, therefore, clear downside risks to the outlook, we see FY 2021 (ending March 2022) GDP growth reaching 9.2% before growth decelerates to 8.8% in FY 2022.

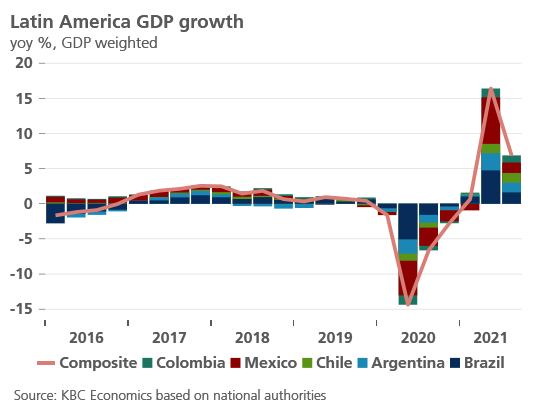

Latin America

The economic outlook for Latin America remains on fragile footing. Despite a significant improvement on the Covid front throughout the second half of the year as cases declined significantly and vaccination rates improved, activity indicators suggest only a tepid economic recovery. Though business sentiment indicators improved throughout third quarter, they have since trended down in Chile, Brazil, and Colombia, likely reflecting high producer prices and high inflationary pressures in general.

In Brazil in particular, inflation surged to a high of 10.7% year-over-year in November, before decelerating slightly to 10.1% last month on the back of lower food price inflation. Though energy prices have played an important role in pushing up headline inflation, core inflation also accelerated significantly to 7.2% year-over-year in December. With a target inflation rate of 3.5% in 2022 (vs 3.75% in 2021), the central bank increased its policy interest rate (SELIC rate) 7 times over the course of 2021, from 2.0% to 9.25%. Another 250 basis points of hikes are expected in 2022, likely frontloaded in the first quarter. Given headwinds both from the policy stance and ongoing Covid developments, real GDP growth is expected to reach only 1.0% in 2022, following recovery of 4.5% in 2021.

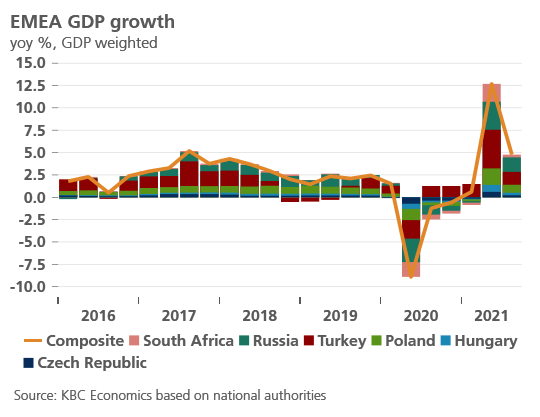

EMEA

CEE

Consumer prices also accelerated rapidly in the Central Eastern European region in the course of 2021. By the end of last year, headline inflation reached 10-year highs across regional economies, and there remains large uncertainty around the timing of a decisive easing of these strong inflationary pressures. We expect a further upward shift in the regional inflation readings in early 2022, as rising costs are passed through to prices with some delay (and not always in a symmetric manner).

The inflation spike has prompted central banks in CEE to start an unusually aggressive tightening cycle. The Czech National Bank (CNB), which has long been the most hawkish central bank in the region, has so far hiked its key rate to 3.75%, delivering a sizable 3.5 ppts of tightening between May and December 2021. In addition, the CNB’s hawkish forward guidance signals more interest rate hikes to come early this year to make sure that inflation expectations remain well anchored. We forecast the CNB will deliver another 75-bps hike at its February policy meeting, bringing the key rate to a peak of 4.5% during this cycle. Other measures taken by the CNB to anchor inflation expectations include tightening the rules for mortgage lending and increasing the countercyclical capital buffer.

