Could there be some method behind Brexit Madness? Long Read

Our longstanding view has been that the Brexit process would be softish but not smooth. While there are still concerns about it being the former, negotiations have been anything but smooth. This note looks at a framework that might explain why, in spite of the chaos of recent weeks, the mood in financial markets still seems reasonably relaxed that a ‘hard Brexit’ can be avoided.

Read the publication below or click here to open the PDF

Introduction

The agreement at this week’s EU summit to remove the threat of the UK crashing out of the EU on March 29th and replace it with three distinct possible paths, one of which will have to be definitively chosen no later than April 12th , represents a determined effort to draw a line under what has been a protracted and frequently painful negotiation.

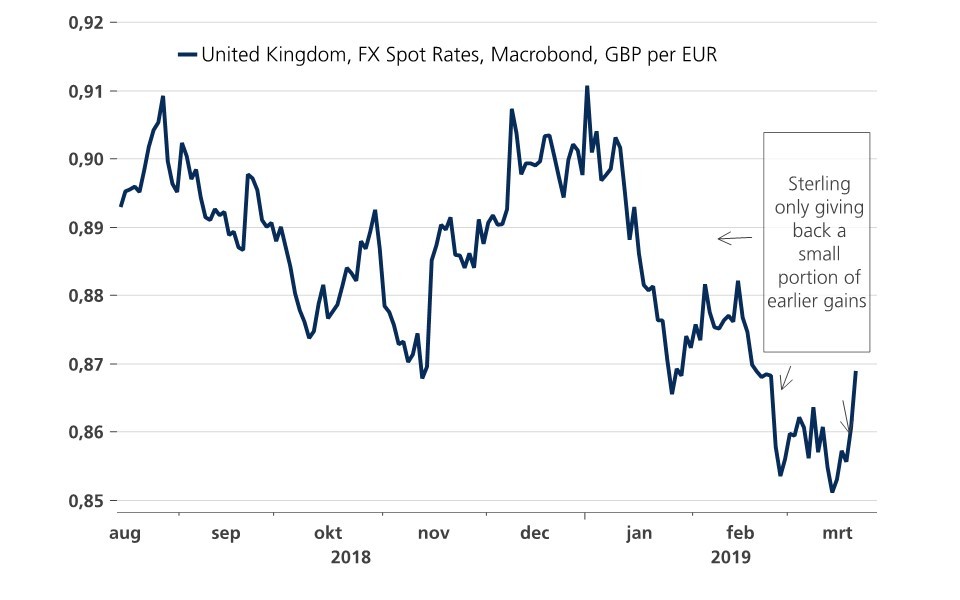

Although there has been a little more volatility in GBP exchange rates of late, the message from the markets, as indicated by figure 1 below, is that traders and investors still see a ’no deal’ exit of the UK from the EU as very unlikely. As a result, the improvement in Sterling evident since the turn of the year saw only a marginal correction through the past couple of trading sessions. Do the markets know something that appears to have escaped politicians and the media or are we facing into major event risk that could entail a sharp correction in markets through the next month or so?

Figure 1 - Sterling not suggesting 'no deal' outcome now likely GBP/EUR

While negotiations on the UK’s exit from the EU have generated a great deal of heat at the political level, thus far there seems to be little light in regard to what the UK hopes to achieve from what has often seemed to be inconsistent and sometimes impossible demands that it has made of the EU. Does this simply reflect confusion and chaos in political circles that is partly the product of a nation long divided in its attitude to Europe? If that is the case, one might expect a clearer risk premium to be built into UK assets than is currently the case and this would also imply substantial volatility would have occurred in response to rapidly changing political developments of late.

Could it all be a Game?

One admittedly contentious possibility might be that markets think that there could be a method hidden deep beneath the madness. On this view, really damaging outcomes will be avoided because UK politicians are engaged in a clever if confusing strategy to maximise the concessions they might win from what is clearly a very weak bargaining position. Seen through a ‘Game theory’ lens, the various twists and turns could be elements in a complicated plan entailing a sequence of interactions with other ‘players’ designed to win the best possible deal for the UK. A less structured but still feasible approach would be a game of ‘bluff’ in which efforts at confusion are the only elements of strategy!

Game theory provides a formal means of analysing interactions between individuals (or groups) and how these affect their decision making and push outcomes in particular directions. Game theory is used to analyse developments in fields ranging from politics to mathematics as well as economics and most other social sciences.

The starting assumption in standard Game theory is that all ‘players’ act rationally. However, in current circumstances, rational behaviour for UK negotiators could be to act unpredictably and seemingly irrationally in order to increase uncertainty among other ‘players’ and thereby reduce any power advantage they might have. Behavioural Game theory and a number of related fields look at a range of approaches of this fashion. On this interpretation, it might be argued that the UK is playing the negotiations really well!

In terms of the Brexit process, it is also important to understand the nature of the ‘game’ for both sides. Importantly, the ‘payoff’ should be seen in political as well as economic terms. If Brexit was viewed exclusively in economic terms, the UK would not have voted to leave the EU in the first instance and, having done so, it would now be completely at the mercy of EU negotiators.

So, the Brexit ‘game’ can’t be analysed in terms of damaging GDP impacts alone. This is important because the greater uncertainty that attaches to estimating political gains and losses relative to their economic counterparts makes it harder to definitively say how much leverage the EU might have vis-à-vis the UK in terms of the threat of no deal’. In this context, a YouGov poll on March 14th found 43% of Britons favoured leaving at end-March compared to 38% that favoured a delay. So, political drivers may reduce the perceived economic costs of a no deal Brexit within the UK. Such ‘rational irrationality’ may make negotiating the endgame a little easier for Mrs May.

