Economic perspectives March 2020

Read the full publication below or click here to open the PDF.

- The corona-virus (covid-19) has caused major disruption and dislocation to the global economy. We expect a widespread recession in Europe as well as in the US due to the pandemic. Policy responses to the corona crisis are fast and far-reaching and are likely to mitigate the lasting impact of the crisis as well as to assist the speed of the recovery. In particular, monetary authorities are adopting markedly more accommodative policy measures. On top of that, many governments have already announced substantial fiscal stimulus. Therefore we expect that the corona crisis will cause a deep, but temporary global recession. By the end of 2020 and through 2021 a gradual recovery is expected while the long-term outlook for the global economy is maintained. In this publication we present a scenario that takes into account recent developments in so far as this is possible. However, as circumstances are changing rapidly and uncertainty is high, these forecasts are likely to require regular updates. Risks remain clearly to the downside, unfortunately, despite the fact that our new economic scenario contains a much weaker economic outlook than our previous scenario.

- We expect an internationally synchronized deterioration in the business cycle. Nevertheless, the magnitude of the corona recession is likely to differ across countries. The latter will depend on the importance of tourism, the integration of countries in European and global production chains, the availability and quality of medical services, each economy’s recent growth momentum and the available budgetary space to mitigate the economic impact.

- The corona crisis will also cause some dampening effects on inflation rates since global demand will fall. However, the price war on oil markets between Saudi Arabia and Russia will have a greater downward impact on inflation expectations in the euro zone. The lower oil price is expected to have a temporary positive impact on European growth as it will provide a marginal offset to the negative corona effects.

- Central banks have already taken drastic measures to provide substantial support to contain the recession due to the corona crisis. In particular the Fed anticipated the corona crisis’ economic impact by cutting the policy rate twice and drastically, first by 50 bps and then by another 100 bps. As the ECB policy rate is already significantly in negative territory, the ECB announced no further rate cuts. However, both the Fed and ECB have announced substantial measures in terms of liquidity provision and additional quantitative easing. Other central banks across the world are implementing similar policy changes. We expect central banks to take further action as needed. Further interest rate cuts by the ECB and Fed are unlikely at the moment, but significant further unconventional policy initiatives may be required in response to an unprecedented and still evolving corona crisis.

- The corona crisis and the shock in the oil market have caused a sharp risk-off wave in financial markets. As a result of a widespread global flight into safe havens in combination with expectations of more accommodative monetary policies, long-term government bond yields dropped substantially and are expected to stay low. However, those same risk-off drivers coupled with expectations of potentially huge fiscal initiatives have caused yields to bounce off their lowest levels and spreads between countries to widen notably. These influences are likely to remain a source of significant volatility in interest rate markets in the current environment.

Pandemics versus economics

The corona (covid-19) pandemic is first and foremost a health problem, and undoubtedly a human tragedy. In these respects, it lies beyond of the economists’ expertise. Nevertheless, governments’, businesses’ and households’ reactions to the crisis across the globe have far-reaching economic implications. The necessary precautionary policy reactions to the corona crisis, including quarantine-measures and lockdown-decisions, have a tremendous, and potentially even larger, short-term impact on economic activity than the virus itself. However, one also notices an increasing number of government initiatives to mitigate the economic impact on people and businesses. Making accurate economic forecast in this kind of environment is exceptionally difficult. All, economic projections are complicated by substantial uncertainty since it’s unclear when the virus outbreak will be contained and what policy reactions may yet be seen.

Nevertheless, it’s clear that the economic shock will be severe and shared across the globe, though the magnitude may differ between countries. The rapid spread of the corona-virus, first within China, then from China to the rest of the world, and currently across Europe in particular, took most people by surprise. In February we acknowledged the significant impact on the Chinese economy, but now it’s clear that the corona crisis has become a global problem. Therefore, the impact on our global economic scenario is very significant. It is clear that at the moment Europe is in the frontline of the corona pandemic, but we’re convinced that all continents will be affected in the near future. In particular, as we write, the situation in the US is deteriorating rapidly.

