Another negative shock for Asia

The novel coronavirus outbreak (Covid-19) that started in December in Wuhan, China, is expected to have a sizable effect on China’s economy in 2020. As noted in an opinion last week, several European countries could be vulnerable to a negative demand shock in China. For Asian economies, the story is even more concerning. Economies in the region are more deeply integrated with China through both value chains and a higher reliance on Chinese final demand. What’s more, the region is coming off of a difficult period, with weaker growth and trade developments in 2019 reflecting the effects of the US-China trade war and a downturn in the high-tech chip industry. Positive signals at the end of 2019 and beginning of 2020, such as improvements in manufacturing sentiment and the start of a recovery in global semiconductor sales, have not disappeared, but they are being overshadowed by the spread of the coronavirus for the moment. Recent reports suggest the virus is spreading more intensively outside of China (particularly in South Korea, Italy and Iran) but the World Health Organization has yet to declare the coronavirus as a pandemic. However, even if the vast majority of cases remain contained to China, the economic impact will be felt further afield in the short term, especially in Asia.

Slower growth for China

The spread of Covid-19 continues, with confirmed cases in

Mainland China surpassing 78,000 and cases in other countries reaching

nearly 3,000 as of 26 February. The Chinese authorities have taken

sweeping steps to try and contain the virus, including putting entire

cities under lockdown, drastically cutting transportation, and

extending the holiday period to keep factories closed and workers at

home. Outside of Wuhan, some factories and offices have started to

reopen, but reports of staff shortages suggest disruptions are still

the norm. Several sectors will see a deterioration in growth, such as

tourism, retail trade, transportation, real estate, and general

consumer demand. Given factory closings, industrial production is also

likely to take a hit. Indeed, vehicle production, which recovered in

the second half of 2019, contracted 24.6% yoy in January. Under the

assumption that the spread of the virus peaks sometime in the first

quarter, we expect Chinese growth to slow considerably in Q1, before

partially recovering in Q2 and then returning to its long-term growth

path in Q3.

Regional economies will feel it too

This growth disruption will have spillover effects for a number

of Asian economies, particularly in the short term. Though over the

past decade or so China’s backward participation in global value

chains has declined, the country’s importance to global supply chains

should not be underestimated. China’s GDP as a share of world GDP

increased from 3% in 1998 to 16% in 2019, while its share of world

trade similarly expanded from 3% to 14% over the same period.

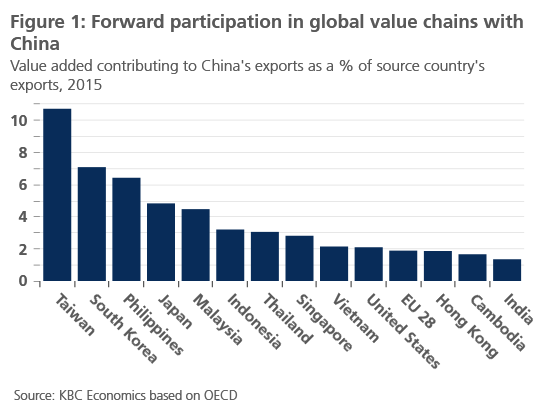

Furthermore, from the perspective of individual economies, especially

other Asian economies, China is a key partner for their forward global

value chain participation. Figure 1 shows the value-added originating

from each country that is found in China’s exports, measured as a

share of the originating country’s exports. This figure is

particularly high for Taiwan (11%) but also not insubstantial for

South Korea (7%), the Philippines (6.4%), Japan (4.8%) and Malaysia (4.5%).

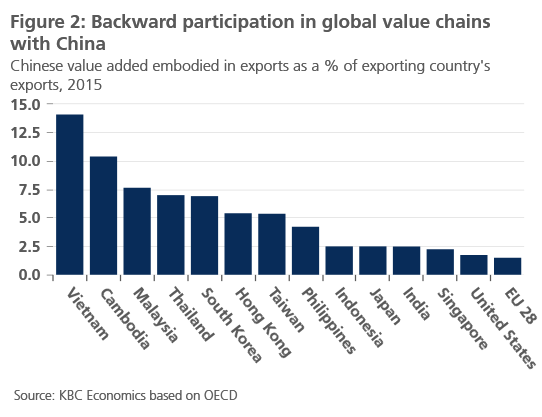

China has also increased its forward participation in global

value chains since 2009, which is consistent with China’s aim of

focusing on higher value added (high-tech) exports. It also means that

China is exporting more intermediate goods to other countries. This is

why extended disruptions at Chinese factories could disrupt supply

chains and cause problems for businesses that rely on Chinese

suppliers. As Figure 2 shows, value added from China accounts for more

than 5% of exports for at least seven Asian economies, and over 10%

and 14% for Cambodia and Vietnam, respectively. Though there is also

supply chain integration between China and the EU or the US, the

extent of this integration is smaller than for most Asian economies.

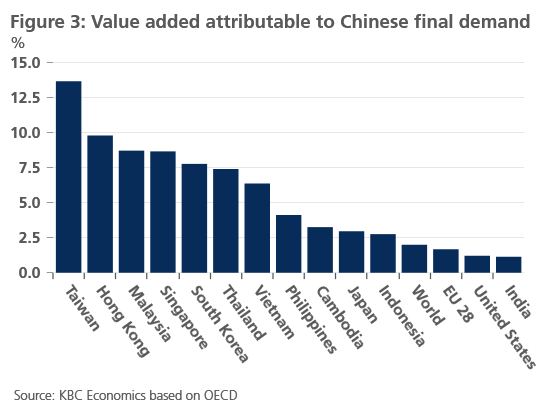

Finally, a number of countries in the region are, to some

extent, dependent on final demand from China (Figure 3), which is

consistent with China’s growing consumer market and its growing

wealth. In Hong Kong, for example, value added embodied in China’s

final demand accounts for almost 10% of Hong Kong’s total value added.

This can likely be attributed to tourism, as Hong Kong is the top

destination for Chinese tourists, but also to financial services. For

Taiwan, in contrast, this figure is nearly 14%, and can be attributed

to the enormous amount of electronics Taiwan exports to China (Taiwan

is China’s third most important import partner).

It therefore becomes clear that the economic disruptions in

China will likely have important implications for other economies in

the region, at least in the short term. The slowdown in China’s

consumer demand will impact those economies that rely heavily on final

demand from China, while those with important supply chain linkages

may face additional challenges. The positive signals coming out of

Asia prior to the outbreak haven’t vanished, of course, and

authorities in vulnerable economies are responding with monetary and

fiscal stimulus measures. Once the outbreak comes under control, the

region should continue to benefit from an improving external

environment in which trade tensions have eased and important sectors

for the region are experiencing a recovery.