Belgium needs major public investment wave

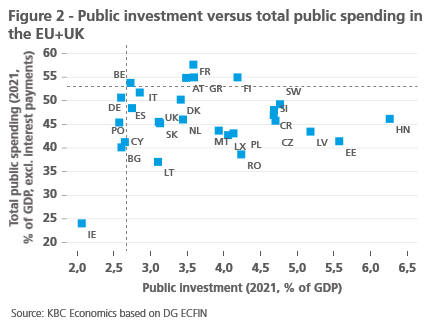

The Belgian government has been under-investing for decades. Within the EU, Belgium is among the countries with the lowest public investment. This is particularly painful because the country ranks among the top European countries in terms of total public spending. The catch-up operation initiated with the recovery plans is likely to be insufficient to reach the intermediate target for public investment (3.5% of GDP in 2024). Part of the problem is that the distinction between ‘real’ investment and current spending is sometimes remote in fiscal policy. Meeting the 4.0% target by 2030 will require a more ambitious investment policy. Given the lack of fiscal space, this implies a curtailment of (less essential) current spending in favour of investment.

In the National Accounts, government investment is defined as ‘gross fixed capital formation’ by the government. The term gross refers to the balance of purchases and sales made of assets. The latter are both tangible (e.g., buildings, highways or sewers) and intangible (e.g., education or R&D). In 2021, investment spending by the general government in Belgium amounted to 2.7% of GDP. According to a broader definition, investment also includes investment contributions paid by the government to entities of the non-profit sector (e.g., hospitals or residential care centres), which fulfil a mission of general interest but are not part of the public sector in the narrow sense. In the broad sense, public investment amounted to 3.8% of GDP in 2021.

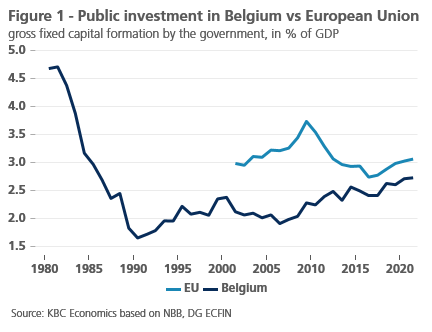

To look at the evolution of public investment over a longer period and against other countries, the narrow definition is usually used. After peaking in the 1960s and 1970s (at 4-5% of GDP), public investment in Belgium fell sharply during the fiscal consolidation of the 1980s, to well below 2% of GDP in the early 1990s. Since then, it has fluctuated between 2 and 2.5% of GDP, with modest trend increases over the past decade (see figure 1). Due to the lack of investment, the Belgian government’s net capital stock steadily eroded from 50% of GDP in 1995 to around 40% today. In other words, new investments could not compensate for the wear and tear or depreciation of the government’s capital stock from previous investments.

Even compared to other European countries, the situation is not good. Belgium has long been and still is among the group of countries with the lowest public investment. The comparison becomes even more striking when public investment is set against total primary public spending (i.e., excluding interest payments). Belgium stands out within the European Union for its combination of weak public investment and high overall public spending (see figure 2). Governments in most countries manage to invest more than Belgium while spending (much) less overall. For Belgium, this is reflected in a relatively low share of public investment in total primary public spending of only 5% in 2021.

Public investment can have a general or specific social purpose (e.g., to purchase military equipment, build social housing, or prepare the country for challenges such as climate change). Often, investments are made for productive purposes (e.g., in transportation or port infrastructure). Overall, public investment is of great economic importance. In the short term, an increase in it creates a positive demand effect in the economy. Indeed, public investment is part of spending and thus has a direct upward impact on GDP. In the longer run, public investment can strengthen the supply side of the economy by increasing overall productivity. In this sense, it has a beneficial effect on the economic growth potential.

Of course, not every investment has large positive growth effects. It is important for the government to focus on the investments with the greatest multiplier effects. The literature shows that the productive capacity and efficiency of the economy is mainly stimulated by investments in infrastructure, education, research and innovation (see, e.g., NBB report ‘Public investment: analysis and recommendations’, 2017). In general, that kind of investment creates a favourable environment within which it pays for companies to invest, innovate and create jobs. Important concrete, current spearheads in that regard are public investments in mobility, energy and digitalization.

Gearing up

Since the pandemic, there has been growing awareness among the government that something needs to be done in terms of its investments. In the policy statement at the end of 2020, the government set the goal of increasing investment to 4% of GDP by 2030, with an interim target of 3.5% by 2024. According to the Federal Planning Bureau’s latest medium-term outlook (June 2022), while public investment would increase in the coming years, driven by the various recovery plans, defense spending and the electoral cycle of the lower government, it would remain below target at 3% in 2024. Thereafter, in the absence of new stimulus, public investment would even fall to 2.7% in 2027, i.e., the 2021 level.

This illustrates that the government needs to step up to effectively meet the 4% target. By the way, it is not just the figure that is important; there must also be a focus on sufficient ‘productive’ public investment that supports the longer-term economic growth potential. This requires, among other things, that investment be properly distinguished from other, current public spending. Recently, we have seen a certain dilution of the concept of public investment. Indeed, politicians tend to label certain current expenditures, such as those in care or pensions, as an investment (“in people”) as well. This is not to say that those public expenditures are not important, often quite the contrary. But the risk of diluting the concept of public investment is that it undermines the equally important economic purpose behind public investment. The new Supreme Council on Public Investment to be established could play a role here to more clearly delineate the ‘real’ investment effort.

Finally, in the absence of fiscal space, it will be necessary to curtail certain (less essential) government current expenditures in favour of investment in the coming years. This mainly implies making further efficiency gains in public administration and a stronger policy focus on what is really important in society and the economy. By all means, it must be avoided that the future, necessary consolidation of Belgium’s public finances comes at the expense of investment. In the past, scaling back public investment has too often been seen as a politically convenient saving, because it directly affects few people’s income or jobs. But economically, that is short-sighted.