American protectionism is not a one-day thing

One of the main reasons why prospects for the global economy are deteriorating is the US trade war. On the eve of the G20 summit in Osaka, many continue to hope for a rapprochement between the US and China that will eventually lead to a new agreement, including a structural solution to the US trade deficit with China and solid international protection of intellectual property. Anyone who hopes for a quick end to the encroaching protectionism will be disappointed though. We are experiencing a rise in protectionism in the longer term. American trade policy in particular is systematically becoming less open. Not only China, but also other American trading partners are affected. In addition, other countries also engage in similar practices. Protectionism will continue to influence the global agenda as an economic and political weapon for a long time to come.

When President Donald Trump, at his inauguration, threatened China with tariff increases, few could have imagined that those first protectionist threats would lead to a rapidly escalating and far-reaching American-Chinese trade dispute. Now, the US is threatening higher tariffs on the remaining USD 300 billion of Chinese imports, which are currently exempt from increased US tariffs. But it is not only China that is the target of American trade policy. Previously, the US government introduced higher tariffs on steel and aluminium, affecting most of their trading partners. The US, Canada and Mexico also renegotiated the NAFTA trade agreement. In the new USMCA trade agreement, free trade is restricted by all kinds of artificial interventions that, for example, are intended to limit Mexico's labour cost advantage.

But the assertive American trade policy affects many more countries, which often remain under the public radar. In June alone, the US International Trade Commission launched an investigation into off- road tires, mattresses and crawfish tail meat from China, glycine from China, India and Japan, stainless steel kegs from China, Germany and Mexico, Mexican tomatoes and Turkish dried tart cherries, among other things. Such investigations often result in anti-dumping or anti-subsidy measures. This has long been a common practice in US trade policy. Officially, these are protective measures that are perfectly justifiable under the rules of the World Trade Organisation, subject to the necessary argumentation and burden of proof. After all, unfair international pricing or subsidisation disrupts the free market operation. Victims of such trafficking have the right to defend themselves against it.

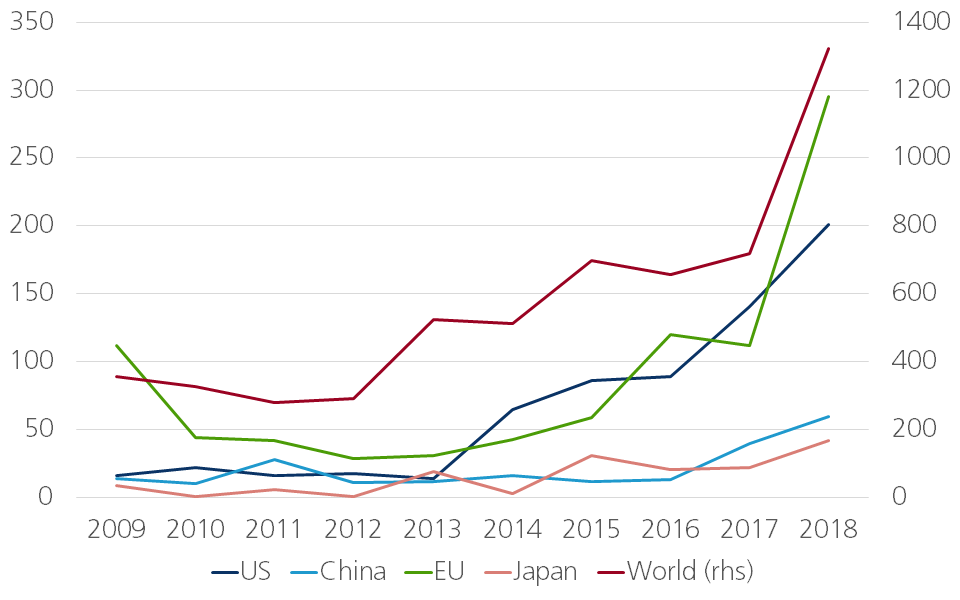

However, it is noticeable that such a defensive trade policy has grown enormously in recent years. Not only the Trump Administration, but also the Obama Administration was very active in this area. Figure 1 shows that the number of US measures harming international trade has consistently exceeded the number of liberalising initiatives for many years. This trend has accelerated in recent years under President Trump's policy.

Figure 1 – Number of new US trade interventions affecting all countries

The major difference with the past is that the US is increasingly using its trade policy for non-trade purposes. President Trump's threat to systematically increase US tariffs on Mexican imports until Mexico accepted a migration agreement is a clear example of this. Conversely, the offer to the United Kingdom to conclude a favourable trade agreement with the US in the event of a no-deal Brexit is an influence on a foreign policy process. Of course, historically, trade and politics have always been closely related. But the openness with which trade policy is currently used, or rather abused, to achieve political goals is unparalleled. The problem with such a policy is the high uncertainty it creates for international business. After all, companies make decisions about international investments and trade contracts on the basis of a long-term strategy. Protectionist measures often distort current trade flows, but uncertainty also weighs on future investments.

