Regional economic growth in Belgium

Growth rate has likely been fairly even across the three regions in 2022

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Regional growth before 2022

- 3. Regional business cycle in 2022

- 4.Estimate regional growth 2022

Click here to open PDF-version

Abstract

After Belgium's regional growth differentials became very small between 2000 and 2008, the post-war systematic growth lead of Flanders versus Wallonia and Brussels re-emerged after 2008. Between 2008 and 2021, the period from the financial crisis to the post-pandemic recovery, real gross regional product grew at an average annual rate of 1.4% in Flanders, compared to 1.1% and 0.6% per year in Wallonia and Brussels, respectively. In 2021, the latest available figure published by the Institute for National Accounts (INA) earlier this year, the economic recovery from the corona trough was stronger in Flanders (+6.2%) than in Wallonia (+4.4%) and Brussels (+5.7%). For 2022, we still lack hard figures on the extent to which economic growth (which was at 3.1% for Belgium as a whole) differed between the three regions. In this research report, we try to shed some light on this, after first briefly explaining the relative regional growth trends in the years before 2022. To estimate the regions' relative growth in 2022, we rely on regional business cycle and labour market indicators that are available for 2022 on a monthly basis.

On the one hand, the less negative consumer sentiment and better labour market dynamics in Flanders compared to Wallonia and Brussels suggest that the still well-sustained private consumption across Belgium in 2022 is mainly attributable to Flanders. On the other hand, less negative producer confidence and more favourable industrial production dynamics point to a somewhat better development on the business side in Wallonia. KBC Economics assumes that the observed contrasts in the indicators somewhat cancel each other out and that the growth differences between the three regions are unlikely to have been very large in 2022. Taking into account that private consumption was the stronghold of the 3.1% real GDP growth in 2022 across Belgium, our analysis suggests that economic growth in Flanders may have been slightly higher than in the other two regions. For final results, we will have to wait until early 2024, when the INA will publish 2022 regional growth figures.

1. Introduction

At the end of January, the Institute for National Accounts (INA) published new figures on the Regional Accounts in Belgium. These provide a picture of how the three Belgian regions (Flanders, Wallonia and Brussels) have performed relative to each other in recent years in terms of economic growth, or the growth of their 'real gross regional product'.1 These regional growth figures are only available on an annual basis (so no quarterly figures) and lag behind the publication of the national GDP figures. Meanwhile, for Belgium as a whole, we know that - at least if the preliminary flash estimate for fourth-quarter growth is confirmed - real GDP grew by 3.1% in 2022. For the three regions, the historical figures run as far as 2021 and it is not clear for now to what extent economic activity grew differently in 2022.

However, based on the already known national growth rate and regionally available business cycle and labour market indicators for 2022, we can try to make a rough estimate of regional growth last year. To put our estimated regional economic performance in 2022 in a somewhat broader perspective, we first highlight in section 2 of this research report the historical relative growth trajectory of Flanders, Wallonia and Brussels in the years before 2022. The INA provides the regional growth rates for the period 2003-2021 according to the ESA 2010 standard (European System of Accounts). As was the case for previous publications of the data, the latest publication by the INA partially revised the historical growth rates relating to this period. The older growth figures before 2003, which we show in some figures and which are based on previous accounts systems, come from KBC Economics' database. In section 3 of the report, we discuss the development of available regional business cycle and labour market indicators in 2022. That analysis allows us, in section 4, to make a first (very rough) estimate of how strong growth has been in the three regions in 2022

2. Regional growth before 2022

Flanders regains growth lead...