Generally speaking, we believe that the corona crisis will cause a deep, but temporary economic shock and that a recovery will follow in the second half of this year and in the course of 2021 (also see KBC Economic Opinion of 16/03/2020). That the shock is temporary in nature is suggested by a number of insights. First, economic fundamentals are still strong. This is currently the case as reflected in low unemployment rates and strong investment appetite. Second, the monetary and fiscal stimulus will mainly support the recovery, perhaps rather than weakening the crisis itself. Finally, the number of corona cases in China is stabilizing, indicating that it is possible to get the virus under control. Moreover, we see the first signs of a gradual economic recovery in China.

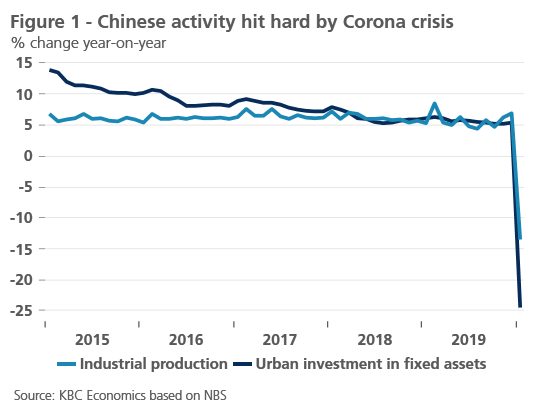

Focusing on the latter argument, last month’s scenario for the Chinese economy, the first economy to be hit by the corona crisis, is broadly being confirmed. There are significant signs that the virus spread may be starting to coming under control and we see that economic activity is gradually recovering after the massive measures that were taken earlier this year to contain the virus outbreak. Both sentiment as well as activity have been hit hard (figure 1), but Chinese companies are gradually restarting their production again. For example data on coal consumption and road congestion are gradually signalling a resumption of business. The substantial policy stimulus measures will help underpin this recovery as well. However, since supply chains remain distorted and the global economy (mainly EU and US) will be affected severely by the corona crisis, we have further downwardly adjusted our Chinese growth forecasts. We now expect growth in the first half of 2020 to be even lower than we first envisaged. This results in a 2020 real GDP growth of 3.5%. Thereafter, we project annual average growth to recover in 2021 and reach 5.7%. Hence, in the longer-term China avoids a hard landing, but this year will be characterised by a substantial if temporary decline in growth as a consequence of the economic shock caused by the corona crisis.

Though economic data at the start of this year were showing clear signs that the euro area economy was recovering from the softness of 2019, the corona virus now represents a major negative influence on activity. The virus seems to be continuing to spread within euro area economies at a rapid pace which has triggered major policy reactions going as far as national lockdowns. The corona crisis is now expected to lead to a temporary contraction in the euro area economy. For the euro area as a whole, we project annual average real GDP growth to become substantially negative (-0.7%) in 2020 (figure 2). Business cycle developments will be synchronized across Europe, but the magnitude of the impact on different euro area economies will differ. This will depend on several factors such as the quality and capacity of national health care sectors, countries’ capacities to implement fiscal stimulus measures, country-specific economic vulnerabilities, the importance of the tourism sector for the economy and interconnectedness in EU and global supply chains. The euro area recovery is expected to start in the second half of 2020, bringing the euro area back to its long-term (moderate) growth path in 2021 (+1.1%). In these forecasts we incorporate the impact of a substantial monetary and fiscal stimulus. In the absence of these policy reactions, or in the event that the virus were to spread further and faster, and the policy measures to contain it were to become even more draconian, it is likely that our scenario would prove to be too optimistic. Hence risks are clearly tilted to the downside.

