Dutch economic growth: not quite as impressive as it might seem

Since 2014, the Dutch economy has been one of the fastest growing larger eurozone economies, while the Belgian economy has struggled to keep pace with the eurozone average during that period. However, this growth bonanza in the Netherlands is largely an illusion, as it mainly reflects a catch-up from particularly severe losses during the 2008-2013 crisis period. Taking a longer view stretching back to the turn of the century, both economies have grown at approximately the same rate. Moreover, the Netherlands is very vulnerable to the current international slowdown in growth, while the extremely low interest rates due to their pressure on the pension system increase its vulnerability even further. Unlike most other euro area countries, the Netherlands fortunately has budgetary room to absorb a growth slowdown. But there is no question of abundance here either. This is not a problem for the Netherlands, but it illustrates how limited the scope is for activating fiscal policy in the eurozone through greater policy coordination.

Growth champion, or not?

“Milk and honey, abundance”, is how the Dutch singer-songwriter Boudewijn de Groot sings about the Low Countries. Macro-economic reports about the Netherlands now spontaneously conjure up that image. At 2% (on an annual basis, compared to the previous quarter), real GDP growth in the second quarter of 2019 was more than twice as high as the average for the eurozone. Of the larger euro area countries, the Netherlands has had the strongest economic growth since 2014, after Spain. Despite an expected growth slowdown, this is expected to remain the case for some time to come.

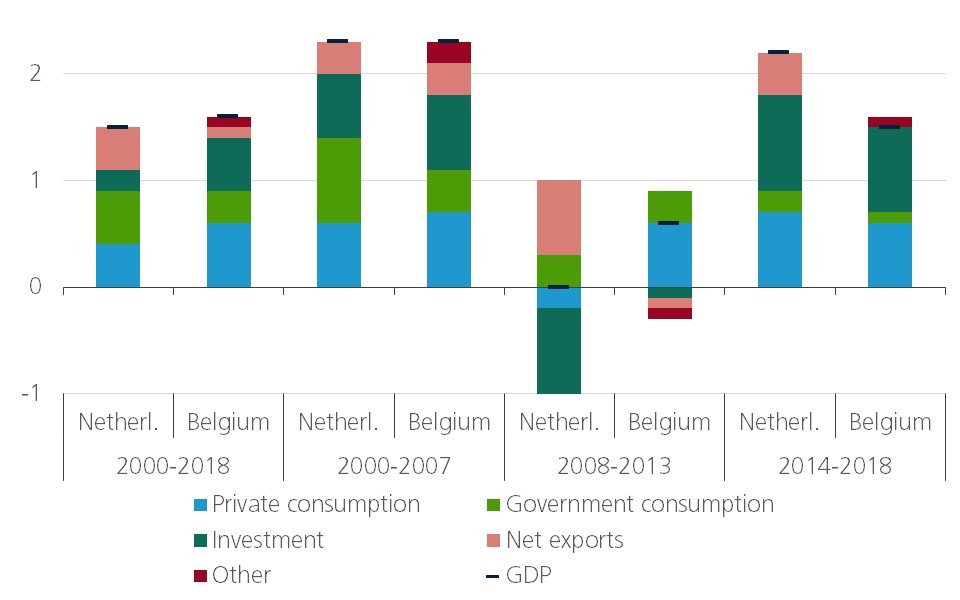

This growth performance seems to contrast sharply with that of the Belgian economy. In recent years, the Belgian economy has seldom, if ever, reached the average growth level of the eurozone. But appearances can be deceptive. After all, in a somewhat broader time perspective, Dutch growth looks much less spectacular. Since the turn of the century, the Belgian economy has even grown slightly more than the Dutch economy (figure 1).