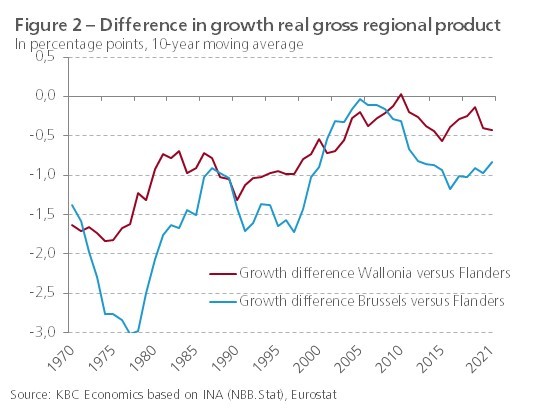

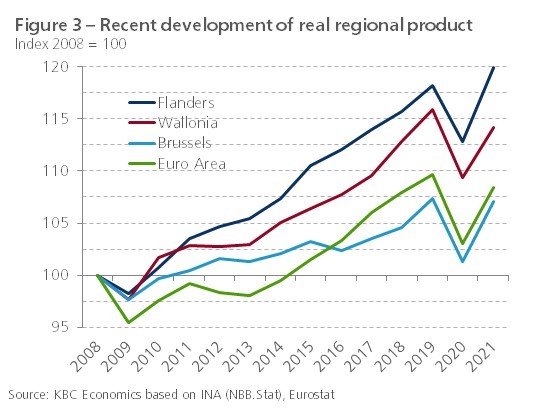

In the period between the financial crisis and the post-pandemic recovery (2008-2021), gross regional product in Flanders, Wallonia and Brussels grew at an average annual rate of 1.4%, 1.1% and 0.6% respectively in real terms (Figure 1). After Belgium's regional growth differentials had previously narrowed in 2000-2008, the systematic growth lead that Flanders recorded before 2000 compared to the other two regions thus reappeared after 2008. That the regional growth differences deepened again over the last decade is also illustrated in a slightly different way in Figure 2, which shows the growth differences of Flanders with Wallonia and Brussels per year respectively, calculated as the 10-year moving average to eliminate the large volatility in the series.

Much of the average growth differential between Flanders and Wallonia in 2008-2021 can be explained by different dynamics of economic activity during the European sovereign debt crisis in 2012-2013. Flanders then continued to grow (to a limited extent), while the Walloon economy virtually stabilised (Figure 3). The Brussels economy also continued to traipse on the spot during the European debt crisis and, moreover, had less firmly climbed out of the trough of the Great Recession in 2009. Most striking concerning Brussels, however, is its much lower average growth than Flanders and Wallonia during the period of economic recovery between 2014 and 2019. Part of the explanation lies in the terrorist attacks of 22 March 2016 at the Airport in Zaventem and in the metro in Brussels. These then hit the hospitality, retail and leisure sectors hard, resulting in negative growth in the Brussels economy that year.

More recently, the pandemic caused economic activity in Flanders (-4.5%) to contract less in 2020 than in Wallonia and Brussels (both -5.6%). The recovery in 2021 (the latest regional growth figure available) was also stronger in Flanders (+6.2%) than in Wallonia and Brussels (+4.4% and +5.7%, respectively). Consequently, activity in Flanders rose above its pre-pandemic level in 2021, while it was still lower in the two other regions (Figure 3). Flanders also outperformed the euro area (-6.1% and +5.2% in 2020 and 2021, respectively). Not only Flanders but also Wallonia performed significantly better than the euro area viewed over the entire period 2008-2021. Overall growth in economic activity over those years was 19.9% and 14.1% in Flanders and Wallonia respectively, compared with 8.4% in the euro area and 7.1% in Brussels.

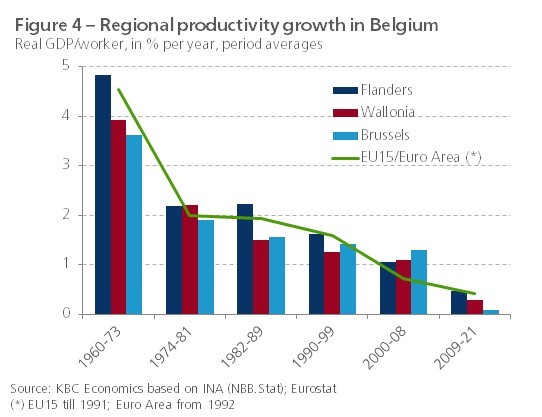

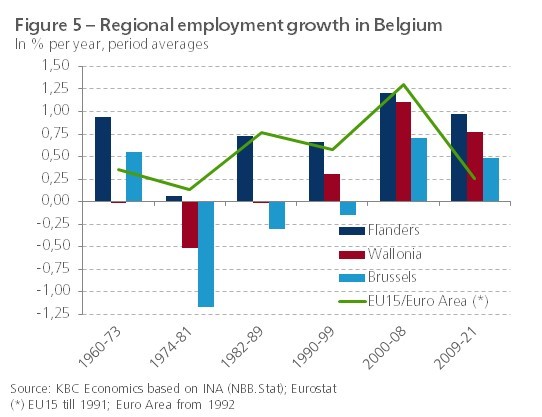

...due to higher productivity and employment growth

Simply put, economic growth is the sum of employment growth and productivity growth. The fact that Wallonia and Brussels again grew more slowly than Flanders since 2008 was primarily due to the virtual stagnation of productivity growth in both regions. In Flanders it also fell sharply, but at 0.5% a year on average it remained slightly higher than in the euro area (0.4%) (Figure 4). Employment growth was also higher in Flanders than in Wallonia (0.8%) and Brussels (0.5%), averaging 1.0% a year over the period 2008-2021 (Figure 5). Here, the three Belgian regions did score better than the euro area (0.3%). This illustrates that GDP growth has been fairly labour-intensive in Belgium over the past decade, with job creation mainly in the service sectors where labour productivity is lower than in industry.