The US economy is also expected to be heavily impacted by the coronavirus. We believe many underestimate the corona crisis impact on the largest economy of the world. We have downwardly revised our annual real GDP growth forecasts for 2020 from 1.7% to 0.5%, reflecting widespread negative impacts from the pandemic. US-specific issues in public health infrastructure and the labour market mean the corona virus is likely to spread fast. Data from the Bureau of Labour Statistics (BLS) show that only 28.8% of workers can work from home, mostly people active in management, business and financial operations. Detecting and deterring the virus spread in the US may also be hampered by mixed messaging from the Trump administration about the seriousness of the virus and whether or not it is safe to go to work. Moreover, in the US there is no national paid sick leave. For those who do have paid sick leave, it is not substantial. The general aversion to seeking medical care in the US due to high costs means many workers will continue to work even if they are sick, likely increasing transmission. And while US insurers have waived cost of testing, there still remains a shortage of testing kits and too restrictive criteria to qualify for testing. This means that the number of reported cases in the US likely massively underestimates the number of actual cases. Also hospital capacity is likely to be inadequate. Despite these downside risks, in line with other regions, in the US an economic recovery is expected after the temporary drop with 1.4% real GDP growth in 2021.

Box 1 - Corporate debt

Growing risks in the corporate debt market have been on the radar for some time. Since 2008, global credit to non-financial corporations has grown in both absolute terms and as a percent of GDP (from 78% to 93% according to the BIS). What’s more, several indicators suggest that, at least for some countries, the vulnerabilities in corporate debt markets have risen. Given the rapidly changing economic environment due to the spread of the coronavirus, these vulnerabilities are now being put under a spotlight.

US corporate debt stands out in particular. Since its last peak in 2008, at 72% of GDP, corporate debt in the US is only marginally higher today, at 75% of GDP (figure B1.1). However, the quality of that debt has clearly deteriorated, with a significantly higher portion of that debt rated BBB, the lowest rating in the investment grade grouping. This presents a risk in a possible scenario where a wave of ratings downgrades could potentially lead to a huge shift in corporate debt markets, with formerly investment grade debt flooding the high yield market (debt with a rating below BBB). Since some investors are required to hold investment grade debt, such a risk scenario could force creditors to dump their newly lower-rated debt, which would further weaken the corporate debt market.

But it’s not only the investment grade portion of US debt that has gotten riskier. According to a December 2019 publication by the Financial Stability Board, vulnerabilities have risen in the leveraged loan market. These vulnerabilities include higher debt levels of borrowers, weaker creditor protections and a shift in creditor composition from mostly banks to more non-bank investors. Indeed, the debt at risk for SMEs in the US is quite large and has risen since 2009. This coincides with very weak corporate profitability for US SMEs (figure B1.2).

Hence, the risks are that the rapidly deteriorating economic outlook will worsen corporate profitability, make it more difficult for highly indebted companies to service their debts and could lead to increased ratings downgrades. Tighter financial conditions could also make it more difficult for some corporates to roll over their maturing debt. As such, the recent significant action taken by the Fed is important in terms of keeping markets running smoothly. Fiscal stimulus that supports corporations and small businesses during this period will also be important. Such support will help businesses ride out the disruptions caused by the coronavirus spread and avoid excessive disruptions in corporate debt markets.