One consideration that might be consistent with financial markets seeming complacency at present is that in terms of the Brexit ‘game’, the withdrawal agreement should be seen as the end of the beginning rather than the beginning of the end. For the UK, progressively more important ‘rounds’ lie ahead in the shape of a deal on the future trading relationship with the EU (provided that a withdrawal agreement can be reached) and beyond that in the shape of a broader range of trade deals with other countries. While the twists and turns of the past couple of years will not encourage the view that dealing with the UK might be easy, if a withdrawal agreement with the EU materialises, there will be a sense that it can both (eventually) deliver on its promises and strike a hard bargain.

A key consideration is that the UK government is fighting on two fronts

Of course, for Theresa May’s government, dealing with the EU has been far less complicated than winning domestic support for any deal. A 1988 paper by Robert Putnam (Diplomacy and Domestic Politics, the Logic of Two Level Games) introduced the idea of ‘two level games’ in which a government involved in international negotiations might face particular difficulties because of a need to work to ensure domestic ratification simultaneously with the completion of international agreements.

One possibility suggested by Putnam was that domestic differences might encourage greater co-operation from international parties (to enhance the prospect of a mutually successful outcome- which in the case of Brexit might be seen as avoiding an economically damaging no deal outcome). Judged from this perspective, in circumstances where there were notable differences within both UK politics and the broader population, it could be argued that there was a strong incentive for Theresa May to sustain some element of domestic tension to win some concessions from the EU. However, a persistent problem has been to ensure these domestic differences didn’t become so wide that they would completely undermine the credibility of the UK government with its EU counterparts.

This interpretation emphasising the benefits in sustaining an element of tension at home could rationalise (at least to a point) seeming inconsistencies in the messaging of the UK government both to domestic and EU audiences. However, Mrs May also needed to deliver a domestic ratification of her agreement with the EU. The major stumbling block to the withdrawal agreement is the divided nature of the UK parliament. This is reflected in an increasingly bitter split between various factions in the minority government Conservative party that is mirrored to varying degrees across most other political parties and reflects the divisive 52%-48% Brexit referendum result in 2016. To overcome such divisions she may have been encouraged to set up a game of ‘chicken’ in which one domestic group (or both) eventually alters its position, along the lines depicted in the diagram below, to avoid catastrophic damage.

To play this domestic game successfully, Mrs May needed to run the clock down towards the Brexit deadline while keeping outcomes at both ends of the spectrum (no deal and remain) firmly open as possibilities. This she has managed successfully even if very awkwardly at times. A key task in this element of the domestic ‘game’ was to evaluate first the strength of domestic support for both a hard Brexit and remaining in the EU, then to assess the intensity of each side’s fear of their least preferred outcome and using this to attempt to move elements of one or both groupings (inside and outside the Conservative party) away from their preferred position. Progress towards such a goal would also have been very time consuming and consistent with the protracted difficulties that have marked the negotiation process to this point.

The heavy defeats Mrs May’s government suffered in January and again in Mid-March suggest her progress in moving UK Members of Parliament away from their preferred positions has been very limited. This process has been painful particularly for Mrs May but that should have been expected. A frequently cited example of Game theory, ‘the prisoner’s dilemma’, suggests circumstances in which a group might adopt an obstinate position even if other positions held out some possibility of better results to lessen the likelihood of their least preferred outcomes.

Mrs May is now desperately trying to draw various factions within the UK parliament away from such ‘non-cooperative games' towards a compromise centred on ‘her’ deal (see Table 1). In this regard, her task is to move MP’s away from their respective positions in column 1 of the diagram below by emphasising the risk they could end up in their least preferred options in column 3. In this way, she now hopes to push elements of both factions both within and outside her own party into the centre column before April 12th. The two stage structure of the timetable agreed at this week’s EU summit is quite helpful to her in this regard.

Table 1 - Stances of Brexiteers and Remainers

| Want | Might accept | Must avoid | |

| Brexiteers | No deal | Some deal | No Brexit |

| Remainers | No Brexit | Some deal | No deal |

Where next?

Rather than simply agree to the UK government’s request for a three month extension to end June, the EU summit of March 21st/22nd agreed that the initial March29th deadline for the UK to leave the EU would be extended. If the UK government wins support in the British parliament for its withdrawal agreement, an extension to May 22ND would occur. If, however, Mrs May loses this vote, the UK government would have until April 12th to ‘to indicate a way forward before this date for consideration by the European Council’. This implies that by April 12th, the UK would either agree to participate in upcoming elections to the EU parliament and, accordingly, be offered a potentially lengthy extension of a year or more or leave the EU without a deal no later than May 22nd. While some commentary suggested this outcome was a damaging defeat for Mrs May. This formula broadly corresponds to proposals mooted by UK government sources earlier in the week.

The new two stage deadline of April or May is a clever device that should increase risk aversion among at least some of the factions within the UK parliament. The outcome of a prospective third vote next week should be much closer than previous debacles but is still uncertain. The possibility, if Theresa May loses, of a lengthy extension that might allow both a general election and a second referendum as well as pose the more immediate problem of holding EU elections is a marvellous mechanism for putting pressure on UK parliament. For the main parties, the threat of a voter backlash as well as the risk of even more public and damaging internal divisions might encourage reluctant support for the current withdrawal agreement or something quite similar.

It is far from clear that there is any method in the madness surrounding Brexit. However, financial markets remain reasonably confident that a withdrawal agreement will be reached and wide reaching economic and political fallout from the UK crashing out of the EU can be avoided. This may simply reflect the view that common sense will prevail once all other approaches have been exhausted. Alternatively, it could be that some see in recent chaos a heavily concealed pattern consistent with the strategic interactions of Game theory. If that is the case, even more complicated manoeuvres lie immediately ahead and it could become even more complex thereafter as attention turns to the UK’s future relationship with the EU.