China’s investment-led growth is a double-edged sword

China’s economy appears to be on a remarkable post-Covid-19 recovery path and is likely to be the only major country that registers positive GDP growth this year. At the same time, however, the ‘two-speed’ nature of the recovery, with the demand side of the economy lagging the production side, flags recurrent risks related to the long-term sustainability of Chinese economic growth. Although we expect the demand side to eventually fully recover, the relative weakness highlights that the much-needed transition to a more consumption-focused economy has been rather slow while debt ratios have continued to climb. However, the investment-led industrial rebound in China is not all bad, especially with investments in technology leading the way. This can still support China’s transition from a ‘high-speed’ growth model to a ‘high-quality’ one. Furthermore, if China’s recent pledge to achieve climate neutrality by 2060 is followed up with concrete action to begin the transition sooner rather than later, there will be plenty of opportunities for productive investment.

On the surface, most Chinese economic indicators show a clear, V-shaped recovery. After contracting 10% qoq in Q1 2020, real GDP growth rebounded to 11.5% qoq in Q2 2020, meaning China has already returned to Q4 2019 GDP levels. This puts China on track to be one of the only major economies with positive annual growth in 2020. Meanwhile, most other major economies aren’t expected to reach Q4 2019 GDP levels until much further down the road. Digging into the details of the latest GDP data, it becomes clear that the recovery has not been even across the economy. Investment, which had a negative contribution of 1.4 percentage points to year-over-year GDP growth in Q1, had a positive 5.0 percentage point contribution in Q2. Meanwhile, consumption contributed negatively to GDP growth in both Q1 (-5.5 percentage points) and Q2 (-3.2 percentage points).

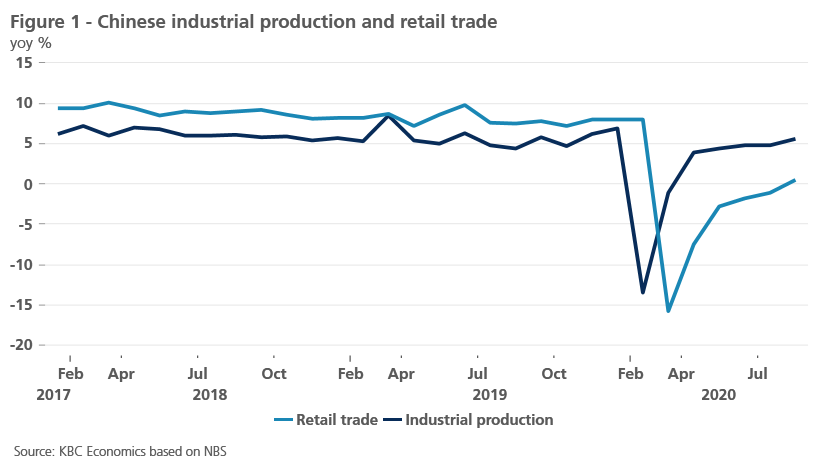

This ‘two-speed’ economy is also apparent in more recent retail trade and industrial production data. Industrial production has grown in year-over-year terms from April through August, with the pace of growth quickening to 5.6% yoy in August from 4.8% yoy in July. In comparison, retail trade in August posted its first year-on-year increase of 2020 but was up only 0.5% yoy, following an annual decline in July of 1.1% (figure 1). This is in stark contrast with developments in Europe and the US, where the industrial sector has lagged in the post-Covid-19 recovery.

Thus, while the recovery in China’s GDP growth has been impressive and shows that on the whole the authorities are very much capable of directing the economy through a crisis, the nature of the recovery does highlight long-standing concerns about China’s approach to stimulus. Specifically, the concern is that China’s overreliance on debt-led growth, which has typically been orchestrated through state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and local governments, cannot sustain sufficiently high growth for China in the long run. Indeed, GDP growth in China has been steadily slowing over the past decade due to structural issues and despite a massive investment boom. Furthermore, the high importance of SEOs in the economy creates an uneven playing field for the private sector and foreign businesses. Indeed, if we look at the path of fixed asset investment since the start of the year, the recovery in investment was clearly led by SOEs (3.2% year-to-date compared to the previous year), while private sector investment has lagged (-2.8% year-to-date compared to the previous year). Despite ongoing efforts to reform and deleverage SOEs, the government turned to SOE-led investment in response to slowing growth in 2018 and 2019, and now again, it seems, in response to the Covid-19 crisis.

