Economic review on the annus horribilis in the euro area

The economic figures for the annus horribilis 2020 are gradually being completed. It has been pointed out several times that the Covid-19 crisis hit the European economies harder than the other major economies, such as in the US and especially China. There were also significant differences between the European countries themselves. But there were also similarities. These can now be illustrated by the impact over the whole year 2020 on the components of spending, on added value and on employment in the major economic sectors. A comparison of the six largest euro area countries shows that, on an annual basis, the fall in private consumption was the main contributor to the economic contraction everywhere. This illustrates the atypical character of this recession, as consumption is usually a stabilising factor. The comparison also shows that the economic downturn in Spain, the country most affected, was almost three times greater than in the Netherlands, the country least affected. Italy also experienced a relatively sharp economic decline. The differences are mainly explained by the size of the contribution of private consumption to the contraction. They result from structural economic differences. The southern European economies are more dependent on household consumption than the others. Moreover, the sectors that were strongly affected by the measures to combat the pandemic have a relatively large economic importance there. These are sectors such as trade, transport and hospitality (which are the main subsectors of tourism), arts, entertainment and recreation. This not only increased the direct negative economic impact of the pandemic through these sectors. It probably also caused a greater negative shock to household income. This contributed to a greater decline in their other consumption expenditures. The stronger than average economic contraction in France, meanwhile, was mainly due to the relatively large negative growth contribution of investments and public consumption. In Germany, in contrast, public consumption contributed to the relatively limited economic contraction. In Belgium, the strong decline in private consumption and the relatively large negative contribution of investments were the main cause of the GDP contraction.

Household expenditure biggest factor in contraction

Figure 1 shows the percentage decline in GDP in 2020 compared to 2019 for the euro area as a whole and for the six largest euro area countries, as well as the contribution of each expenditure component. Firstly, the large differences within the euro area regarding the economic downturn in the annus horribilis are striking. Real GDP in the euro area in 2020 was 6.8% lower than in 2019, but in the Netherlands the fall was 'only' 3.8%, while in Spain it was almost three times as big at 11%. In Belgium, the contraction was 6.3%, slightly less severe than the eurozone average.

Secondly, it is worth noting that private consumption was the main contributor to the economic contraction in all the countries considered. This does not mean that household consumption expenditure experienced the largest decline of all spending components. In the countries under consideration, this was only the case in Belgium. However, private consumption is the largest expenditure component in absolute terms, which means that its fall has a greater impact on the fall in GDP. The share of private consumption in GDP is highest in Spain and Italy. It amounted to 57.3% and 60% respectively in 2019, compared to an average of only 53.4% in the euro area as a whole and 51.4% in Belgium. The particularly large contribution of private consumption to the fall in Spanish and Italian GDP is therefore the result of both the sharp contraction in household consumption expenditure and its large share in GDP.

For the euro area as a whole, the fall in investment demand was similar in magnitude to that of private consumption (-8.5% versus -8.1%), with large differences between countries nonetheless. The smaller share of investment in GDP meant that its negative contribution tended to be more limited. After Spain, the fall in investment was greatest in France, which traditionally has a relatively high investment ratio. This explains why investments made a relatively large negative contribution to growth. In Belgium, the high investment ratio explains the rather large negative contribution of investment to the contraction of GDP.

The strongest declining expenditure component was exports of goods and services. However, their negative impact on the fall in GDP was limited by the fact that imports also fell sharply.

Despite the massive use of budget support for the economy, only in a few countries did public consumption make a direct - albeit very limited - positive contribution to economic growth. Indeed, the main focus of public support has been on income transfers to households and businesses and much less on an increase in public consumption. According to IMF data, the additional spending on health, for instance, represented only 8% (Italy and France) to 12% (the Netherlands) of the additional fiscal measures (excluding the so-called 'automatic stabilisers') that governments allocated to the fight against the pandemic in 2020. With a share of 18%, Belgium was an outlier. In addition, the direct impact of the lockdowns also plays a role. In France, for instance, government services were also closed during the first lockdowns, which contributed to the fact that in France, government consumption in volume terms for the entire year was significantly lower than in 2019 and that the negative growth contribution of government consumption is relatively large there. Together with the relatively large negative growth contribution of investment, this explains the rather sharp decline in French GDP, despite a rather average negative growth contribution of private consumption.

