Can the EU’s carbon tariff boost China’s emissions reduction?

As the world’s largest greenhouse gas (GHG) emitter, China’s role in mitigating climate change will be crucial. Though China has established a policy goal of reaching carbon neutrality by 2060 and has launched its own national Emissions Trading System (ETS) this year, some doubt whether the Chinese ETS will successfully reduce emissions in the near term. At the same time, however, the EU is pushing forward with its own climate initiatives through the EU Green Deal. Most recently, this includes a proposal for a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) that aims to prevent carbon leakage as a result of higher carbon pricing in the EU compared to trading partners. Given that the EU is currently China’s second largest export market after the US, the looming threat of a carbon border tax in the EU could incentivize the Chinese authorities to make the Chinese ETS more effective at reducing emissions.

A global issue requires global action

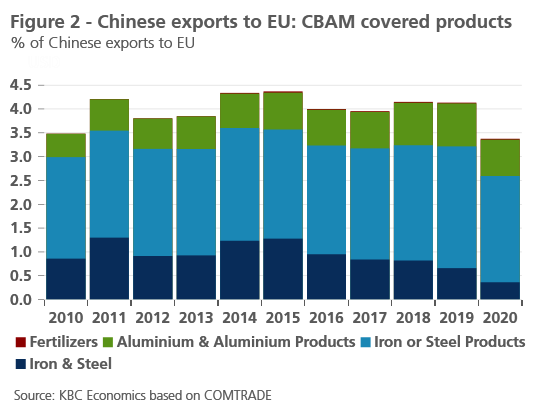

The climate crisis is a global problem that requires coordinated action from all the major economies in the world. However, despite the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2015, not all economies are moving at the same pace toward achieving their climate goals. The EU has long been a global leader on sustainability, first with the introduction of the EU emissions trading system in 2005 and most recently with the proposed overhaul of its climate agenda and targets under the Green Deal (now targeting a 55% reduction in emissions by 2030 relative to 1990 levels and carbon neutrality by 2050). But non-EU countries have also begun to step up their climate agendas in recent years, including China (figure 1).

On the surface, China’s new commitment to sustainability and the launch of an emissions trading system this year is great news. As of 2019, China accounted for 30% of global emissions. And while the EU and US have seen a slight decline in annual CO2 emissions over the past decade, China’s emissions have only continued to rise. However, there are reasons to doubt how aggressively China will pursue its stated climate goals. First, China’s ambition for reducing emissions is much more muted in the near term compared to that of the EU. In fact, China doesn’t expect to see a peak in its GHG emissions until 2030, and it is only after that its goal is to bring emissions down to reach carbon neutrality by 2060.

Design flaws

Second, the initial design of the Chinese ETS itself may not necessarily lead to a reduction in emissions. For now, the ETS only covers the power sector, though it was previously expected to cover other sectors such as petrochemicals, steel, and aviation. That in itself isn’t a major issue, as 60% of China’s electricity production still comes from coal, and the ETS is therefore estimated to cover roughly 40% of China’s emissions (which is on par with the coverage of the EU ETS). However, the Chinese ETS is only a quasi-cap-and-trade system, with no actual cap on emissions. Instead, the authorities are targeting the emission intensity of production, with benchmarks set for different producers, and free allocations given based on those benchmarks. In theory, producers could therefore meet or beat their emission intensity targets but still emit more if overall production increases. It is not necessarily surprising, therefore, that since trading launched in July, volumes have been relatively low and the price per tonne CO2 equivalent has been consistently below EUR 7.00. For context, the EU ETS allocation price has averaged around EUR 56.00 for the past three months.

But design can change

However, one shouldn’t despair just yet that the Chinese ETS will be completely ineffectual. In fact, there are many parallels that can be drawn between the early stages of the EU ETS and the Chinese ETS as it is designed now. For example, at its outset the EU ETS allocated all emissions permits for free, and the allocations exceeded demand leading to a surplus. But over time, the design of the EU ETS has been refined and the allocations reduced at an increasing pace. And under the EU’s Fit for 55 proposal, the EU ETS would become even more aggressive in terms of the pace of allocation reductions, the phasing out of free allocations, and the inclusion of additional sectors within the ETS (or offshoots of the ETS) (for further details see Box 2 – Fit for 55: a concrete climate proposal in the KBC Economic Perspectives of September 2021).

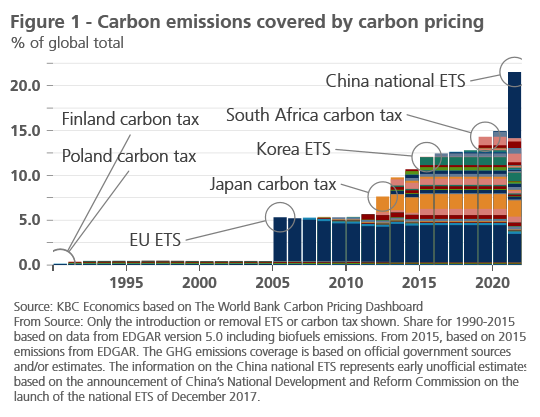

As part of the Green Deal agenda, and consistent with the stricter ETS proposal, the European Commission is also proposing a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). The goal of the CBAM is to avoid carbon leakage due to higher carbon pricing, which would undermine EU competitiveness and could offset the emissions reductions made within the EU. The CBAM would subject the import of certain products (cement, iron & steel, aluminum, fertilizers, and electricity) to equivalent carbon pricing had they been produced domestically under the EU ETS. It would be introduced in 2023 and fully phased in by 2026.

Not only do the Fit for 55 Package and the CBAM signal that the EU’s carbon pricing system is becoming an increasingly important and binding policy tool, they also signal a new progression in the EU’s status as a carbon pricing leader. With the CBAM on the horizon, the EU’s trading partners, particularly for the products covered by the mechanism, will have to be more conscious of the emissions content of their goods (where actual emissions are not reported, importers will have to pay based on default values). And the fact that the price paid can be reduced if the carbon content of the good was already partially paid for outside of the EU, could provide an additional incentive (aside from a country’s own sustainability goals and pledges) for other jurisdictions to enact or strengthen their own carbon pricing schemes.

China may fall into this category, as the EU is China’s second largest export market. And though the covered products only account for about 4% of China’s exports to the EU (figure 2), it is not hard to envisage the EU eventually expanding the coverage of the CBAM to further sectors or downstream. Hence, aside from achieving their own sustainability goals, the Chinese authorities have a clear, growing incentive to strengthen the framework of their newly launched ETS. And, of course, China is not alone in facing such incentives. The EU has established itself as a frontrunner on climate policy, but the global trend is clear. Climate initiatives like carbon pricing are only growing increasingly more important.