Emerging market vulnerabilities and weaknesses

- Why are emerging markets in the spotlight?

- Which countries have the highest imbalances?

- What are the consequences?

Read the publication below or click here to open the PDF

Emerging markets have taken a beating in recent months. Though turbulence in Argentina and Turkey—whose currencies have respectively lost 54% and 39% of their value against the USD this year—have dominated the headlines, they are not the only emerging markets to face increased market volatility. Such volatility in emerging markets is common when the Federal Reserve is in the middle of a policy tightening cycle. Indeed, with interest rates in the U.S. rising and expected to rise further, some emerging markets may find it more difficult to secure (re)financing from international capital markets. Furthermore, a loss of market confidence and associated pressure on a country’s currency can have sizable repercussions for growth, especially when financial stability considerations push central banks to raise interest rates. Therefore, it is worth considering the vulnerabilities of several emerging markets and possible implications of further market turbulence.

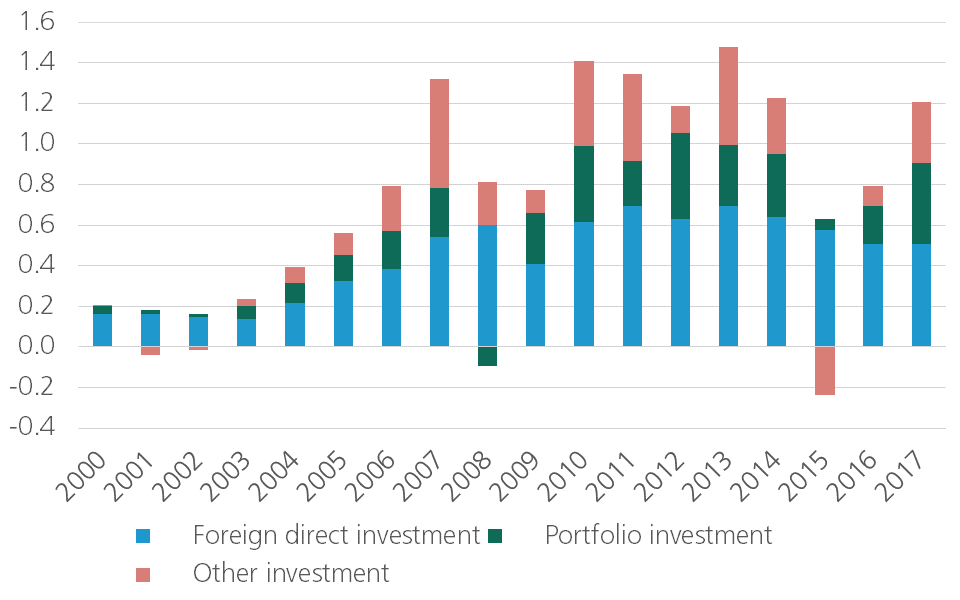

For years after the financial crisis, major central banks such as the Federal Reserve and the ECB lowered interest rates to zero (or even negative) and implemented unconventional, quantitative easing policies. During this period of very easy financial conditions, emerging markets also had notably easier access to financing. Capital flows to emerging markets recovered and, save for a dip in 2015-2016, remained strong until recently (figure A). Furthermore, many emerging markets racked up sizable debt positions, some of which are denominated in foreign currency.

Figure A - EM Non-Resident Capital Flows (USD tn)

Now, however, the Federal Reserve is in the midst of a hiking cycle and is winding down its balance sheet, which had grown substantially thanks to quantitative easing. The ECB is also set to end its monthly Asset Purchase Programme by the end of 2018, though a first rate hike isn’t expected until after summer 2019. With global interest rates rising, a stronger USD, and financial conditions tightening, markets appear to be reconsidering whether ‘search for yield’ behaviour may have led to a misallocation of funds in previous years.

Reflecting such concerns, net capital flows to emerging markets have dropped off since the beginning of the year. A sudden decline, or even reversal of capital flows and more limited access to international financing means that a country has to very quickly adjust its macroeconomic imbalances, such as its current account deficit or fiscal deficit. When market forces necessitate an abrupt adjustment of a country’s current account deficit, for example, this either requires a decline in imports or an increase in exports. Of course, a weaker currency helps in both regards. As such, it is not surprising that the currencies of those emerging markets with the largest imbalances have generally come under the most pressure this year.