Consumption differences between countries...

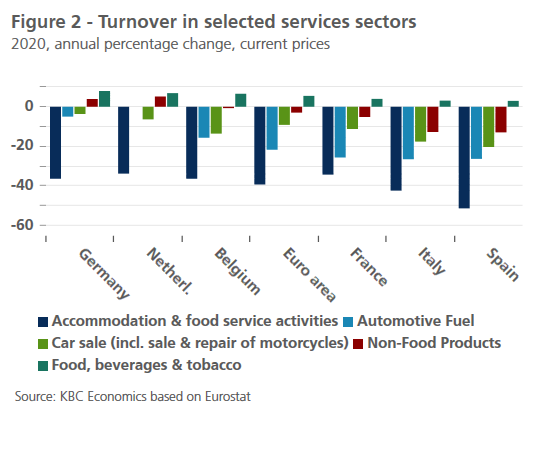

The decline in household consumption was the main cause of the economic contraction in all countries considered. But the decline was not the same in every country and for most countries these differences largely explain the differences in the overall economic impact of the pandemic. Figure 2 summarises some detailed figures on retail sales and data on sales in some other sectors. This allows for a sharper picture of the impact of the pandemic on household spending. There are both similarities and important differences.

Box 1 – Atypical recession

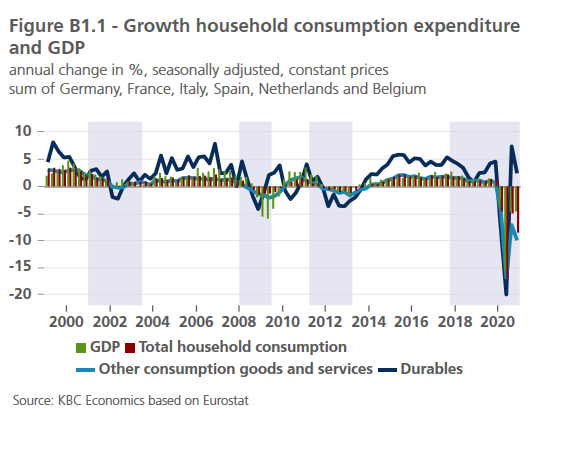

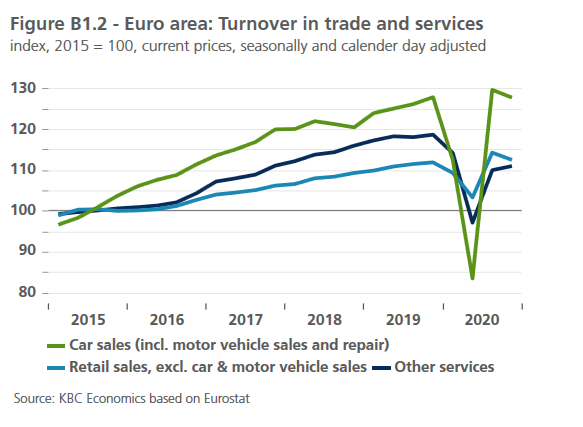

The fact that household spending made the largest contribution to the economic contraction underlines the atypical character of this recession. Usually, consumption expenditure fluctuates less than total GDP and is thus a stabilising factor during recessions. This is true at least for non-durable consumption, which accounts for over two-thirds of total household consumption. The purchase of durable consumer goods is usually less urgent and can therefore be more easily postponed during economic downturns. As a result, these purchases tend to fall more sharply than GDP during recessions and grow more strongly during boom periods.Figure B1.1 illustrates that this rule of thumb did not hold in 2020. While purchases of durable consumer goods fell, as expected, somewhat more than other consumption (and more than GDP) during the lockdowns of the first wave of the pandemic, a remarkably quick and strong recovery followed afterwards. Even in the fourth quarter of 2020, when the economy was again plagued by lockdowns, purchases of consumer durables held up reasonably well. Against the peak purchases of the third quarter, there was only a decline of less than 5% (by volume) and compared to the fourth quarter of 2019, purchases were even 2.4% higher. Figure B1.2 illustrates for the whole euro area that car sales played an important role in this. In the second half of 2020, sales (at current prices) of cars (including motorcycle sales and repairs) recovered strongly from the sharp drop in the spring. In the fourth quarter of 2020, it was comparable to the peak sales level of a year earlier. However, it was almost 10% lower than in 2019 for the whole of 2020. This is significantly more than the decline in annual turnover in other retail trade, which was limited to just over 1%. It is also a larger drop in turnover than in the other service sectors (which also include services to companies), which amounted to around 8.5% for the whole of 2020. However, if we compare the fourth quarter of 2020 with the fourth quarter of 2019, these other services were the most severely affected by the pandemic. Turnover there was still 6.5% lower.

