More inflation in the eurozone? Germany holds the key

Read the publication below or click here to open the PDF

Recent economic indicators are not very encouraging for those hoping that inflation in the euro area will soon return to the ECB's 2% target. Economic growth decelerated sharply in 2018 and the previous acceleration in inflation was completely reversed in the final months of the year. Core inflation has not yet picked up, although stronger wage increases would have justified hopes of such a development. However, the slowdown in consumer demand growth has probably prompted entrepreneurs to reduce their profit margins rather than increase prices.

Low inflation in the eurozone also reflects the adjustment process whereby peripheral euro area countries continue to make up for competitiveness losses that occurred before the euro debt crisis. This is still not complete and implies that their inflation rates should remain below that of Germany. Consequently, as long as German inflation remains below 2%, average eurozone inflation cannot really get close to 2%.

A stronger stimulation of the German economy, and in particular of German consumption, could accelerate the process by stimulating German inflation. But such a stimulus is unlikely. A significant acceleration of German inflation to above 2% is therefore also unlikely. As other large euro area countries will have to keep their inflation levels below German levels for a long time to come in order to restore their competitiveness, a return to average inflation in the euro area close to the ECB's 2% target is likely to be a very long-term effort.

Disappointing inflation performance

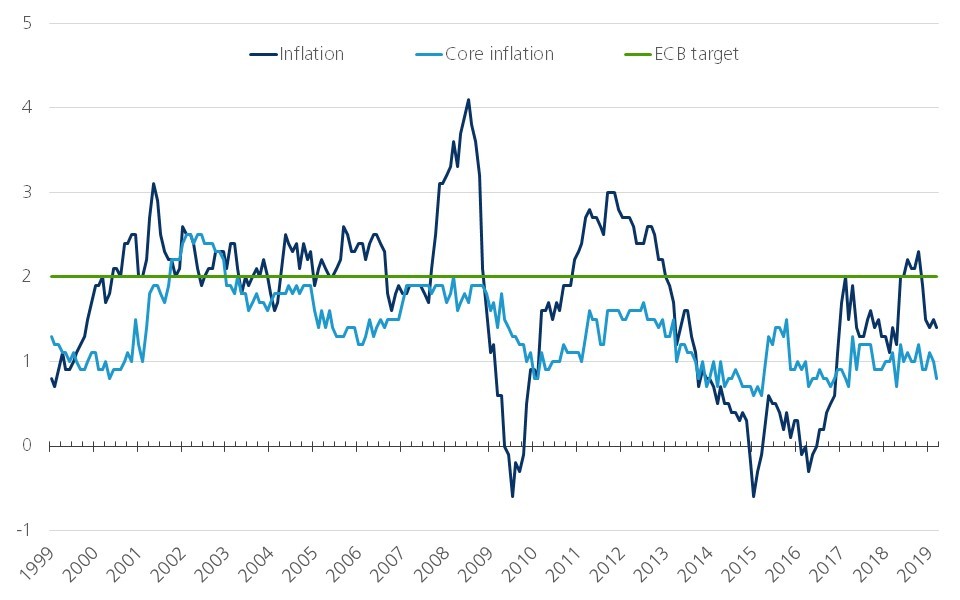

Inflation in the euro area has been disappointing in recent years, at least in light of the European Central Bank's (ECB's) objective. In the medium term, the ECB's objective is to achieve an inflation rate of less than, but close to, 2%. Between the launch of the euro in 1999 and the outbreak of the financial crisis in 2007-2008, this objective was achieved quite well, at least at first sight (see below). Over that time, inflation averaged 2% a year. However, since the 2011 euro debt crisis, it has not been possible to keep inflation permanently close to the target (Figure 1). Inflation fell from 3% at the end of 2011 to -0.6% in January 2015. It remained around 0% until mid-2016, after which it bounced back to 2% over the next half a year. Over the past two years, it has fluctuated between 1 and 2%.

