ECB cannot solve EMU debt problems on its own

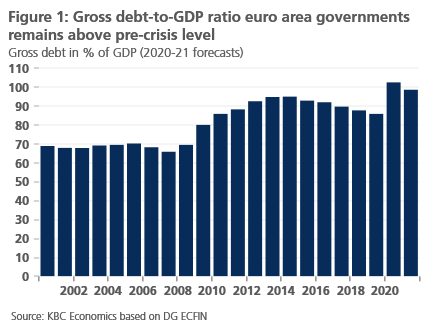

Between 2007 and 2014, the ratio of gross public debt to GDP in the euro area increased by almost 30 percentage points. In the following years it fell, but it did not come close again to the pre-crisis level. In other words, the fundamental debt problem is still present. This clearly emerges now that the Covid-19 pandemic has struck. The main responsibility for the sustainability of public finances has long rested on the shoulders of the ECB. The central bank is increasingly becoming the prisoner of its implicit fiscal responsibility. It thus loses its independence to conduct an appropriate monetary policy according to its mandate. Sooner or later, this will threaten the stability of the euro.

In the aftermath of the Great Recession twelve years ago, global public debt rose sharply. This was also the case in the eurozone (Figure 1). For the euro area as a whole, the debt ratio rose steadily from 65.9% of GDP in 2007 to a peak of 95.1% in 2014. Beneath this aggregate figure, the debt dynamics in individual members states were often quite diverse. At the height of the second wave of the crisis at the end of 2011, financial markets considered euro-area public debt unsustainable and risk premia for vulnerable EMU countries increased to such an extent that even the continued existence of the currency union was called into question. Ultimately, European institutional steps towards a banking union and monetary interventions (the OMTs or “whatever it takes”) once again brought calm to financial markets in 2012. Given the theoretically infinite firepower of the ECB, financial markets no longer fundamentally questioned the sustainability of public debt.

Debt problems never disappeared

However, the return of calm to financial markets and a moderate decline in the debt ratio from 2015 onwards did not mean that the high debt ratios had disappeared. The need for budgetary space following the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic is a painful reminder of this.

There are a number of ways to bring debt levels that are perceived as unsustainably high under control. A first way is (partial) debt forigiveness or even default by the government concerned. In the euro area, this option was only applied in 2012 in the case of Greece. Such a default would have significant negative consequences for the other Member States of the currency union and for the stability of the financial system. Therefore, in the specific case of the EMU, this solution is not workable in practice. Even in the case of the small Greek economy, the implementation turned out to be very difficult and chaotic.

A second way is to reduce the debt ratio by increasing the denominator of the ratio. Other things being equal, the debt ratio will be lower if real economic growth exceeds the real interest rate that the government has to pay on its outstanding debt. To a certain extent, that mechanism played a role in the period after 2015, causing the debt ratio to fall moderately. Moreover, the favourable growth climate was accompanied by interest rates that were kept artificially low by ECB policy, leading to lower interest charges in fiscal budgets. Nevertheless, this was not enough to bring the debt ratio back down to the pre-crisis level of 2007. The reason for this was that a third lever for debt control, i.e. an improvement in the primary budget balance, was insufficiently used despite the favourable economic growth climate.

A fourth way of controlling the debt ratio is to create higher inflation over a sufficiently long period of time. In this way, the real public debt falls as long as the nominal interest rate on the outstanding debt does not neutralise that effect through a higher inflation premium. In the eurozone, however, this path was never a viable option. On the contrary, inflation in the eurozone remained well below the ECB’s inflation target over the past decade, which even exacerbated the debt problem in vulnerable euro area countries.

ECB under fiscal domination?

All the policy options listed require some form of political choice and vision. However, European authorities tacitly chose the easy solution. Their policy inertia posed existential risks to the stability of the euro area, making the ECB feel obliged to intervene. Partly for this unspoken reason, the ECB launched its government bond purchase programme (PSPP) in March 2015, which is still ongoing except for a short pause in 2019. Moreover, following the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, the ECB increased the pace and volume of its sovereign bond purchases through the its Emergency Purchasing Programme (PEPP).

That assistance by the ECB is not negligible. At the end of 2019, the ECB had EMU government bonds worth EUR 1965 billion (16.5% of euro area GDP) on its balance sheet. This is almost one fifth of the total gross debt of EMU governments.

The stabilising mechanism of such purchase programmes sounds easy and therefore tempting. Bonds bought by the ECB from EMU sovereigns are economically irrelevant as long as they are on the ECB balance sheet. After all, the central bank itself is part of the government, which then owns government debt securities (i.e. of itself). In fact, the ECB simply replaces one government debt security (bonds) with another (‘base money’). The bonds bought by the ECB only regain their economic relevance when the ECB sells them on the market again or requests that bonds are redeemed at maturity. However, until further notice, bonds are reinvested at maturity. And this will undoubtedly continue to be the case for some time to come.

In addition to the effect of this temporary debt neutralisation, ECB purchases de facto eliminate interest payments due on the bonds in question. After all, these interest payments increase the ECB’s profits. Eventually, these will flow back to the ECB shareholders via the paid-out dividend. And these are the national governments through their own national banks. That completes the circle. Intuitively, the ‘disappearance’ of interest charges is the result of the central bank replacing an interest-bearing debt instrument (bond) with an interest-free (‘base money’). In extremis, this ‘base money’ thus plays the role of a perpetual zero coupon government bond.

It all seems simple, but the great danger is that the ECB will increasingly become the prisoner of the fiscal responsibility imposed on it. In this way, it loses its independence to conduct an appropriate monetary policy (‘fiscal dominance’). Can the ECB, if it deems it necessary on the basis of its own policy mandate, tighten its asset purchasing and interest rate policy without having to consider the consequences for public finances? If not, the stability of the euro will sooner or later be in danger.