Economic Perspectives March 2022

Read the full publication below or click here to open the PDF.

- The Russian invasion of Ukraine has fundamentally altered the global geopolitical landscape, with significant consequences for the economy and financial markets. While there is still significant uncertainty as to how, and for how long, the conflict will play out, the war itself, together with severe sanctions imposed by Western economies on Russia, has led to a marked risk-off sentiment shift in financial markets, a surge in energy and other commodity prices, and an abrupt, severe isolation of the Russian economy.

- The surge in energy prices reflects Russia’s role as the world’s second largest producer and exporter of oil and a crucial source for EU gas imports. Concerns that supply could be severely disrupted through embargos imposed by the West or a retaliatory decision by Russia, together with businesses eschewing Russian oil due to reputational risk and uncertainty, are contributing factors to the jump in prices. The situation remains highly uncertain, and there is a non-negligible risk of energy shortages in the EU. Given the current situation, we upgraded our Brent oil outlook to 130 USD/barrel for the end of Q1 2022 and 90 USD/barrel at the end of the year. But risks are clearly to the upside.

- The further increase in commodity prices, and particularly energy prices, will add upward pressure – and for longer – to already elevated inflation in both the euro area and the US. As such, we have meaningfully upgraded our outlook for average headline inflation in the euro area from 3.6% to 5.5% in 2022 and from 1.6% to 2.2% in 2023. For the US, we have upgraded 2022 headline inflation from 4.2% to 5.8%.

- The war in Ukraine and the related sanctions on Russia are expected to have a negative impact on euro area growth, mainly through the energy price channel, which will weigh on consumer purchasing power and business sentiment. There may be some mitigating factors, such as increased fiscal spending, but the impact will likely be gradual. We have downgraded our growth outlook for this year from 3.5% to 2.7%, and for 2023 from 2.4% to 2.1%.

- The US economy continues to show signs of a strong recovery with the labour market adding 678,000 jobs in February as the covid situation improved significantly. Though US economic activity is less directly exposed to developments in Ukraine, higher energy prices and the resulting inflationary pressures could weigh on consumer sentiment and consumption. As such, we have downgraded US GDP growth from 3.3% to 3.1% in 2022 while leaving growth unchanged at 2.3% in 2023.

- As the war in Ukraine and the resulting energy shock are expected to, in general, increase inflation and lower growth, the path of policy normalisation for major central banks has become slightly more complicated. However, in line with our expectations, the ECB has outlined a faster wind-down of its Asset Purchase Programme, contingent on incoming data not materially deteriorating. We continue to expect a first rate hike by the end of 2022. For the Fed, we maintain our outlook of five 25 basis point rate increases this year, starting in March, followed by four in 2023. Meanwhile, the recent depreciation of the Czech koruna and Hungarian forint have triggered further policy tightening from the CNB and NBH.

War reshapes the global outlook

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has fundamentally altered the global geopolitical landscape, with significant consequences for the economy and financial markets. The war itself, together with severe sanctions imposed by Western economies on Russia, has led to a marked risk-off sentiment shift in financial markets, a surge in energy and other commodity prices, and an abrupt, severe isolation of the Russian economy. While there is still significant uncertainty as to how, and for how long, the conflict will play out, the surge in energy prices will keep inflation higher for longer, and particularly for European economies, will weigh on both consumer purchasing power and business sentiment. Furthermore, the risk of further disruptions to European oil and gas supply, and therefore to economic activity, remains elevated.

Energy markets react

Russia’s decision to invade Ukraine has had an immediate impact on financial markets, with the surge in energy prices being the most notable, and from a global economic perspective, the most consequential. Oil prices had already been increasing steadily since the beginning of this year as inventories dwindled and geopolitical risks rose in the lead up to the invasion. Brent crude prices then surged more than 25% relative to mid-February to levels not seen since 2012. Gas prices (Dutch TTF) also surged from 70 EUR/Mwh at the start of the year to over 226 EUR/Mwh on 7 March 2022 (figure 1). Energy prices remain elevated though they have partially retraced from these highs, and the situation remains highly volatile.