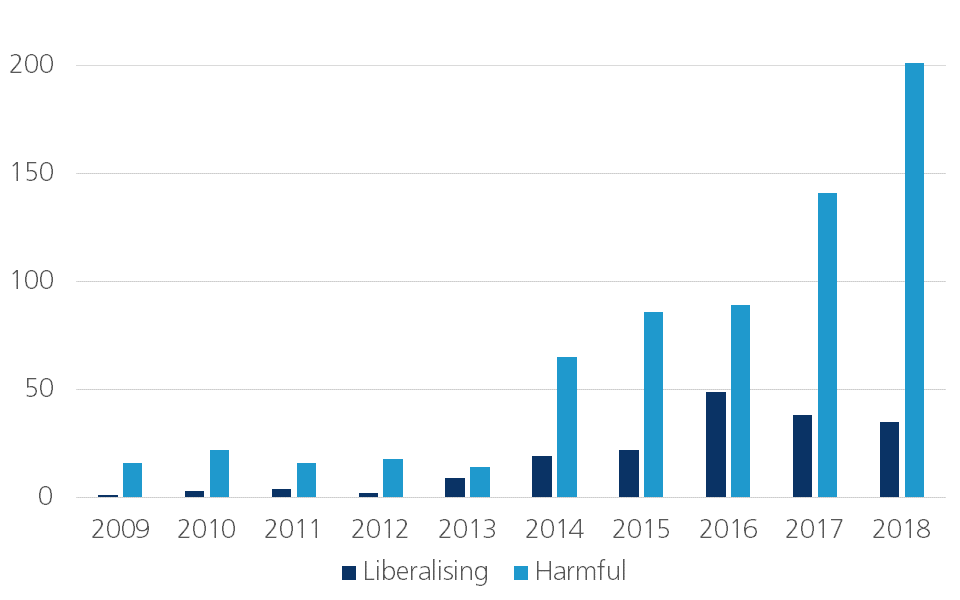

All major American trading partners are victims of the new wind blowing through the White House. The spotlight is most often on measures against China, but Mexico, Canada, Japan and the EU are also increasingly affected (figure 2). This does not bode well for the future. Anyone who hopes for a rapid de-escalation in the American-Chinese conflict and a general cooling down in the American trade war will probably be disappointed. Rather, the figures show that a protectionist trade policy is the basic recipe for current US economic and political policy. Even if bilateral conflicts do not lead to hard confrontations, the protectionist undercurrent will influence the world economy for a long time to come. Globalisation and free trade are no longer self-evident.

Figure 2 – Number of new harmful US trade interventions affecting…

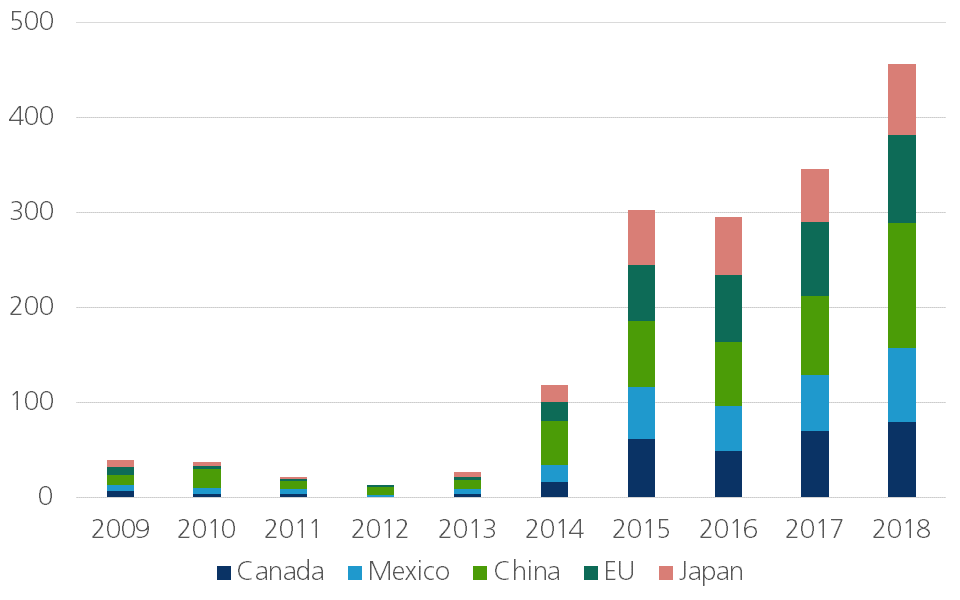

Should we only point to the United States with an accusing finger? Absolutely not. The US sets the tone, but figure 3 shows that we are dealing with an international trend. Protectionism is growing in all major economies (see also KBC Economic Opinion of 25 January 2019). The EU certainly is not above fault.. Of course, this increases the risk of a rapid escalation of trade disputes. Protectionist initiatives are answered by protectionist countermeasures. Historically, this insight led to the establishment of the World Trade Organisation as an international negotiating forum and arbitrator. More than ever, we need a strong international institution to put our house in order.

Figure 3 – Number of new harmful trade interventions affecting all countries implemented by…