ECB should include asset prices in its inflation measure

ECB should include asset prices in its inflation measure

On 23 January, the ECB launched a review of its monetary policy strategy, which is expected to be completed by the end of 2020. Not only the inflation target rate, but also how to measure price stability and inflation as a concept should be high on the agenda. The ECB should quantify inflation as it occurs in economic reality, including a broad range of asset prices. Conceptually, this is well-supported by economic theory. Empirically, this may be challenging, but, as Fed research shows, not impossible to do. Omitting asset prices is dangerous. It may lead to the incorrect diagnosis that inflation, as officially measured, is consistently too low, and that consequently even more and longer policy stimulus is needed. In fact, the opposite conclusion might be reached based on an inflation measure that adequately captures economic reality.

On 23 January, the ECB announced the start of a review of its monetary policy strategy, which is expected to be concluded by the end of 2020. The review takes the ECB’s primary statutory mandate to deliver price stability in the euro area as a given.

There has been an active debate about the monetary policy strategy that the ECB uses to deliver on this mandate. Possible alternatives to the current numerical inflation target, for example, have been discussed, as well as the ECB’s forward guidance and the scope for future quantitative easing in the ECB’s toolbox. There has been, however, relatively little debate about the most fundamental ingredient of the ECB’s strategy, which is the statistical definition of inflation. Currently, the ECB defines price stability in terms of the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) for the euro area. However, as former Bank of England policy maker Goodhart pointed out, the appropriate definition of inflation is the loss of value of money, and not the rise of a particular consumer price index.

Close attention to this issue is warranted during the strategy review. No monetary policy strategy, however perfect, can deliver on the mandate if the ECB gets the targeted concept itself wrong. In separate speeches, current and former ECB governors Mersch and Coeuré drew attention to the apparent gap between the public perception and the official measures

of inflation in the euro area. According to a survey by the European Commission, households believed that annual euro area inflation between 2004 and 2018 was close to 9%, when officially it was 1.6% based on the HICP. What if these survey data paint a largely accurate picture and official HICP inflation does not fully capture economic reality anymore ?

This suggests that the ECB is ‘missing something’ in its current quantification of the inflation concept. If that hypothesis is correct, this shortcoming would have a serious consequence. In January 2020, HICP inflation was 1.4% (i.e. clearly not ‘close to 2%’). This may lead the ECB to wrongly believe that the current policy accommodation remains needed (or must even be scaled-up) to lift official inflation, while actual inflation may already have reached its desired level or even overshot it. In that case, monetary policy tightening would be required rather than stimulation.

Moreover, the same survey responses imply that monetary policy effectively has an impact on inflation. It just does not appear in the HICP measure of inflation. This is an important insight to counter a recent ECB Working Paper1 that suggested that the ECB’s monetary policy has become more and more ineffective in the past decade to prevent inflation from deviating persistently from the ECB’s inflation objective.

Inflation is not ‘missing’

How do we explain the paradox of a sustained period of extremely accommodative monetary policy in the euro area coinciding with an official inflation rate that stubbornly remains well below the policy target ?

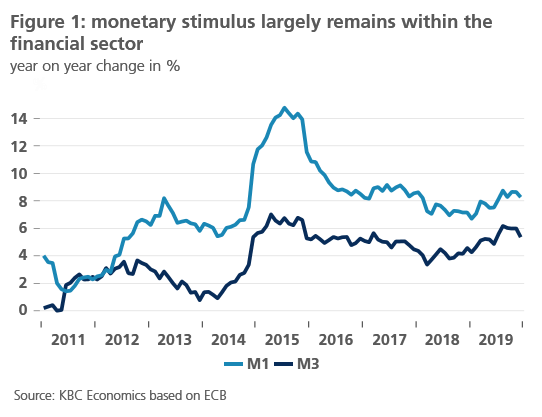

Part of the answer is that accommodative monetary policy has led to substantial growth in the narrow measure of the money supply (M1), which is relatively closely related to monetary policy and the financial sector. Growth of the broader measure of money supply (M3) was much more moderate (Figure 1). It is the broad money supply that is used to purchase goods and services and thus affects official HICP inflation.

In other words, the monetary expansion by the ECB has had a substantial impact on the financial sector. Consequently, inflation has not shown up so much in goods and services prices, but rather in (financial) asset prices. Just as HICP headline inflation may at any particular point in time be driven by different HICP components (services, goods, energy, food,....), actual inflation at this moment appears to be driven rather by the inflation component ‘asset prices’ than by the components in the current HICP index.

Incorporating asset prices

A first step to take this into account is the restarting debate in the euro area about how, if at all, to include imputed costs of Owner Occupied Housing (OOH) in the measure of inflation. In contrast with the CPI measure in the US, the current HICP basket only includes actual rents paid. As a result, it omits to a large extent house price inflation, which is closely related to the interest rate environment and hence to monetary policy. According to a recent Eurostat estimate, housing costs represent about 24% of Europeans’ consumption, and including OOH in the price measure would at this moment increase measured inflation by as much as 0.3 percentage points in the euro area.

The case to include asset prices in an adequate measure of inflation is not restricted to house prices. The conceptual need to include a broad set of financial assets, including equity prices, has been well-established in the theoretical literature for quite some time by e.g. Alchian, Klein and Goodhart. The weights of financial assets in such a measure may vary among economies depending on their macroeconomic importance. The difficulty lies in the empirical construction. However, the ‘full dataset’ variant of the New York Fed’s Underlying Inflation Gauge (UIG) index shows that it is statistically feasible to include financial variables in a meaningful way. The UIG index includes, among other variables, government and corporate bonds, real estate, stocks and commodities. Unsurprisingly, since January 2014, UIG inflation has on average been 75 basis points higher than the official CPI inflation in the US.

The case for ECB policy normalisation

This suggests that the current ECB policy is raising inflation, but not in the components that are measured in the official HICP. Instead, inflation is mainly appearing in the form of asset price inflation. The short term policy implication is clear: doing more of the same will deliver more of the same. Hence, there is a strong case to start normalising monetary policy, with the additional benefit of mitigating some of the negative economic side-effects of the current monetary policy stance. Asset prices should therefore not be fully ignored when measuring inflation and setting monetary policy.