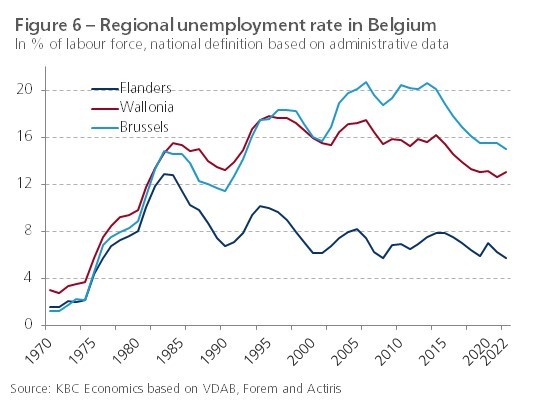

Brussels' lower average employment growth in 2008-2021 compared to the other two regions also translated into relatively worse dynamics of the unemployment rate (the share of unemployed people within the labour force) and employment rate (the share of employed people within the working-age population) (Figures 6 and 7). At least this was the case until 2014: during the 2008-2013 financial crisis, both rates deteriorated more. Remarkably, the labour market situation in Brussels has improved significantly since then, allowing the still large gap with Wallonia and especially Flanders to be reduced. Against the background of relatively weak economic growth in that region, this suggests that more and more Brussels residents have found a job outside the regional border in recent years.

3. Regional business cycle in 2022

Belgium as a whole recorded economic growth of 3.1% in 2022, a high figure that masks a large statistical spillover effect from 2021 (namely 2 percentage points). Throughout the year, however, quarter-on-quarter real GDP growth fell considerably, from still 0.6% in the first quarter to 0.1% in the last. This was due to the impact of the Ukraine and energy crises, which severely affected household and business confidence. As regional growth figures for 2022 are not yet available, we do not yet have a clear view of how the three regions have performed in relative terms in that year. To sketch out some picture of this anyway, we can rely on various business cycle and labour market indicators for which 2022 figures have already been published, even on a monthly basis.

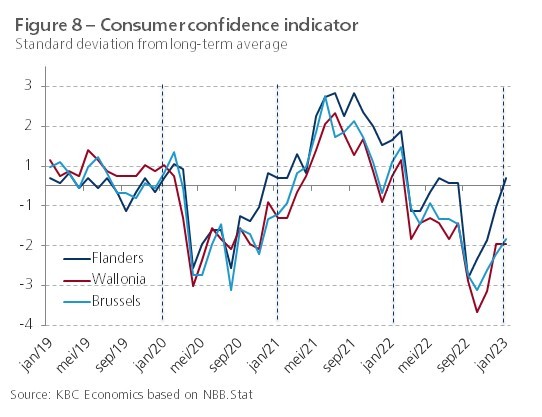

Regional sentiment indicators

Classical business cycle indicators, including consumer and producer confidence, can help gain insight into the relative course of regional economic activity in 2022 (Figures 8 and 9). Because there are significant, long-run level differences between the raw time series of the three regions, we rescaled both indicators for each region as standard deviations from the long-term average. Figure 8 shows that consumer confidence in Flanders not only climbed faster out of the pandemic trough in 2020-2021, but also continued to record higher levels than that in Wallonia and Brussels during the downturn in 2022 following Russia's invasion of Ukraine. More recently, moreover, the indicator in Flanders recovered a bit faster - as early as October - and more sharply than in the two other regions. As a result, in Flanders it was already back above its long-term average in January 2023, which was far from the case elsewhere.

The relative course of producer confidence has not mirrored that of consumers in recent years. This time, Brussels producer confidence in particular lagged during the recovery from the pandemic trough. From autumn 2021 and into 2022, producer confidence in Brussels was relatively volatile. The confidence of Flemish and Walloon companies climbed fairly evenly out of the pandemic trough, but since the end of 2021, producer confidence in Wallonia did remain above that in Flanders during the downturn. This was also the case very recently and a bottoming out of the indicator is only visible in Wallonia. Only there is the figure approaching its long-term average again. That the confidence of Flemish companies was affected more than that of Walloon companies by the Ukraine and energy crisis probably has to do with the fact that Flanders has a more open economy than Wallonia. In this sense, Flemish companies were more affected by the generally weaker growth dynamics in Europe throughout the year, as well as by the deterioration in competitiveness due to the rapid wage growth that took shape via automatic indexation.

