Behind China’s positive growth surprise, a balance-sheet recession still lingers

China’s Q3 GDP figures surprised to the upside at 4.9% yoy, setting the economy up to reach the government’s 5.0% growth target in 2023. Relative to 2022’s poor growth outturn (of 3.0% due in large part to zero-covid), a rebound of 5.0% wasn’t very ambitious, and focus now turns to 2024, where much depends on the trajectory of China’s domestic consumption and relatedly, the real estate sector. Back in 2019, we highlighted that China’s high household debt level presented a structural challenge for domestic demand and noted that “a collapse of the real estate market in China would have grave consequences for several aspects of the Chinese economy, including consumption growth.” Real estate hasn’t quite collapsed, but it is certainly in crisis, and the crisis is keeping consumer confidence extremely weak, leading to speculation that China is entering a so-called balance sheet recession. While signs point in that direction, China’s situation is unique. E.g., an aging population and a weak social safety net also contribute to China’s high savings and weak consumption rates. And on the corporate side, the need for deleveraging comes mainly from the quasi-public sector of SOEs and LGFVs, meaning the usual policy prescription of using fiscal stimulus to counterbalance the private sector’s deleveraging needs to be somewhat more nuanced. Indeed, fiscal policies that support the switch to consumption as a major driver of growth are needed now more than ever, but with the growth target in reach, substantial policies and reforms seem even less likely.

The term balance sheet recession was coined by economist Richard Koo and gained traction during Japan’s economic stagnation in the 1990s. It refers to a situation in which a debt-financed asset bubble bursts, the private sector enters a period of deleveraging, monetary policy therefore becomes ineffective because lower interest rates still do not incentivise the private sector to borrow, and fiscal policy therefore becomes key.1 In many ways, China’s current situation fits the bill. A spree of debt-financed investment in infrastructure and real estate over the past two decades pushed the real estate sector to be a significant growth driver while the debt levels of the corporate and household sectors rose rapidly (for details see: Debt, decoupling, and diversifying growth: China’s many challenges). Just as tighter monetary policy helped tip Japan’s real estate sector into a tailspin and set off a so-called lost decade, Chinese policymakers inadvertently triggered a liquidity crisis among property developers when they tightened borrowing requirements in 2021. While China’s policymakers have since reversed course, lowering interest rates and trying to incentivise borrowing, demand for credit appears to be lacking. Together with increased savings, it seems the household sector is focused on deleveraging as fears of a sharper correction in house prices grow.

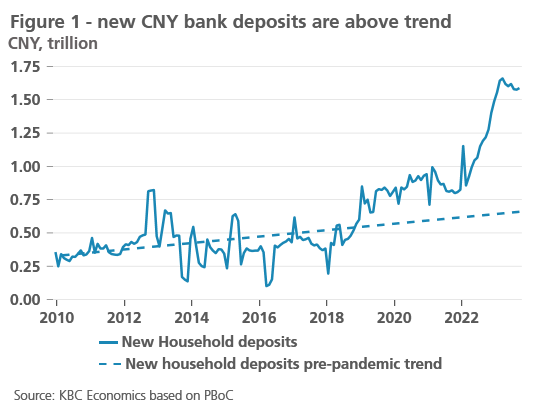

There are two important things to keep in mind. First, though households appear to be deleveraging, China’s household sector has long tended to over-save. In 2022, gross national savings amounted to 46% of GDP, compared with a world average of 28%, according to IMF data. The same is true for Chinese households in particular; net household savings amounted to 35% of net disposable income in 2019 (latest available OECD data) compared to 9% in the US, 6% in the EU, and 3% in Japan. The three latter economies all saw a surge in savings in 2020 due to the pandemic that has since been unwinding. We don’t have new data for China, but household bank deposits can serve as a proxy. They surged around the onset of the pandemic, but accelerated even further in 2022, as the real estate sector problems began to have noticeable impacts on the real economy, which also coincided with strict covid lockdowns. Though the surge has stopped, household deposits remain stubbornly high (figure 1). Hence, confidence in the real estate sector does appear to be having an impact on savings in China, but longer standing issues (such as improving the social safety net) also need to be addressed to help induce a rebalancing away from savings and towards consumption.

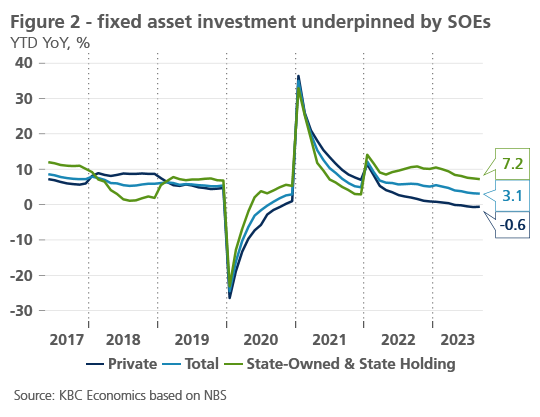

Second, much of the rapid rise in corporate sector debt since 2008 can be attributed to the state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs). According to Koo, during a balance sheet recession, the public sector needs to run a budget deficit to prevent an extended economic stagnation. But relying on the quasi-public sector of SOEs and LGFVs to support economic activity has long been part of China’s playbook despite evidence that the SOEs are relatively less efficient and are weakening China’s business dynamism.2 Furthermore, the LGFVs are reportedly running into increasing problems regarding debt sustainability, and according to the IMF, need a comprehensive restructuring.3 Furthermore, a breakdown of fixed asset investment shows that SOEs have already been doing the heavy lifting in the economy compared with the private sector for some time, yet it hasn’t been enough to prevent mostly underwhelming growth outcomes (figure 2).

Hence, while there are parallels to China’s current situation and other balance sheet recessions, there are also important differences. Fiscal policy likely is the key tool the Chinese authorities need to use to bolster growth, but relying on old habits of directing investments through increasingly inefficient SOEs and increasingly overleveraged LGFVs will not fix China’s problem. China needs fiscal stimulus geared toward supporting private sector enterprises and Chinese households instead. With the government growth target in reach, however, major policy changes are unlikely, which doesn’t bode well for China’s medium-term economic outlook.

1. Richard Koo, 2011. "The World in Balance Sheet Recession," Ensayos Económicos, Central Bank of Argentina, Economic Research Department, vol. 1(63), pages 7-39, July - Se.

2. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2022/02/18/China-s-Declining-Business-Dynamism-513157

3. https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/002/2022/022/article-A003-en.xml#A003fn01