Oil shock shaking markets as well

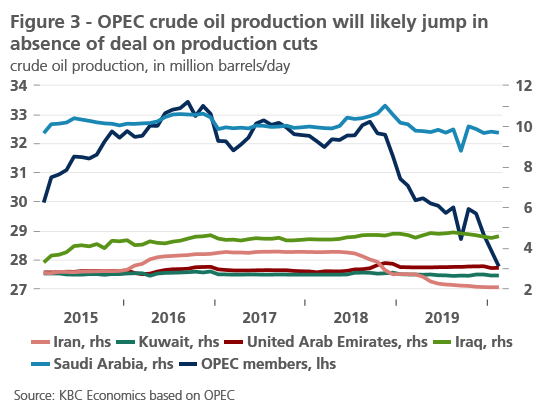

On top of the concerns and uncertainty about the corona outbreak, financial markets were shaken by developments on the oil market in recent weeks. The inability of the OPEC+ members to come to a new agreement on production cuts a few weeks ago meant a structural change in the oil market. The OPEC+ strategy of market price stability was replaced by a strategy of pursuing market share via price competition through production increases (figure 3). After the negative oil demand shock from the impact of the coronavirus in previous weeks, this decision led to a positive oil supply shock. The combination of the negative demand shock and the positive supply shock put considerable downward pressure on oil prices, by leading to a sizeable oil supply glut. In line with the macroeconomic scenario, the oil price bottom is now expected to reach 30 USD per Barrel Brent in Q2 2020. From Q3 on, oil prices will only gradually increase (40 dollar at the end 2020) and reach 50 dollar once the oil market has rebalanced (i.e. supply glut removed) by the end of 2021. This market rebalancing will be driven on the supply side by production cuts by US shale oil producers and on the demand side by increasing oil demand due to a recovering world economy.

The lower oil price scenario together with the expected global growth slowdown due to the Corona crisis, has significant implications for our inflation projections. Both for the euro area and for the US, we have revised down our inflation forecasts for 2020. Both core – due to the demand effect – and headline inflation – resulting from the oil price effect – will be lower than initially projected. For Europe, however, the lower oil price will likely partially the economic damage caused by the corona crisis since household’s purchasing power will be boosted by the lower oil price and particular oil-intensive industries can benefit from lower production costs.

Central banks ready to act

To provide extra stimulus for economic activity and to prevent large spillovers to the broader financial system, major central banks have already acted. The European Central Bank (ECB) initially disappointed markets somewhat by only announcing easier and cheaper access to long-term financing for banks and an additional envelope of €120bn temporarily added to the Asset Purchase Programmes (APP). Markets had come to expect a large and wide-ranging policy package from the ECB. The decision to not cut the policy rate – although at -0.50% it is already significantly below zero – was interpreted by markets as signalling the ECB may have reached its effective Lower Bound on interest rates and, more generally, sparked worries that the scope for further monetary policy support in the euro area is very limited if not exhausted. More recently, the ECB launched a new temporary asset purchasing programme to further tackle the risks to the economic outlook. The so-called Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) will consist of asset purchases worth EUR 750 billion that will be carried out until the end of 2020. We don’t expect any further policy rate cuts by the ECB given current low interest rate levels as well as the already substantial negative side-effects of these negative interest rates. However, further unconventional measures may be required in circumstances where the unprecedented nature of the crisis means no possible form of policy action can be definitively ruled out.

The Federal Reserve has implemented a fast, substantial and wide-ranging policy response. After a surprise interest rate cut by 50 bps at the beginning of March, a second round of even more drastic stimulus measures was announced less than two weeks later. A wide ranging series of liquidity measures to support the functioning of financial markets has also been introduced. Although there has been no hard economic data pointing to a material deterioration in US economic conditions, the Fed cut policy rates by a full percentage point to the effective floor (0%-0.25%) and indicated it will keep interest rates close to zero until the economic barometer reverses. The US central bank fears that the economic blow of (tackling) the coronavirus will be particularly severe. In the past, similar measures have only been taken in crisis mode. As if the large interest rate cut wasn't enough, Chairman Powell announced new asset purchase programs and a number of new liquidity support measures. The Fed will expand its portfolio of government bonds by USD 500 billion and its mortgage-backed securities by USD 200 billion. It also announced large commercial paper and primary dealer facilities as well as enhancing FX liquidity through swap lines with other major central banks. Through these multiple channels, it intends to provide ample liquidity to ensure the proper functioning of the market. A few days earlier, the Fed also decided to dispose of more than USD 5000 billion this month through repo operations for domestic counterparties. We don’t think the Fed will cut the interest rate further into negative territory but additional unconventional actions may be forthcoming.