Not all sources of financing to emerging markets are the same however. As seen in figure A, foreign direct investment (FDI) tends to be much more stable than volatile portfolio investment. Countries that are more reliant on portfolio flows, therefore, are more vulnerable to a sudden shift in risk sentiment. Furthermore, fears of further losses on emerging market assets may spur holders of that country’s debt to either sell the assets or hedge their currency exposure, putting additional pressure on the currency. This means that countries with a higher proportion of debt held by non-residents are also more vulnerable.

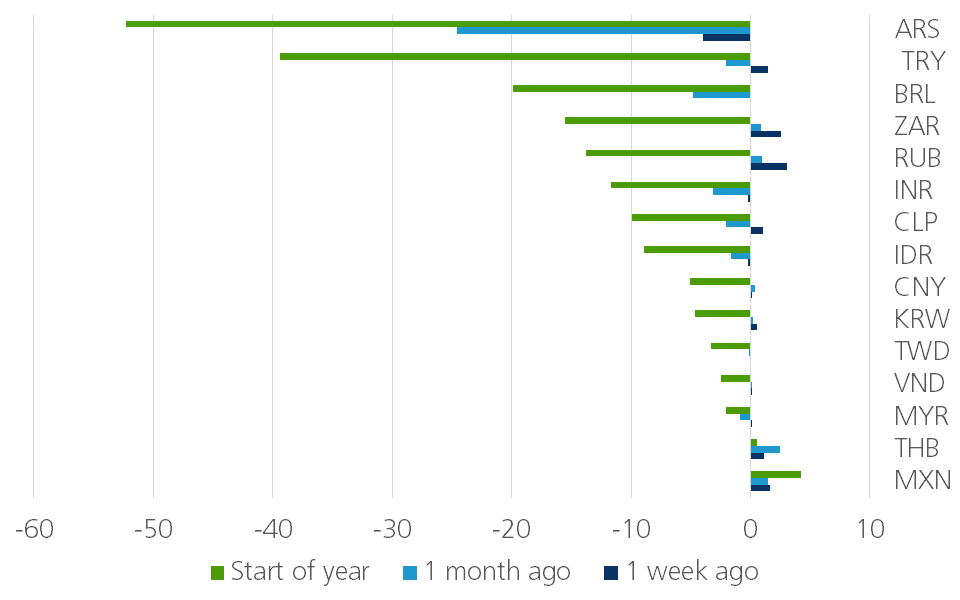

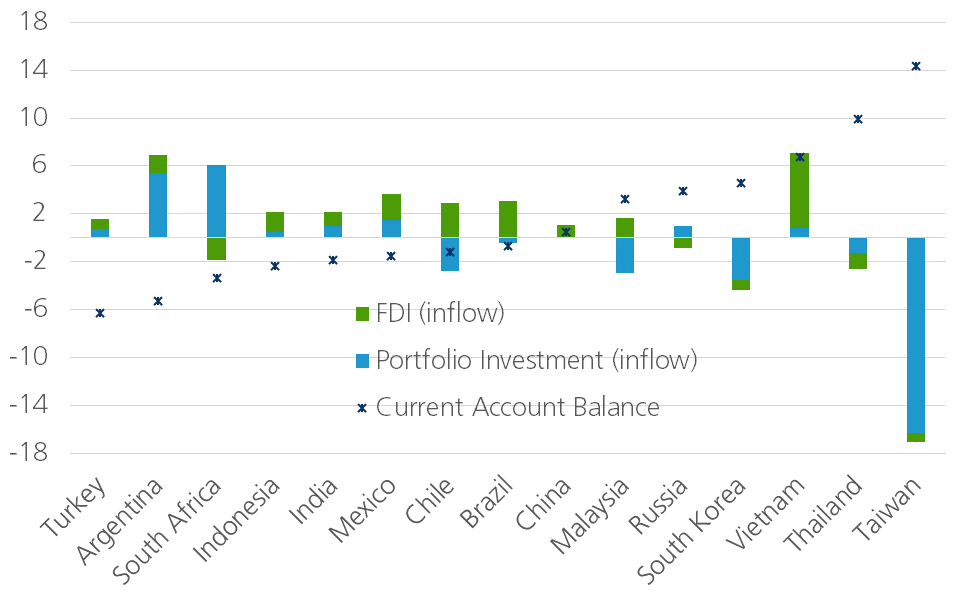

As seen in figure B, the Argentine peso (ARS), Turkish Lira (TRY), Brazilian real (BRL), South African Rand (ZAR), Russian rouble (RUB), Indian rupee (INR), Chilean peso (CLP) and Indonesian rupiah (IDR) have all depreciated significantly against the USD this year (~9% or more). In many cases, the central bank and authorities have had to intervene to stabilize the currency. Though of course, idiosyncratic factors are at play for countries like Argentina and