Figure 1 - Inflation and core inflation in the euro area (annual change of the harmonised consumer price index, in %)

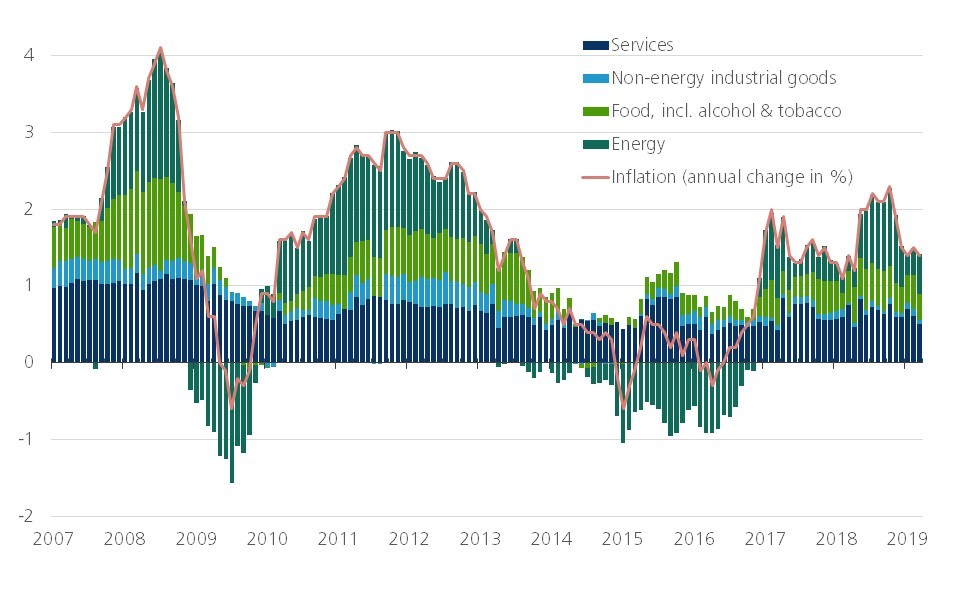

Since 2008, inflation has been strongly influenced by fluctuations in the consumer prices of energy products (Figure 2). These are very dependent on the whims of crude oil prices. The traditionally volatile prices of food, alcohol and tobacco also made their contributions. Episodes in the recent past during which inflation came close to 2%, were mainly the result of volatility in the price of oil and other raw materials. These prices are determined on international markets and say little about internal inflation dynamics. These volatile components, which make up 30% of the eurozone's harmonised consumer price index, rather obscure the picture of real inflation dynamics in an economy. They therefore are not included in core inflation. This measure rather looks at the evolution of the prices of non-energy industrial consumer goods and of services. The price of services (44% of the consumer price index in the euro zone) is mainly determined by domestic factors, such as labour costs.

Figure 2 - Drivers of inflation in the euro area (contribution to the annual change of the harmonised consumer price index, in percentage points)