In summary, the confidence indicators suggest that consumption demand in Flanders has held up relatively better than in Wallonia and Brussels in 2022, but that along the business side, Wallonia appears relatively less affected. Meanwhile, we already know that private consumption was the stronghold of real GDP growth across Belgium, at least until the third quarter. Its contribution to Belgium's 3.1% annual growth was 2 percentage points. Taken together, this information already points in the direction of another slightly higher economic growth in Flanders than in the other two regions in 2022.

Regional labour markets

More specifically, the relatively better consumer confidence in Flanders is also reflected in the subcomponent that gauges consumers' expectations of unemployment over the next 12 months (Figure 10). That component indicates for all three regions a sharp decline in citizens' fear of becoming unemployed since the end of 2020, but it deteriorated again after Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. In Flanders, with the exception of the more recent months, the indicator was clearly below that in Wallonia and Brussels throughout that period. The indicator on fear of unemployment is an important piece of information for estimating the precautionary savings propensity of households, and hence the course of private consumption. Likely, this propensity has been a bit lower in Flanders than in the two other regions in 2022.

We can check the course of effective unemployment in the three regions by looking at the dynamics of the number of non-working jobseekers registered with the regional employment agencies (VDAB, Forem and Actiris). Figure 11 shows the year-on-year change of that group so that seasonal effects are eliminated. During the pandemic, it peaked slightly higher in Flanders than in Wallonia in spring 2020. In Brussels, that peak fell later and was also much more limited. During the economic recovery in 2021, the number of non-working jobseekers did fall much more sharply in Flanders than in Wallonia and Brussels. In early 2022, the dynamics turned negative again in all three regions, in the wake of the Ukraine and energy crisis. In Flanders, the year-on-year change in the number of jobseekers only turned positive again in November. In Wallonia, that was already the case in May. In the whole of 2022, that number was still on average 7.3% and 2.9% lower in Flanders and Brussels respectively than in 2021, and 2.2% higher in Wallonia. By January 2023, those figures had risen to 3.4%, 10.0% and 1.5% higher than a year earlier, respectively.

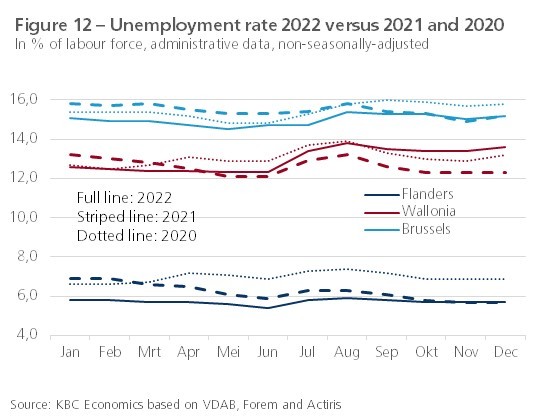

Monthly data are also available on regional unemployment rates published by the regional employment agencies (VDAB, Forem and Actiris). These are also based on non-seasonally adjusted administrative data, so we have to compare each monthly unemployment rate figure across years (Figure 12). Once again, Wallonia scored relatively worse than Flanders and Brussels in 2022. The unemployment rate there increased more strongly since the spring and has since risen above not only the corresponding monthly figures of 2021 but also those of 2020. In Flanders and Brussels, the unemployment rate towards the end of 2022 remained around that of the end of 2021 and significantly below that of the end of 2020. Figure 6, which we discussed in the first part of this report, shows the annual average unemployment rate in 2022 (using the same definition) and shows that in Wallonia it increased by 0.4 percentage points to 13.0%, while Flanders and Brussels both recorded a decrease by 0.5 percentage points to 5.7% and 15.0% respectively.

Regional industrial production

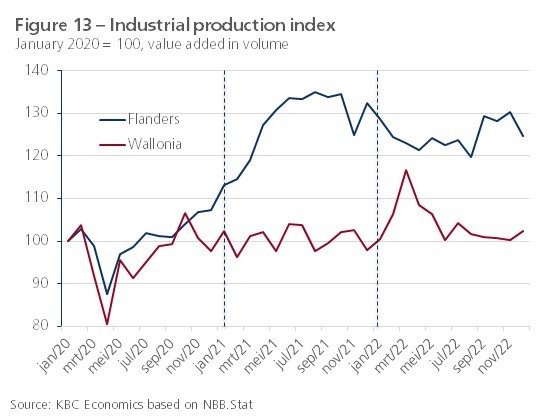

Apart from labour market figures, few 'hard' regional business cycle indicators are available on a frequent basis. Moreover, a drawback is that some, such as regional export and import figures, are only available in value terms. In periods of rising and high inflation, such as in 2022, it is then difficult to draw conclusions about the development of real economic activity. However, figures on industrial production are available for the regions in volume terms and adjusted for seasonal effects. Figure 13 shows its dynamics for Flanders and Wallonia over the past three years. In Brussels, with its typical service economy, the share of manufacturing is only a good 2% and so including that region in the analysis makes little sense.