The stimulus measures by the US, euro area and other central banks weren’t enough to stop the massive risk-off flows in financial markets though. Equity markets have plummeted, government bond yields initially slumped and then partly retraced those drops while assets conceived as a safe haven have become much more attractive. In the short term, we expect long-term government bond yields to stay relatively low. A very gradual upward trend is likely to accompany a recovery in economic growth. Intra-EMU bond spreads against the German bond yield are projected to widen further in the short term given the risk-off environment and increased concerns about the weaker euro area countries. In particular Italy, which until now is hit hardest in the euro area by the corona epidemic, will see its spread increase significantly in the coming weeks. A very muted spread narrowing will likely only happen in the course of next year. While the near term outlook is choppy, our scenario of longer-term euro appreciation against the USD still holds, driven by weakness in the US economy and extremely accommodating Fed policy.

Box 2 - European housing market slows down, but does not correct

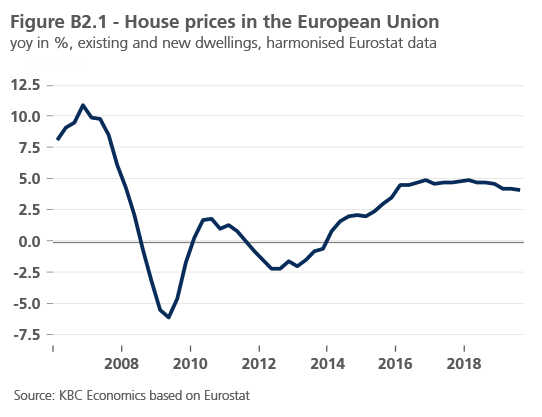

Europe’s housing market has been in very good shape in recent years, mainly thanks to low interest rates and strong job creation. According to the latest Eurostat figures, the annual increase in house prices in Q3 2019 was more than 5% in 15 of the (then) 28 EU Member States. EU-wide, prices in Q3 were up 4.1% compared to a year earlier. Although still robust, the dynamics of price increases have weakened over the past quarters (figure B2.1). This suggests that the European housing market is over its peak. Certainly in the context of the severe corona crisis, this raises the question of how much the slowdown in price dynamics will continue and whether it will finally result in a price correction.

Housing supply is becoming less rigid

In addition to strong demand for real estate, the rise in prices in the European housing market was also due to the slow adaptation of supply to demand. Supply-side constraints are due, among other things, to long permit procedures, strict land-use planning or a lack of construction workers. They are reflected in the European Commission's monthly survey of construction companies (figure B2.2). One in three sees supply factors as the biggest barrier to their activity. Although still strongly present, supply constraints, however, seem to have decreased somewhat. Since the beginning of 2019, the indicator has fallen back mainly in countries where it has risen the most in recent years, in particular in Central and Eastern Europe. This development explains why the dynamics of house prices in the EU have slackened somewhat in recent quarters.

The coronavirus outbreak will severely affect GDP growth and, subsequently, household income growth in the EU in 2020. Together with less rigid housing supply, this will further, and more substantially, slow down house price dynamics. From an economic perspective, a major price correction is unlikely as several factors compensate for these negative influences. In particular, continued low interest rates and increased risk aversion in financial markets due to the corona crisis will support investor demand for real estate and thus prices. We expect house prices in the EU to rise further by some 2.5-3.0% in 2020, compared to an estimated 4.7% in 2019.

More structurally, demographic changes might also support house prices. One headwind in recent years has been the falling number of EU citizens aged 20-49, which slowed the pace at which new households were created. But Eurostat forecasts that the decline of people aged 20-49 might ease over the coming years. This will support household formation and demand for housing, and hence price dynamics over the medium term.

This aggregate outlook for the EU as a whole hides differences at the country level, however. The degree of overvaluation of the housing market and the size of household mortgage debt are two risk factors that determine whether the expected slowing down of house price dynamics can still result in a price correction in particular countries. The housing markets in Luxembourg, Sweden, Austria and Italy are, in our view, the most vulnerable to a correction. Moreover, it is obvious that the corona crisis will temporarily reduce the number of real estate transactions which may cause increased volatility in the market.

All historical quotes/prices, statistics and charts are up-to-date, up to and including 16 March 2020, unless stated otherwise. The positions and forecasts provided are those of 16 March 2020.