Figure 1 - Growth composition (average annual year-on-year change of real GDP in percentage and growth contribution of demand components in percentage points)

In the pre-crisis years, both economies grew at exactly the same rate. The strong growth of the Dutch economy in recent years is mainly the result of the recovery from the severe blows during the crisis years 2008-2013. While the Belgian economy grew by an average of 0.6% a year during this period, the Dutch economy was, on balance, stagnating. In addition to the international recession, the Dutch economy was also faced with a real estate crisis and the pension system came under pressure because of the low interest rate (see below). This resulted in a sharp contraction in investment, while households also cut back on their consumption. The recovery of both demand components has made up most of this lost ground in recent years. This was further reinforced by the fact that Dutch exports, were reaping the benefits of the international economic boom to a greater extent than their Belgian counterparts.

Vulnerable

The Netherlands scores better than Belgium on many other macroeconomic parameters (See: KBC Economic Opinion of 15 October 2018). Nevertheless, the Dutch economy is very vulnerable to the current international slowdown. The recession in industry is already striking relatively hard. In contrast to Belgium, the Netherlands belongs to the group of medium-sized and large industrial countries where production in the manufacturing sector has been declining since the end of 2018. There is a risk of even greater difficulties if Brexit were to end badly or if the trade war were to escalate. As an open economy, the Netherlands is very vulnerable to this, as is Belgium.

Through their impact on the pension system, low interest rates are also a specific threat. The Dutch pension system relies to a very large extent on a second pillar, in which pension reserves are built up by saving. In general, it is considered to be a very solid system, but the current environment of extremely low interest rate puts it under pressure. It affects the yield from the invested savings and increases the present value of the future pension liabilities. This imbalance encourages pension funds to limit benefits or increase contributions. This, of course, affects the confidence and purchasing power of Dutch consumers. The system has already come under pressure in the aftermath of the financial crisis, resulting in a drop in domestic demand (see above). The recent new lows in interest rates and the further easing of ECB policy are now threatening to repeat that history. The public criticism by the Governor of the Dutch Central Bank on the ECB’s latest policy decisions should probably be understood in this context as well.

Generous budget

On the other hand, the Netherlands received a compliment from ECB President Draghi on the basis that, with plans for an investment fund, it seems to be responding to his call for a more flexible fiscal policy. Since 2016, the Netherlands has been accumulating government budget surpluses, which means that the government debt is expected to fall below 50% of GDP this year. The country can therefore afford to ease its fiscal policy somewhat, as one of the few euro zone countries, along with Germany, by the way.

On Prinsjesdag, the government proposed a budget with extra spending on health care, education, police and defence. The recent Pension Agreement will also result in more expenditure, while the new climate policy will include both extra expenditure and new charges. Families can count on a reduction in charges. The Dutch Central Planning Bureau estimates that the budget surplus will fall from 1.5% of GDP in 2018 to 0.3% of GDP in 2020. The structural budget surplus of 0.7% of GDP in 2018 would fall to a deficit of 0.4% in 2020. This means that it remains just within the medium-term objective (MTO) of the European budgetary framework.

Underutilization

The deterioration of the structural budget balance by more than 1% of GDP suggests a significant growth impulse from fiscal policy. Here too, however, the ‘abundance’ may be smaller than it appears. Due to capacity constraints and tightness in the labour market, the Dutch government is unable to fully spend the planned budgets, e.g. for infrastructure works. The so-called underutilisation amounted to 1.4% of budget expenditure in 2018, compared to an average of 0.5% in 2010-2017 (source: Central Planning Bureau). For 2019 and 2020, the Central Planning Bureau also takes into account underutilisation.

Fiscal policy will therefore only be able to make full use of the available budgetary room for manoeuvre as the slowdown in economic growth frees up production capacity. From a Dutch perspective, this is not a problem, even a healthy situation. From a European perspective, however, it illustrates how limited the possibilities are for activating the fiscal policy in the euro area through greater coordination of national policy. Countries in need of a more flexible policy usually have no room for it. Countries with budgetary room for manoeuvre often have a less urgent need for it and run up against capacity limits in order to use the financial room for manoeuvre.