It is clear that the hospitality sector was hit hardest everywhere, with decreases from around 35% in France and the Netherlands to over 50% in Spain. In all countries, the flip side of that decline was an increase in sales of food, beverages and tobacco, with those sales higher by 3% (in Spain) to 8% (in Germany) in 2020 than in 2019. Car sales have also declined in all the countries considered, but here the differences between the countries are much greater. With a drop in sales of more than 20%, car dealers (including motorcycle dealers and repairers) were hit hardest in Spain, while in Germany (-3.7%) they held up reasonably well on balance. In Belgium, turnover in car sales fell relatively sharply. There are also strikingly large differences between countries in motor fuel sales . The small decline suggests that mobility was less restricted in Germany than in the other countries. This is also evident from Google's mobility data. Nevertheless, the most striking differences are to be found in the turnover of non-food products (excluding fuels). Spain and Italy experienced a steep decline of 13%, while the Netherlands and Germany still recorded growth of 4% to 5%.

...resulting from differences in the income shock...

The different spending patterns may be related to the nature and follow-up of the lockdown measures and mobility restrictions, but also suggest a different impact of the crisis on household incomes. Full year figures are not yet available on this, but Eurostat figures for the first three quarters of 2020 show that in Spain, Italy and France (nominal) household disposable income fell by 11.6%, 9.6% and 9.3% respectively compared to the previous year, while in Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands, increases of 1.3%, 1.5% and even 3.8%, respectively, were still recorded.

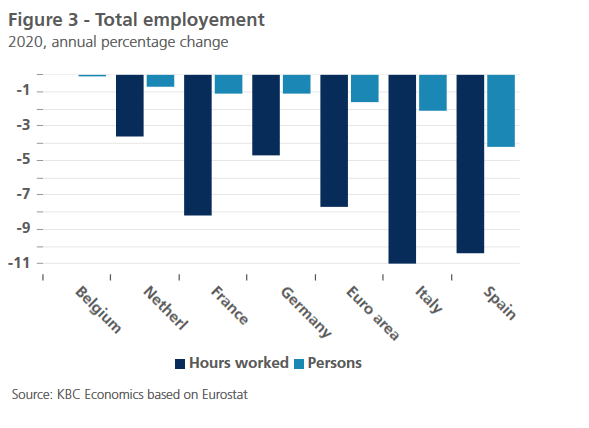

European Commission estimates for the whole year 2020 suggest that wage income of employees and the income of the self-employed have fallen everywhere, but significantly more in Southern Europe. This estimate is confirmed by the figures on employment and the volume of hours worked in 2020 (Figure 3). Compared to the fall in GDP, job losses have been limited (for the time being). Nevertheless, in 2020 there were already more than 4% fewer people in employment in Spain than in 2019. This is the largest decline in the countries considered, followed by Italy (-2.1%). However, the decline in the number of hours worked was more in line with the sharp contraction in GDP and therefore much larger than the job loss. This suggests that the income shock was also much larger than the job loss would suggest. Again, the fall was most severe in Spain and Italy. It confirms the European Commission's estimates that labour income losses were greater in Southern Europe than elsewhere in the eurozone. The European Commission's estimates also indicate that government income compensation has remained comparatively much more limited there.

... reflecting structural differences

That relatively large income shock reflects the relatively large share of sectors that were heavily affected by the lockdown measures, such as trade, transport and hospitality. These sectors represented 23.5% of value added and almost 30% of employment in Spain in 2019. The arts, entertainment and leisure sectors, which were also badly affected, accounted for a further 8.6% of employment in Spain (Figure 4). At 36.4%, the share of these sectors in employment is also significantly higher in Italy than in the other major euro countries.