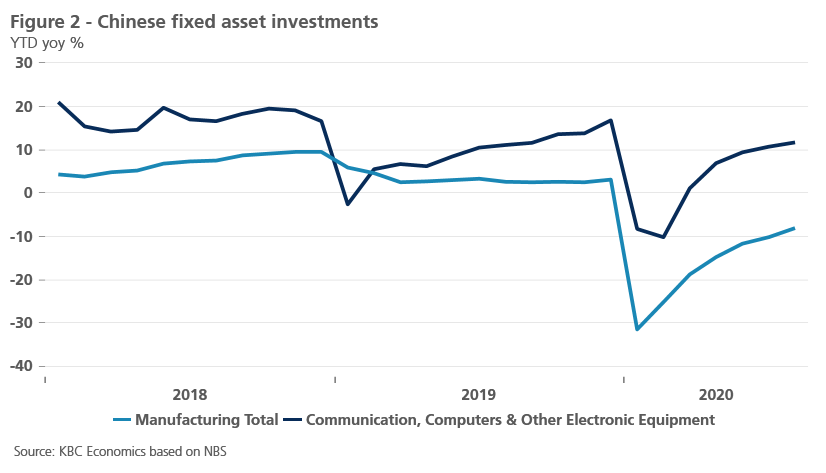

While China’s focus on investment and infrastructure as the leading drivers of the recovery has done little for the consumer side of the economy and does raise some long-standing concerns, investment in general is not typically a bad thing for an economy. It only becomes problematic when the investments are no longer productive and lead to rising debt ratios that eventually present a drag on growth. While many argue that this is the case for China, a deeper look at China’s investment data suggests that a significant portion of the investments are being made in the high-tech manufacturing sector. In particular, the manufacturing sector has accounted for more than 43% of total fixed asset investment this year, while communication, computers and other electronic equipment has accounted for the highest share (14.5%) of that manufacturing investment. Furthermore, the growth in investment in that subset of the manufacturing sector (11.7% year-to-date compared to the previous year) has far outpaced that of the manufacturing sector as a whole (-8.1% year-to-date compared to the previous year) (figure 2). This is consistent with China’s transition to higher quality growth and higher value-added exports, as well as its emerging role as a technological powerhouse.

Furthermore, there is likely an enormous role for productive investment in China if the authorities follow up their recent pledge to make China carbon neutral by 2060 with concrete steps in the near future. Of course, there are reasons to doubt whether China will deliver on its pledge. First, the new climate goal is likely in part a geopolitical move to highlight the United States’ isolated stance as it leaves the Paris Agreement. Second, China hasn’t necessarily followed through on past climate-related initiatives, like setting up an emissions trading system. Third, China hasn’t yet specified its short-term goals for reaching carbon neutrality by 2060, which means real action could still be several years off. In contrast, the European Commission’s current initiative to redefine its 2030 target to a 55% reduction in emissions relative to 1990 is aimed at balancing out the pathway to carbon neutrality by 2050 so that the adjustment after 2030 will be less severe.

But if China does follow through with a more ambitious climate plan (which will likely become clear when China announces its next five-year plan in the spring), this would require significant investments in renewable energy and other initiatives to capture or offset its carbon emissions. Thus, it is too simple to say that China’s investment-led recovery is a problem. While in the long run China does need to boost consumption to sustain high levels of economic growth, and there are many hurdles to achieving this goal, investment will of course have an important role to play as well. And the current focus on innovative investment should contribute to the transition to ‘higher quality’ growth. Hence, while there are risks surrounding China’s remarkable post-Covid-19 recovery, there are few reasons to ring the alarm bells just yet.