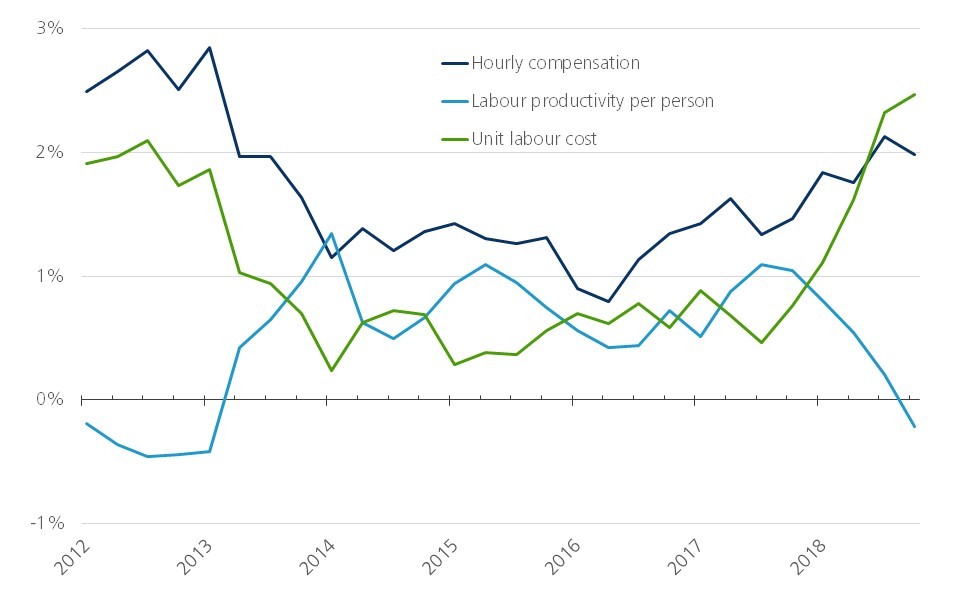

Core inflation in the eurozone has been fluctuating closely around an average of 0.9% since mid-2013. This level is only half of the average for the period 2001-2008. It has hardly accelerated during the recent boom period. In the first quarter of 2019, core inflation was still only 1%. This is disappointing, as economic growth has increased capacity utilisation in the economy surprisingly quickly in recent years. The labour market, in particular, increasingly showed signs of further tightness. As could have been expected, this has led to an increase in the rate of wage growth (Figure 3). Many economists expected this to gradually accelerate core inflation. After all, wage costs are by far the most important cost component in most sectors. If wages start to rise, this encourages entrepreneurs to raise their prices. But so far, this has hardly happened.

Figure 3 - Hourly wages, labour productivity and unit labour costs in the euro area (annual change in %)

Inflation and economic slowdown:

an ambiguous relationship

The fact that entrepreneurs have not passed on the increase in labour costs to consumer prices may be due to the significant slowdown in the economy over the course of 2018. In principle, a slowdown in the economy has an ambiguous impact on the passing on of costs. On the one hand, it increases cost pressure. Indeed, a weakening of the economic climate is accompanied by a weakening of the turnover of companies. If wage increases are no longer financed by higher sales revenues, this will affect company profitability and productivity. Entrepreneurs will want to avoid this by raising their prices. In this way, a slowdown in the economy would encourage the acceleration of inflation.

But a slowdown in the economy also means that demand is weaker. This reduces the price-setting power of entrepreneurs. Price increases in the face of weakening demand are particularly likely to increase the stock of unsold goods. This also affects company profitability. Business leaders will therefore have to consider which of the two options will do the least harm.

Apparently, in the past year they have mainly chosen to reduce their profit margins. As might have been expected, the economic slowdown in the euro area in recent quarters has slowed productivity growth (Figure 3). This has increased the pressure on costs due to accelerating wage increases. However, as consumption demand slowed down (Figure 4), these cost increases were not passed on to consumers. They were cushioned by a narrowing of profit margins, which had, moreover, previously evolved to a fairly high level.

Figure 4 - Consumption expenditure of households (in volume, annual change in %)

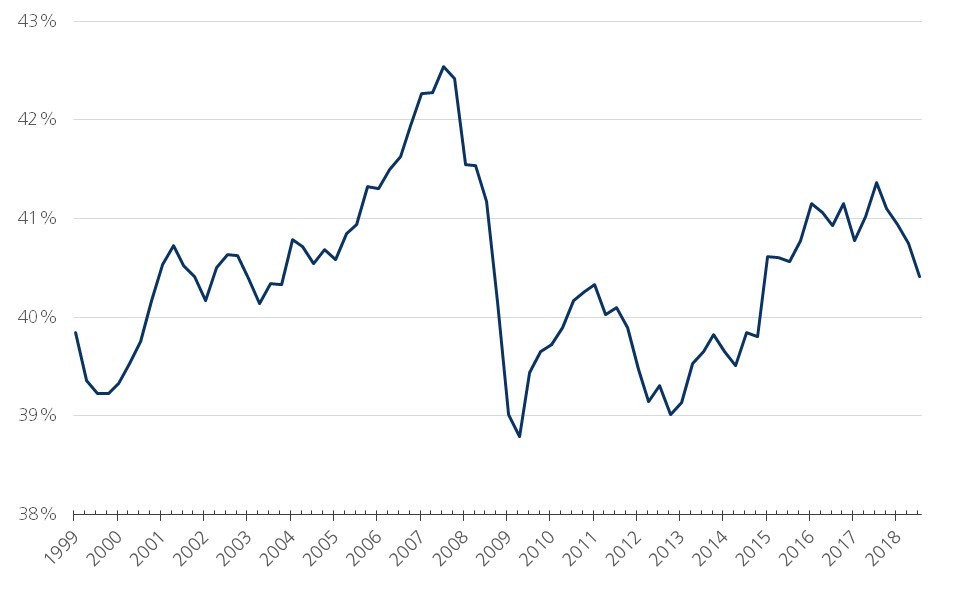

Figure 5 illustrates this with the macroeconomic accounts of non-financial enterprises for the euro area as a whole. The downward pressure on operational profitability is, however, more or less noticeable in all major euro area countries. The evolution of the profits of the main listed companies in the euro area also points in the same direction. According to the I/B/E/S data, their profit growth has fallen from over 10% in 2017 to less than 2% in 2018. Due to shrinking margins, inflation did not accelerate.