Turkey (i.e. a legacy of debt defaults and an erosion of policy norms, respectively), each of these economies have notable imbalances or weaknesses related to their financing needs. In terms of the balance of payments, for example, Turkey, Argentina, South Africa and Indonesia, all have current account deficits larger than 2.0% of GDP. Furthermore, Argentina and South Africa have a notably high reliance on portfolio investment (figure C).

Figure B - Change in emerging market currencies vs USD (in %, as of 18 September 2018)

Figure C - Balance of Payments, 4Q-rolling (% of GDP)

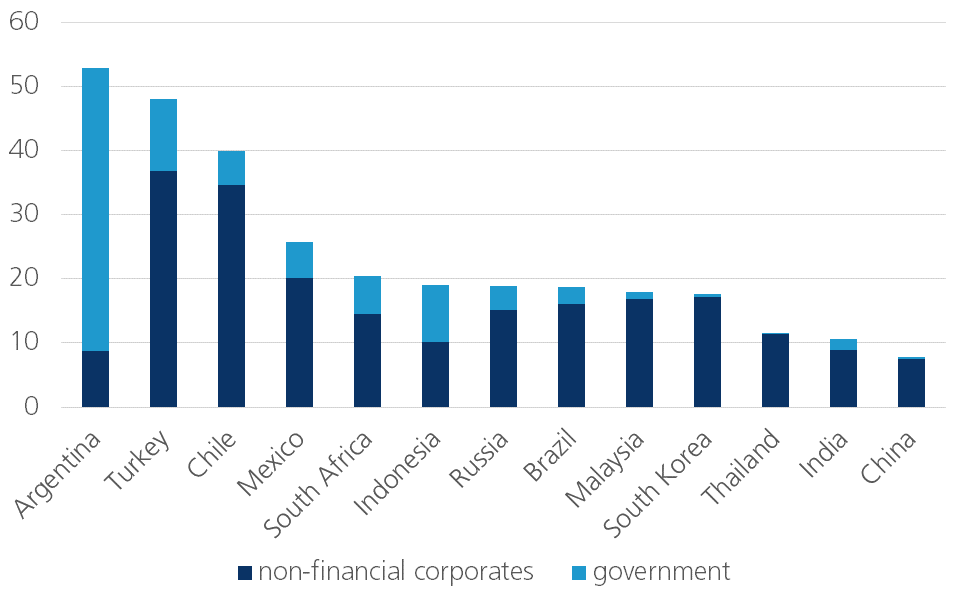

Several of the countries whose currencies were hardest hit in recent months also have either sizable fiscal deficits, high levels of public debt relative to GDP (or both). What’s more, a non-negligible portion of that government debt, in addition to corporate debt, is denominated in USD for several emerging markets (figure D). Finally, while many emerging markets have international reserves which more than cover short-term external debt, Argentina and Turkey either fall short, or have reserves just equal to short-term external debt.

