Turkey: time to abandon Erdoganomics?

After a robust, decade-long period of economic growth, the Turkish economy has fallen into recession. While domestic demand collapsed in response to the currency crisis of mid-2018, inflation rose to 20% yoy and unemployment surged to a double-digit rate. A painful economic downturn has dealt a heavy blow to President Erdogan as his ruling AKP lost control of both Istanbul and Ankara in the local elections last weekend. Still, subsequent developments will be more important than the elections themselves; despite no indication of a rapid economic recovery similar to 2008, the end of the current election cycle promises an unprecedented four-year long election-free period. This provides room for needed structural reforms of the economy, as well as resetting relations with the West. However, abandoning Erdoganomics, a profoundly unorthodox approach to economic policy, will be a necessary prerequisite for that.

Turkish voters headed for the seventh election in five years last weekend. However, local elections on Sunday marked the first vote since the major constitutional changes and a shift towards a presidential system. This time, too, the campaign was dominated with confrontational rhetoric by the ruling AKP (allied with ultra-right MHP), framing the elections as a matter of “national survival”. Although the AKP came first nationwide (44%), the current president has suffered a heavy blow as his party lost control of the capital, Ankara, and the major economic centres Istanbul and Izmir, to the major opposition party, the CHP. This is not only a symbolic victory in Erdogan’s former stronghold, Istanbul. The opposition secured its grip over the only centre of power outside the otherwise centralised presidential system.

The struggling economy in the spotlight

One of the key reasons behind the worse-than-expected election results for AKP is without a doubt a visibly weakening economy. The key trigger was the currency crisis of late summer 2018 when the Turkish lira depreciated by more than 30% against the USD and the underlying macroeconomic imbalances – in particular, a weak external position and increased reliance on volatile short-term capital inflows – were fully exposed. As a result, for the first time in a decade, the economy fell into recession with real GDP declining by 1.6% qoq in 3Q and by 2.4% qoq in Q4 2018 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – The Turkish economy has fallen into recession for the first time in a decade

This year, we expect the economy will shrink by 0.5% (with the risks tilted to the downside) given the ongoing adjustment, including the rapid drop in domestic demand on the back of a sudden stop in capital flows and subsequent credit crunch. The spillovers to the labour market are also increasingly apparent with the unemployment rate rising above 13% – the highest level in almost ten years.

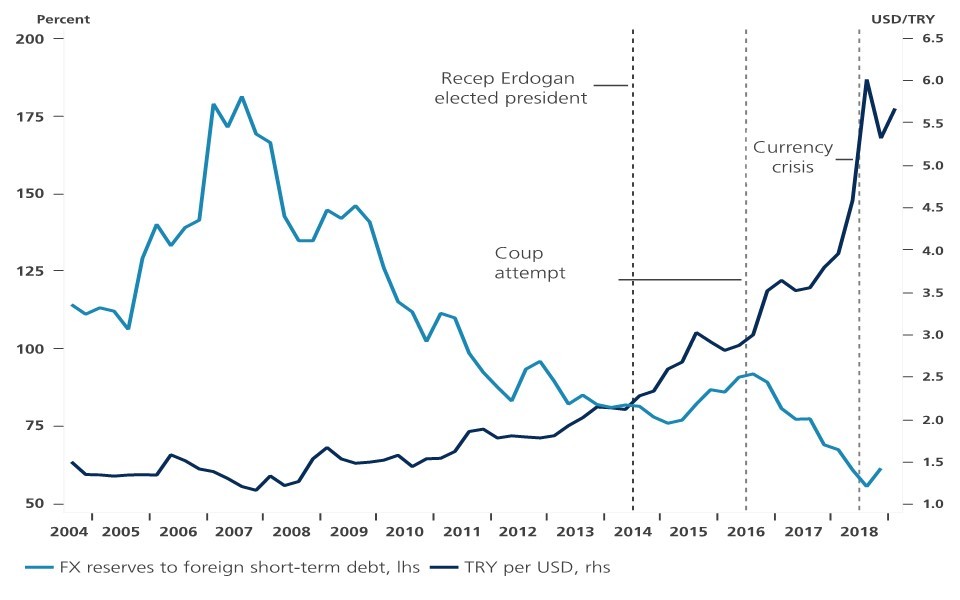

Moreover, compared to the last recession in 2008, nothing really suggests that Turkey is to experience a similarly rapid V-shaped recovery. In fact, a slower U-shaped recovery seems more likely, given that the country’s weak fundamentals have hardly been fixed and the economy remains extremely vulnerable; corporate balance sheets are fragile (and exposed to FX risk), foreign reserves are limited (the FX reserves to foreign short-term debt is below 70%), and the lira remains volatile (Figure 2). In addition, the rebalancing will take place in a more challenging external environment due to the expected slowdown across the EU, Turkey’s main trading partner.

Figure 2 – Since fundamentals have hardly been fixed, the economy remains highly vulnerable

Unprecedented room for reforms, but…

On the other hand, as the current election cycle is completed, the government has an unprecedented four-year long election-free period ahead. The authorities should use this time to introduce important structural reforms, which would help to restore household and investor confidence in the economy. A necessary condition for that, though, is to abandon the unorthodox economic policies and experiments of Erdoganomics, which put the economy into the crisis in the first place.

First of all, to rebuild its credibility, the Turkish central bank (TCMB) should be independent of political pressures, which is currently hardly the case. President Erdogan is a self-proclaimed enemy of high interest rates, which was the main reason why the TCMB delivered necessary monetary tightening reluctantly and behind the curve last year. If the pre-election week is any guide, it is evident that President Erdogan’s appetite to intervene in monetary policy remains unrelenting. The central bank suspended funding from the key one-week repo rate (introduced only last year), effectively hiking rates by 150 bps to 25.5% to stabilise the lira. Moreover, the TCMB also applied highly unorthodox measures of liquidity withdrawal to prevent lira short-selling on the money market. With the election over, the risk now is a premature start of an easing cycle before inflation rates begin a downward trend, which we expect no sooner than in summer 2019 (due to the base effect).

Secondly, the government’s fiscal policy also suffers from a significant credibility gap. Economic growth was to a large extent fuelled by cheap credit, underpinned by the Treasury-backed Credit Guarantee Programme for non-financial corporations (amounting to 285 bn lira, approx. 8% of GDP). Even less conventional measures include those aimed at curbing inflation, such as a state-mandated 10% discount on goods and services or government vegetable and fruit stalls. Therefore, the latest promises of major free-market economic reforms would represent a U-turn that would be, albeit desirable, surprising if delivered fully. A more likely scenario is the adoption of minor reforms which risks that rebuilding credibility will remain elusive.

...geopolitical risks remain elevated

Last but not least, the future path of Turkey’s economic development will also be determined by its ability to improve relations with the west, and in particular with the US. The liberation of Pastor Branson confirms this as it marked a period of warmer relations resulting in reduced market uncertainty. Still, there have been several pending issues which risk another standoff, e.g. the purchase of Russian military hardware (anti-missile systems S-400), disputes about intervention in Syria or Turkey’s lack of support for sanctions-led pressure on Iran. Nonetheless, the recent compromises promise further room for improvement in foreign relations in the coming four-year long election-free period. This alone, however, would hardly be enough to revive the Turkish economy.