Figure 5 - Profit margin of non-financial corporates in the euro area (operating surplus and mixed income as a % of gross value added)

Disinflation, typical eurozone...

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, low inflation was a global phenomenon. It was associated with globalisation, which dampened inflation through increased competition in product and labour markets. Until 2013, core inflation in the euro area was broadly in line with developments in other OECD countries (Figure 6). Since then, however, there has been a decoupling. After a gradual increase in core inflation in 2013-2017, the OECD experienced a marked acceleration in inflation in 2018 - in line with what could be expected in the wake of the global boom. In contrast, core inflation in the euro area continued to decline in 2013-2014, followed by a long period of stabilisation. Recent studies by the ECB (2017) and the IMF (2018) suggest that this disinflation was mainly due to domestic factors.

Figure 6 - Core inflation: euro area versus OECD (annual change of consumer price index, excl. food and energy, in %)

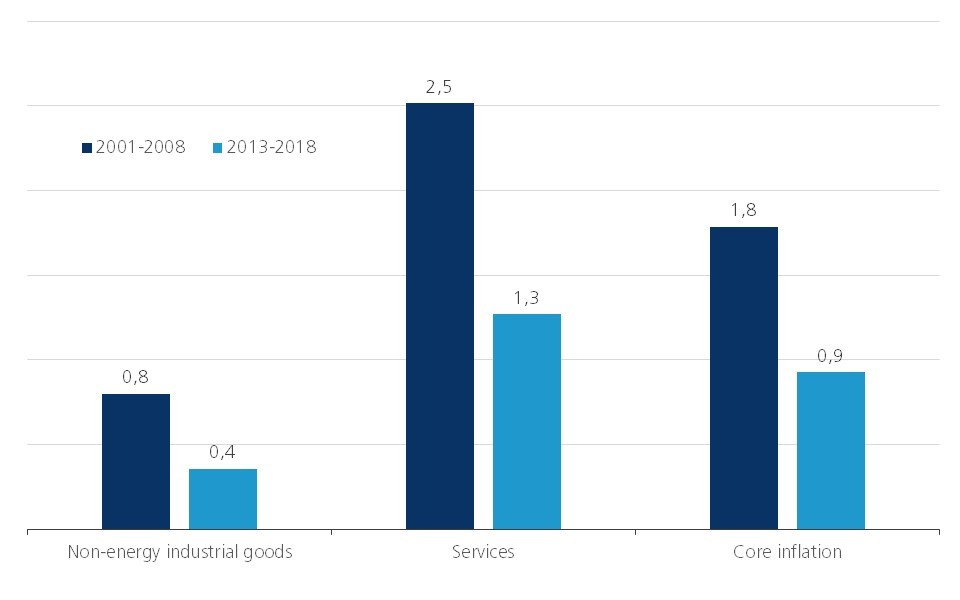

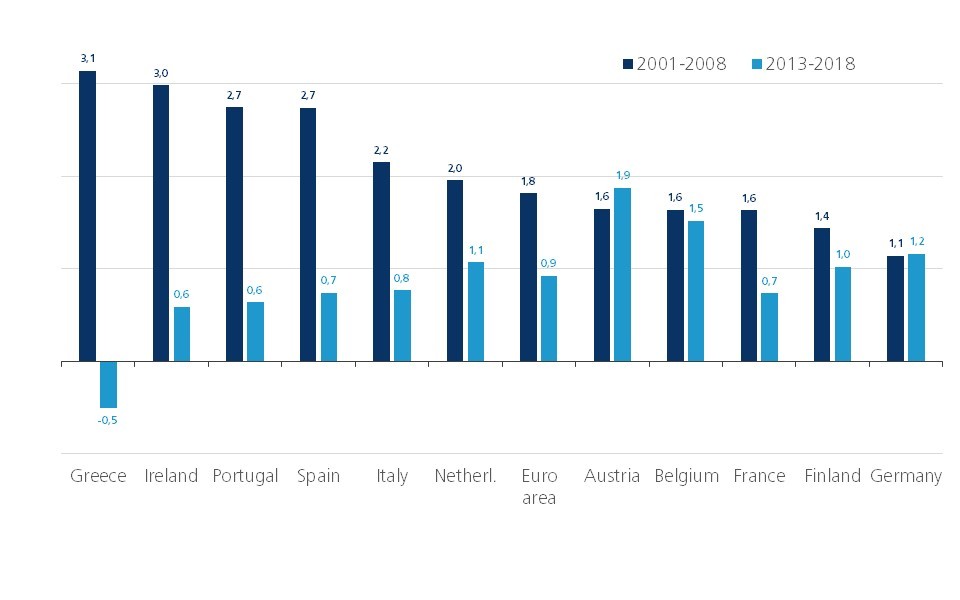

Figure 7 illustrates that the halving of core inflation compared to the pre-crisis period is due to the cooling of both non-energy industrial goods and service inflation. Disinflation occurred in all subsectors of both the services and consumer goods industries. This development can be found in almost all euro countries. Only in Austria, Lithuania and Germany was average core inflation slightly higher in 2013-2018 than in 2001-2008 (Figure 8).

Figure 7 - Core inflation and its main components in the euro area (yearly avg of annual change of the harmonised consumer price index, in %)