The impact of the pandemic on consumption is already higher in the southern European countries because catering and transport expenditure, which are directly affected by the measures taken to combat the pandemic, have a relatively high importance in household consumption. But this relatively large direct economic impact is, more than in the other countries, reinforced by the fact that these structural differences increase the income shock. This also affects other consumption expenditures more.

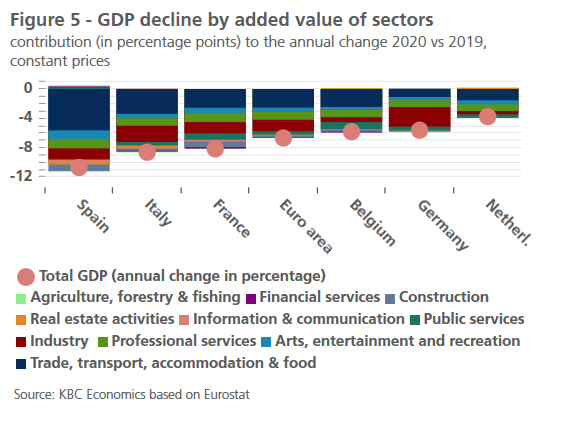

Structural differences are also reflected in the breakdown of the economic contraction according to value added by sector. On average in the euro area, about 40% of the decline occurred in the trade, transport and hotel sectors (Figure 5). However, in hard-hit Spain this was more than half. Moreover, in Spain the arts, entertainment and recreation sectors also contributed 1.2 percentage points to the GDP contraction, double the euro area average. Italy follows in second place.

The construction sector also made the largest contribution to the decline in Spain of all countries considered, followed by France. This is related to the relatively large negative contribution of investment demand to the GDP contraction in both countries, but also to the relatively large weight of the construction sector in both economies. In Germany, the relatively high resilience of mobility and turnover in the hotel and catering industry and especially in retail trade is logically reflected in the rather low contribution of the decline of value added of the trade, transport and hotel and catering sectors.

It is not only because of this that the breakdown of the coronavirus recession in Germany as seen in Figure 5 looks somewhat different from that in the other major euro countries. The fact that manufacturing accounts for almost half of the contraction in German GDP also contributes to that image.

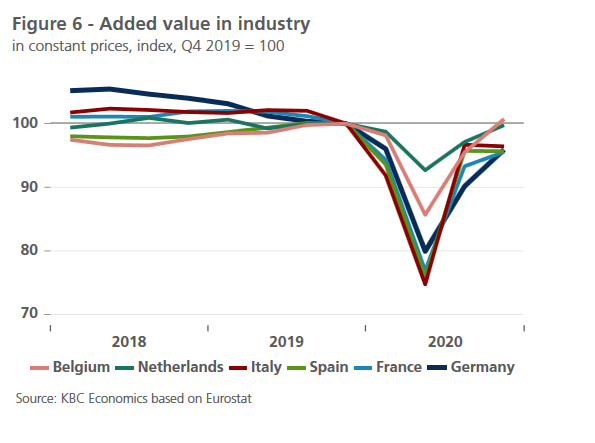

Nevertheless, German industry has not been particularly hard hit by the Covid crisis. Figure 6 shows that after the first wave of the pandemic, the drop in added value was less severe than in France, Spain and Italy. In the third quarter, Germany did experience a less strong recovery, but in the fourth quarter, value added compared to the pre-pandemic level, was on a par with France, Spain and Italy. The Belgian and Dutch industries were in an even better position compared to pre-pandemic. The relative resilience of industry is an important reason why the economic downturn in both countries remained smaller than the eurozone average.

The relatively large contribution of industry to the contraction of overall German GDP is therefore mainly explained by the greater importance of industry in the German economy (21.9% in 2019, compared to 17.6% in Italy and 12% in France). Moreover, in 2020, German industry had to cope not only with the Covid-19 shock but also with the after-effects of the recession in which it had been caught since the second half of 2018. The problems in the automotive sector, which makes up a very large part of German industry, play an important role in this. The recovery from the coronavirus shock was similar in German industry at the end of 2020 to the recovery in the other major euro countries, but a comparison with 2019 and especially 2018 shows that the recovery of German industry is still far from complete.