The Hungarian central bank (MNB) also raised its key interest rate from 2.1% to 2.4% in December. However, the MNB is primarily using its one-week deposit rate to influence the short end of the yield curve. The one-week deposit rate has been hiked to 4% as of January 2022, after being as low as 1.75% in mid-November. The rate hikes in Hungary have also been reinforced by the ending of the central bank’s bond purchase programme. Overall, we expect that at the current stage of monetary tightening, the one-week deposit rate will peak at 4.50% at the end of Q1 2022, bringing the 3-month BUBOR to 5% (for further details on the CEE region, please see the KBC Economic Perspectives of January 2022).

Turkey

Turkey’s economy ended 2021 in the grip of another currency crisis, with the lira down more than 40% against the USD for the full year. The lira sell-off was triggered by an aggressive easing by the Turkish central bank, delivered against the background of surging headline inflation (36% yoy in December). The growing disconnect between economic fundamentals and monetary policy actions reflects strong political pressure from President Erdogan, leaving the lira exchange rate poorly anchored. With a rapid FX pass-through from the depreciating lira (estimated at around 30%) and a planned 50% hike in the minimum wage in 2022 (more than 40% of all workers in Turkey earn the minimum wage), we expect annual inflation to reach 45-50% in the first half of 2022 (also see KBC Economic Opinion of 10 January).

We see a number of possible scenarios for the Turkish economy going ahead. A significant tightening of monetary policy would represent a U-turn towards economic orthodoxy but at the cost of a sharp economic slowdown. As this appears too politically costly just 18 months ahead of elections, the Turkish government has implemented a mix of regulatory measures, particularly the new FX-linked deposit scheme. This could buy local authorities some time by stabilising the domestic currency, however, it does not address the underlying problems of the economy, i.e. the vicious circle of a weaker currency feeding into higher inflation. The longer the unorthodox experiment in Turkey lasts, the greater risk of a sharp emergency rate hike and a painful hard-landing scenario for the economy.

Russia

Activity data in Russia suggest solid momentum heading into the year-end, highlighted by a particularly strong November print for industrial production. Despite another pandemic wave, consumer demand also held up well, supported by the tightening of the labour market. Against this backdrop, headline inflation continued to surprise on the upside, reaching 8.4% yoy in December. Importantly, inflationary pressures show no signs of abating and are more broad-based than earlier in the year, prompting the Bank of Russia (CBR) to tighten its monetary policy stance further by the end of 2021.

In December, the CBR raised its key rate by another 100 bps to 8.5%, bringing it to the highest level since 2017. In addition, central bank’s commentary remained hawkish (though somewhat softer than earlier), implying that the current policy stance is still not tight enough to meet the inflation target. As a result, we expect the CBR to deliver a final 50 bps hike to 9.0% at its February policy meeting, which should mark the end of the current hiking cycle. The CBR is then expected to start easing its monetary policy from Q3 2022, assuming a notable decrease in underlying inflationary pressures.

South Africa

South Africa seems to have consistently defied the odds this year, registering a relatively robust recovery despite multiple disruptive covid waves, a weak fiscal position and significant social unrest triggered by former President Zuma beginning a prison sentence for contempt of court in July. Despite all this, GDP growth is expected to have recovered to 4.6% this year. Favourable commodity prices (especially important to South Africa are gold, platinum, and iron ore) have certainly supported this recovery, with mining activity up 9.7% year-over-year on a 12-month rolling basis through October 2021.

Inflation dynamics have also helped. Though, like elsewhere, inflation pressures have risen in South Africa, core inflation still remains below the target of 4.5% at 3.2% year-over-year as of November. This left the central bank (SARB) some room to hold off on raising the policy rate until November 2021, when it raised the rate 25 basis points to 3.75%. Compared to many other major emerging markets, this more moderate tightening path has likely supported the recovery. Further tightening is expected throughout 2022, with the SARB likely to hike 25 basis points each quarter. Together with other headwinds, including Covid and long-standing structural issues, we therefore expect growth to decelerate to 1.7% this year.

Tables and Figures

Outlook emerging market economies