Figure D - Foreign Currency Debt, % of GDP (Q1 2018)

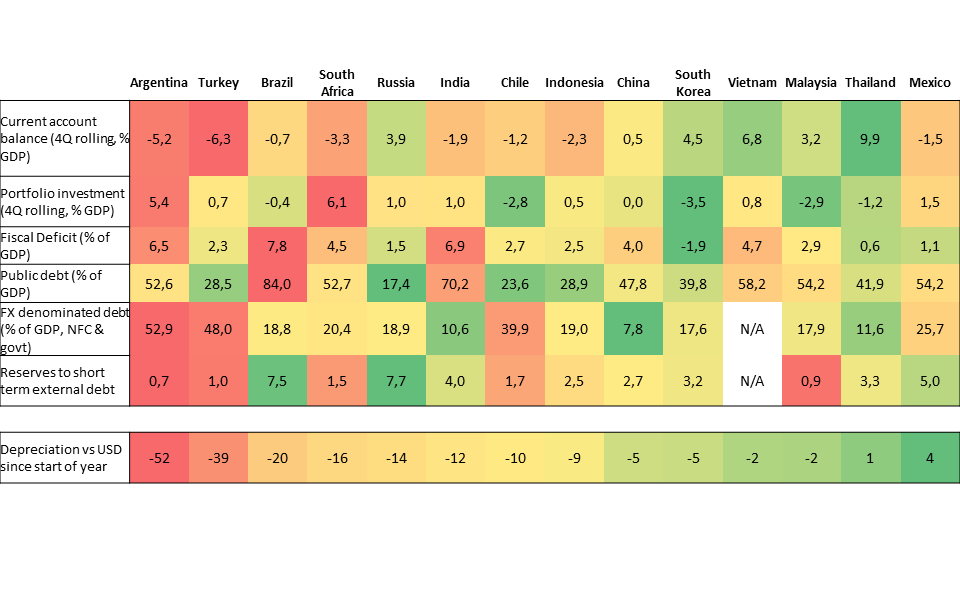

Taken together, as seen in figure E, it is not surprising which economies have endured the most market turbulence this year. It is also worth pointing out, however, that while several emerging market economies have notable vulnerabilities, those of Argentina and Turkey, which have clearly spun into crisis-mode, are far more substantial. Furthermore, for many emerging markets, several of these metrics are much stronger than compared to previous crisis periods. Indeed, the fact that most of these emerging markets now have a floating or managed-float currency, rather than one pegged to the dollar, means that the necessary adjustments can take place. Hence, though emerging markets in general have faced market pressure this year, it does not necessarily mean that crisis-like conditions will spill over to all emerging markets.

Figure E - Vulnerabilities heat map

The authorities in emerging markets do have policy tools available to combat market volatility. Indeed, in response to pressure from markets, authorities and central banks in several of these economies have raised interest rates, intervened in currency markets, and proposed new fiscal adjustments. In Argentina and Turkey, the respective central banks have raised rates a whopping 3,125 and 1,600 basis points respectively since the start of the year. They are not alone though. The Indonesian central bank has raised rates 125 basis points to combat the rupiah’s worst slide since 1998 and has intervened in the market by selling reserves and purchasing local currency denominated bonds. India’s central bank has raised its policy rate as well, while the Central Bank of Brazil cut short an easing cycle in response to weakness in the BRL.

Such actions are not without consequence, however. Indeed, a decline in capital flows, subsequent forced adjustment of macroeconomic imbalances, and rising interest rates to support the currency can all be a significant drag on growth. This weakening comes at a time when several emerging markets are already facing headwinds to growth, or only experiencing tepid recoveries which could easily be derailed by further adverse developments. Increased uncertainty due to escalating global trade conflicts, especially between the U.S. and China (but also with regard to NAFTA renegotiations and U.S.-E.U. trade relations), are also weighing on market sentiment towards emerging markets. Additional tariffs between the U.S. and China, for example, could have spill over effects for smaller Asian economies that are highly integrated into China’s export value chains.

Hence, it is likely to continue to remain a difficult period for emerging markets for some time. Given dollar strength and various lingering uncertainties, economies that still need to undertake macroeconomic adjustments will likely continue to face market pressure or weaker growth. However, it is clear that some emerging markets are in a much better position relative to their peers and market pressure doesn’t mean an economy will tailspin into crisis. The risk remains that sentiment towards emerging markets could sour completely, leading to across the board sudden stops in capital flows and plummeting currencies, but for most economies at the moment, the turbulence appears to be just turbulence.