Economic growth and jobs in Belgium: we can do better !

At present, economic growth in Belgium is slightly lower than that of the eurozone. In an international comparison, Belgium has at the same time a record number of unfilled job vacancies and a great many inactive people of working age – an age category that is also growing quite quickly. This suggests a stronger growth potential for Belgium. Compared to neighbouring countries, job creation is not at all bad, although shocking dismissals, as recently, sometimes give a different impression. But in the light of the potential, job creation is not effective enough. Better use of the potential labour supply would make forecasts for growth and employment even rosier.

Towards the end of 2017, a survey by SD Worx pointed out that three-quarters of the SMEs interviewed regards a shortage of suitable employees as the single greatest threat to economic growth in Belgium. Eurostat figures confirm that the Belgian labour market is the second tightest in the EU. Only the Czech labour market has more unfilled vacancies in proportion to supply. However, the warning was also surprising, since 6.7% of the Belgian working population was still unemployed in November 2017 (source: Eurostat). That number is substantially higher than in Germany (3.6%) and the Netherlands (4.4%). It’s true that the unemployment rate is falling, but the drop (a 2.1 percentage point since the most recent spike in the spring of 2015) is less than in both neighbouring countries and the eurozone. Neither the level of the unemployment rate, nor the speed at which it’s dropping, would suggest a tight labour market. Meanwhile, economic growth in Belgium is lagging slightly behind that of the eurozone, which is now catching up.

The paradox arises because there are two sides to the shortage issue: quantitative (how many people are available to the labour market?) and qualitative (do those people also have the competences required?). The tightness of the Belgian labour market is mainly qualitative. There is a shortage of applicants with the competences demanded in the vacancies. In a quantitative sense, there is absolutely no shortage of people who could be working. In fact, quite the contrary. There are a striking number of people of working age (often defined as being between the ages of 15 and 64) who could register in the labour market, but don’t.

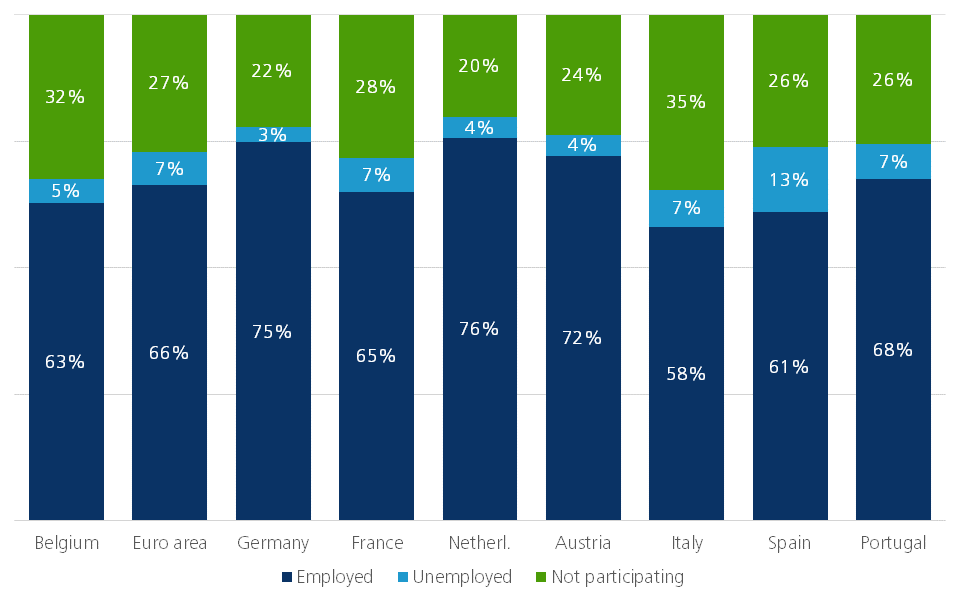

Figure 1 illustrates the fact that an unusually small section of the working population in Belgium actually had a job in the second quarter of 2017: 63% as opposed to an average of 66% in the eurozone and even 76% in the Netherlands and 75% in Germany. Of the countries shown, only Italy and Spain score more poorly. Spain’s figure reflects the aftermath of the deep recession, which caused a fierce surge in unemployment. Similar to Italy, the low employment rate in Belgium is mainly caused by the large number of people who don’t take part in the labour market. Activating them would be tapping into extra growth potential for the Belgian economy.

Figure 1 - Labour market participation of 15-64 year olds (in %, June 2017)

Source: KBC Economic Research based on Eurostat (2017)

The potential growth is even greater than Figure 1 implies. After all, Belgium’s demographic development is quite favourable. Figure 2 shows the development in the population between the ages of 15 and 64 in Belgium, neighbouring countries and the eurozone. That potential labour supply has grown by 9% in Belgium since the millennium, which is four times greater than in the eurozone. By contrast, the working population in Germany declined on balance, by almost 5% in the same period, despite the recent recovery. Migration is the strongest of the drivers. In Belgium, the steepest rise of people of working age was in the second half of the last decade. After that, the rate of the increase slowed. According to Eurostat population projections, Belgium can expect a continuing increase of around 3% until 2025, in contrast to neighbouring countries.

Figure 2 - Population between the ages of 15 to 64 (2000 = 100)

Source: KBC Economic Research based on Eurostat (2017)

This reasonably significant increase implies a relatively high potential economic growth, if those people also carry out productive work. The rise in the employment rate could act as a lever on the underlying demographic growth stimulus. However, this calls for substantial job creation: it’s not just a case of creating jobs for the ‘existing’ inactive individuals in the 15-64 age group, but also for the growth of that group. Meanwhile, the economy is constantly changing. Jobs are disappearing, sometimes massively, as recently, which means that affected people have to look for a new job.

How well does the Belgian labour market perform in terms of job creation? The growth in job creation is not bad at all, compared to that of neighbouring countries and the eurozone average. There are almost 7% more people in work since the first quarter of 2008 (Figure 3). That growth is clearly higher than the eurozone average (+ 4.9%) and much higher than that of France and the Netherlands (+ 2.6%), even though several EU countries are now starting to catch up. Germany is most successful, with an increase of almost 9%. Due to the relatively strong population growth, the increase in employment in Belgium nevertheless causes less of a rise in the employment rate, and the drop in the unemployment rate is also less strong. By only considering those indicators, the labour market performance is somewhat underestimated.

Figure 3 - Domestic employment (in persons, Q1 2008 = 100)

Source: KBC Economic Research based on Eurostat (2017)

Creating jobs is good, but creating productive jobs is better. Maintaining the level of productivity growth is a major challenge. That brings us back to the qualitative aspect of the labour market shortage: better labour supply will lead to better jobs, which, in turn, will lead to a greater contribution to productivity and the creation of wealth. Provided such an improvement in quality takes place, and the demographic potential growth is utilised, the growth and employment forecasts for the Belgian economy look a lot stronger than current expectations.