Compared to the service sectors, industry in Belgium rebounded quickly and strongly once the economy reopened after the pandemic. The resilience of industrial activity was mainly reflected in Flemish production figures. In Wallonia, figures remained rather flat after the initial climb out of the pandemic trough. The relatively strong rebound of Flemish industry was linked to the recovery of international trade, from which Flanders was able to take full advantage. In Wallonia, the export recovery only took shape later. More specifically, especially the pharmaceutical industry recorded very good results in 2021. This branch of industry benefited from the huge demand for vaccines and their production was massively exported. This strong growth in the pharmaceutical industry originated mainly in Flanders at corona vaccine producer Pfizer.

From summer 2021, industrial activity was increasingly hampered by bottlenecks in the supply of essential inputs and staff shortages. In addition, from early 2022, the Ukraine and energy crisis hit. Especially in Flanders, this caused a major industrial downturn, with some recovery only towards the end of the year. In Wallonia, there was an exceptional peak in industrial activity in early 2022, attributable to the manufacture of IT and electronic products, which was followed by a normalisation. Throughout 2022, industrial production in Flanders was on average 2.1% lower than in 2021, while in Wallonia it was on average 3.5% higher.

4. Estimate regional growth 2022

For Belgium as a whole, real GDP growth in 2022 was at 3.1%. That this figure was still quite robust, in a context of Ukraine and energy crisis, is partly due to a large statistical carry-over effect (namely 2 percentage points). Throughout the year, quarter-on-quarter growth in Belgium as a whole did fall from 0.6% in the first quarter to 0.1% in the last. In the first quarter, investment and net exports in particular still contributed to Belgium's GDP growth, but thereafter that contribution turned negative. The fact that economic growth in Belgium still held up fairly well in the second and third quarters was due to the positive contribution of private consumption, despite the sharp drop in consumer confidence.

For the three regions, the historical growth figures only extend to 2021 and, for the time being, it is not clear to what extent growth there deviated from national real GDP growth for Belgium in 2022. The information available to estimate regional growth in 2022, discussed in the previous section, is scarce and patchy. On the one hand, the less negative consumer confidence and better labour market dynamics in Flanders compared to Wallonia and Brussels suggest that the still well-sustained private consumption in 2022 is mainly attributable to Flanders. On the other hand, less negative producer confidence and better industrial production dynamics in Wallonia point to a relatively somewhat more favourable development on the business side in that region. Given these opposing observations and the fact that regional differences in most of the indicators discussed are not huge, it remains difficult to estimate regional growth differences in 2022. Added to this is the fact that in the past, the indicators have by no means always shown a nice correlation with the eventually effectively realised growth.

We assume that the observed contrasts in the indicators discussed smooth out somewhat and that the growth differences between the three regions are unlikely to have been very large in 2022. As indicated earlier, private consumption, with a growth contribution of 2 percentage points, was the stronghold of the 3.1% GDP growth in 2022 across Belgium. Taking this fact into account, our analysis nevertheless suggests that economic growth in Flanders may have been slightly higher than in the other two regions. In concrete terms, this means that growth in Flanders on the one hand and in Wallonia and Brussels on the other will probably have been one or two tenths of a percentage point above and below, respectively, the 3.1% achieved by Belgium as a whole in 2022.

This first (admittedly very rough) estimate deviates somewhat from the Regional Economic Outlook published by the Federal Planning Bureau in mid-July 2022. At that still early date, the Planning Bureau assumed that the Ukraine and energy crisis would put a stronger brake on economic activity, with growth estimated at 2.6% for Belgium as a whole (KBC Economics also assumed a similarly lower than ultimately realised figure at the time). For Flanders, Wallonia and Brussels, the Planning Bureau then forecast growth for 2022 at 2.8%, 2.5% and 2.1% respectively. KBC Economics now assumes that growth in 2022 in the three regions was not only higher, but may have been slightly closer. For final results, we will have to wait until early 2024, when the Institute for National Accounts (INA) will publish 2022 regional growth figures.

1 Gross regional product is the gross domestic product (GDP) of a region within a country and corresponds to the total value added produced in the territory of that region.