While there are a number of factors at play, the price surge reflects Russia’s role as the second largest producer and exporter of oil and a crucial source for EU gas imports. Concerns that there could be a major disruption of energy supply coming from Russia, whether due to embargos from Western countries or from Russia deciding to cut off supply as a counter measure, have been a major driver of the upward move in prices (i.e., the higher prices partially reflect a higher risk premium). On top of that, in the days since sanctions were announced (see Box on page 3: Sanctions and corporate boycotts isolate the Russian economy for details), it has become increasingly difficult for Russia to find buyers for its crude oil. In effect, banks, shipping companies, refineries, etc. are steering clear of Russian oil whether due to uncertainty about the imposed sanctions or due to concerns over reputational risk. This so-called “self-sanctioning” is notably happening despite EU-policymakers’ clear intention to carve out oil and gas from the sanctions and leave a channel for payments in energy trade to continue.

Hence, the energy market remains in a highly fluid situation with substantial upside risk stemming from a further possible disruption to supply, but also with some downside potential. Beyond the above-mentioned factors, the possible release of further IEA strategic petroleum reserves (60 million barrels were announced March 1), efforts to revive the nuclear deal with Iran or lift US sanctions on Venezuelan oil, future OPEC decisions, and developments in US shale production could impact the oil price trajectory going forward. Given the substantial uncertainty around the trajectory of the war, however, risks remain skewed to the upside. We have revised up our near-term oil forecast to 130 USD/barrel for Q1 2022 and anticipate a higher end-year price of 90 USD/barrel. Longer term, the crisis raises important questions about Europe’s energy security and dependence on Russian gas imports, and about the green energy transition.

Box 1 - Sanctions and corporate boycotts isolate the Russian economy

The US and EU, together with other nations, have responded to the Russian invasion of Ukraine with swift and substantial sanctions on the Russian economy, as well as on Russian politicians, officials, and oligarchs. These sanctions build on ones already in place since 2014 but are much more severe and effectively have resulted in an abrupt isolation of Russia from many aspects of the global financial system.

A significant focus of the sanctions is centred on isolating Russian financial institutions by freezing bank assets, blocking transactions in USD, prohibiting access to international capital markets, and excluding a number of Russian banks from the SWIFT international payment system. Exclusion from SWIFT makes it significantly harder for Russian banks to make and receive international payments, thereby impeding international trade. Trade restrictions and sanctions imposed on certain non-financial institutions (particularly state-owned enterprises) have been relatively targeted, focusing on advanced technologies, the aerospace sector, and goods with potential military use.

Notably, the financial sanctions and trade sanctions have so far purposefully left channels open for Russian trade in gas and oil products with the EU to continue. However, the oil and gas sector has not been completely shielded from the sanctions, with Germany halting the certification of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, and the US and UK banning the import of Russian oil. Furthermore, even without direct sanctions, many businesses, from banks, to insurance companies to refineries, are avoiding Russian oil due uncertainty and reputational risk. This form of corporate self-sanctioning, or corporate boycotting, is happening within other sectors as well, with a myriad of international companies suspending operations in Russia.

Furthermore, the Russian central bank has been targeted with sanctions by the US, UK, and euro area countries, effectively freezing the central bank’s reserve assets held in USD, GBP, and EUR. Of Russia’s USD 630 bn in foreign exchange reserves, roughly 20% is held in gold, and 74% is held in foreign currency. Though the exact breakdown of those foreign currency reserves is not available, globally, 55% of reserves are held in US dollars, 20% in euros and 4% in pound sterling. Though Russia has diversified its holdings toward Chinese assets in recent years (reportedly around 20% of its reserves), a significant share of Russia’s reserves (likely around 50%) have been rendered useless by the central bank sanctions. This makes it far more difficult for Russia to evade sanctions targeting international payments or for the central bank to intervene to support the Russian rouble.

Indeed, the RUB has been in freefall since mid-February, losing 38% of its value versus the USD. With a suddenly limited toolbox, the Russian central bank hiked its policy rate from 9.5% to 20% on 28 February. However, the tightening seems to have had hardly any impact on stabilising the currency, which is unsurprising given the vast uncertainty surrounding the current situation and the magnitude of the measures targeting Russia’s economy. Indeed, the extent to which the sanctions, together with corporate boycotting, will squeeze the Russian economy is difficult to assess at this time. However, historic examples of countries being excluded from the international financial system (and generally in a less severe manner) suggest that economic activity will take a major hit, inflation will accelerate significantly, and the risk of a sovereign debt default will grow.

Even more persistent inflation

The further increase in commodity prices, and particularly energy prices, will add upward pressure to already elevated inflation, particularly in the euro area. The February reading for euro area inflation surprised to the upside at 5.8% yoy, while core inflation accelerated to 2.7% yoy from 2.3% in January (figure 2). Throughout 2021 and early 2022, high energy prices and global supply bottlenecks were the main drivers of inflationary pressures, and those drivers were previously expected to ease in the coming months. While headline and core inflation are still expected to decline over 2022, the recent upward move in energy prices means that the peak is now likely to be much later than so far envisaged. As a result, headline inflation in particular will remain higher in the coming months. Furthermore, although there were tentative signs in January and February – according to the Fed’s new Global Supply Chain Pressure Index – that supply chain disruptions were finally starting to ease, recent developments may cause further disruptions through shortages of certain inputs coming from Russia or Ukraine (e.g., palladium and neon gas, both of which are used in the auto industry).

As such, we have meaningfully upgraded our outlook for average inflation in the euro area from 3.6% to 5.5% in 2022 and from 1.6% to 2.2% in 2023. Furthermore, the elevated-for-longer headline inflation outlook adds upside risk to core inflation as well, as defensive positioning from firms and mark-ups could begin to creep into the core inflation figures. Though it is not part of our baseline scenario, the possibility that higher energy prices, and particularly gas prices, could persist into next year if supply were to remain disrupted adds further upside risk to the inflation outlook.

While the US market is less directly exposed to supply disruptions from Russia, higher oil prices will also have an impact on US inflation. In February, US inflation reached 7.9%, driven by higher food prices, energy costs, and rents. The latter helped drive core inflation, which also accelerated to 6.4% (figure 3). Given the upward revision to our oil price outlook, we have also revised up US headline inflation from 4.2% to 5.8% in 2022.

Inflation to weigh on euro area activity

Though the latest covid wave is fast receding and hope is emerging that the ongoing reopening of economies will be more permanent, a new crisis with headwinds to European growth has appeared. The war in Ukraine is expected to have a negative impact on euro area growth, mainly through the energy price channel. In particular, higher energy and commodity prices will weigh on consumer purchasing power and business sentiment and may also constitute additional cost push shocks. There will be some impact via trade channels with Russia, though direct trade links outside of the energy sector are relatively limited on average. Finally, unintended spill-over effects from the sanctions imposed on the financial sector to the real economy (e.g., in the form of financial frictions or uncertainty about payments in a globally interconnected business landscape) may slow international trade and weigh on production.

At the same time, there may be some mitigating factors, such as efforts at the EU level to address the energy price shock, increased fiscal spending on military and government initiatives, and the cushion from still elevated savings that will likely be deployed as daily covid cases and hospitalisations continue to ease. It is also possible that infrastructure investment to fast track the EU’s energy transition (with a more urgent focus on reducing energy dependence on Russian oil and gas) could increase. However, the extent of such mitigating fiscal factors is not yet clear, and any impact will likely be gradual. We therefore expect the biggest negative shock to growth to occur in Q2 2022, and we have downgraded our growth outlook for the year by 0.8 percentage points to 2.7%. For 2023 we have downgraded the growth outlook more modestly from 2.4% to 2.1%. Risks remain titled to the downside, particularly in the case of further disruptions to oil or gas supply.

US growth outlook

US economic activity is less directly exposed to developments in Ukraine and the severe sanctions imposed on Russia. However, higher energy prices and the resulting inflationary pressures could weigh on consumer sentiment and consumption in the US as well, especially as price pressures in the US have so far been broader based than in Europe.

Aside from the current geopolitical context, the US economy continues to show signs of a strong recovery. Business sentiment in the manufacturing sector (as measured by the ISM) improved to 58.6 in February from 57.6 the month prior thanks to an improvement in the new orders component of the survey. Furthermore, the labour market continues its stellar recovery, with 678,000 net jobs created in February – a strong acceleration from the 481,000 created in January. In part, this reflects the easing in the number of daily covid cases to levels not seen since last summer, with the leisure and hospitality sector accounting for 26% of jobs created in February. Despite these positive developments, given the recent energy price shock, we have downgraded US GDP growth from 3.3% to 3.1% in 2022 while leaving growth unchanged at 2.3% in 2023.

China plays its role

Limited economic data is available for the Chinese economy so far in 2022 aside from business sentiment indicators that point to a modest improvement from January to February and preliminary trade data that show a deceleration in both imports and exports in February. Meanwhile, the government announced that its growth target for 2022 is set at 5.5%, which is lower than past years but will still be difficult to achieve given headwinds coming from the real estate and construction sectors.

While Russia’s decision to invade Ukraine does raise important geopolitical considerations for China, the economic implications are less than clear. With the US, EU and other countries imposing severe sanctions on Russia’s economy, this carves out a path for China and Russia to deepen their financial and economic ties. While this would be in line with China’s long-term goal of internationalising its currency, for example, the benefits to China of pursuing this path are tempered by the severe economic situation facing Russia. While the direct economic impacts are likely limited, given higher commodity prices and the downgrade to global growth prospects, we have modestly revised down Chinese GDP growth from 5.1% to 5.0% for 2022.

Clouding the central bank outlook

As the war in Ukraine and the resulting energy shock are expected to, in general, increase inflation and lower growth, the path of policy normalisation for major central banks has become slightly more complicated in recent weeks. This is particularly true for the ECB, as the euro area recovery lags behind that of the US while the factors that have driven inflation higher so far should generally be seen as temporary (i.e., energy prices and supply disruptions). However, with headline inflation now well above the ECB target, core inflation trending up again in February, and recent developments likely to send headline inflation even higher, there remains significant pressure on the ECB to act sooner rather than later.

This dilemma was made clear after the ECB’s March policy meeting, where the guidance for the wind-down of the Asset Purchase Programme (APP) was accelerated slightly, but it was also noted that end of the APP in Q3 2022 is contingent on the data supporting “the expectation that the medium-term inflation outlook will not weaken”. This is in line with our expectation for the ECB to end the APP at the end of Q3 2022 and to hike the deposit rate 25 basis points in Q4 2022, followed by further policy normalisation in 2023.

While the Fed must also weigh the diverging impact that the war in Ukraine will have on US growth and inflation, the stage is more clearly set for the Fed to kick off its hiking cycle at its March meeting next week. Inflationary pressures, while still driven significantly by energy prices, are more broad-based than in the euro area and the recovery in the labour market has been robust. Average hourly earnings grew 5.1% yoy in February, down slightly from January (5.5% yoy) but still elevated relative to pre-covid rates (2017-2019 average: 3.1% yoy). However, real average hourly earnings have been declining since the beginning of 2021, suggesting that while high inflation in the US may contribute to higher wages, it is also eating into household purchasing power.

Recent comments by Fed Chair Powell confirm that a first rate hike of at least 25 basis points can be expected at the upcoming March meeting. We therefore maintain our outlook of five 25 basis point rate increases this year (starting in March), followed by four in 2023. A faster normalisation, for example with 50 basis point rate hikes, however, is not out of the question. We also still expect balance sheet normalisation to start in June, with some guidance as to the timing and details coming at the March meeting.

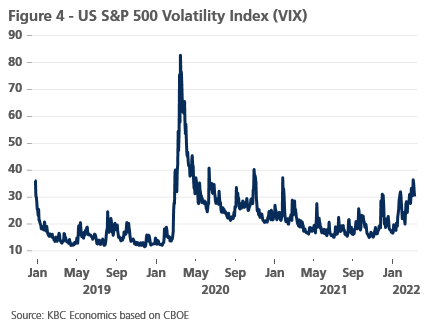

Finally, uncertainty surrounding the war and the impact that sanctions may have on energy markets and broader financial stability will likely lead to increased volatility in financial markets for some time. Volatility as measured by the VIX has increased sharply since mid-February, but notably remains below levels seen in early 2021, and well below the height reached at the outset of the pandemic in March 2020 (figure 4). This suggests that while risks are heightened, financial instability for now remains limited.

All historical quotes/prices, statistics and charts are up to date, through 9 March 2022, unless otherwise stated. The positions and forecasts provided are those of 9 March 2022.