Figure 8 - Core inflation in the main euro area countries (yearly avg of the annual change of the harmonised consumer price index, in %)

... but especially in the peripheral countries

On closer inspection, however, Figure 8 shows two more things. Firstly, disinflation is generally significantly stronger in the countries most affected by the euro crisis (Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Italy). The Dutch economy also continued to experience relatively severe weather during the euro crisis, resulting in strong disinflation. These are also the countries in which inflation in the period prior to the crisis was often significantly higher than the average for the eurozone. As noted above, average inflation in the eurozone in the pre-crisis period was close to the ECB's target of 2%. However, here it is shown that it was the result of a significant overshooting of the target in the peripheral countries and lower inflation in the core countries, particularly in Germany.

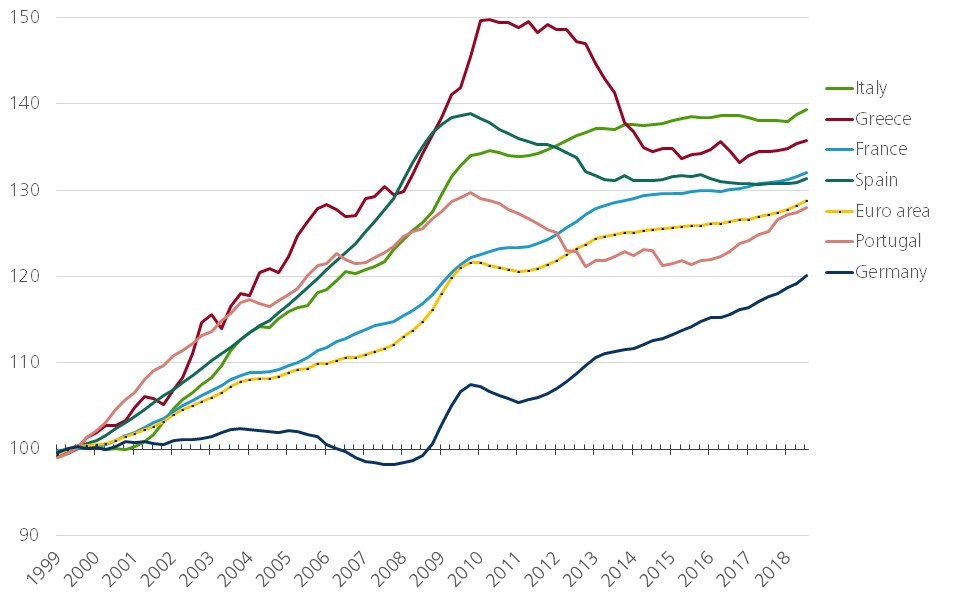

Higher inflation in the peripheral countries reflected the sharp rise in unit labour costs (Figure 9), which in turn led to a loss of competitiveness. In recent years, these countries have had to regain said lost competitiveness. Wage moderation and structural economic reforms are then the order of the day. In all probability, these factors are partly at the root of the strong disinflation in these countries. Wage moderation dampens cost pressures and structural reforms often aim to increase competition in the market. This makes it more difficult to raise prices.

Figure 9 - Nominal unit labour cost (selected euro area countries; index, 1999 = 100)

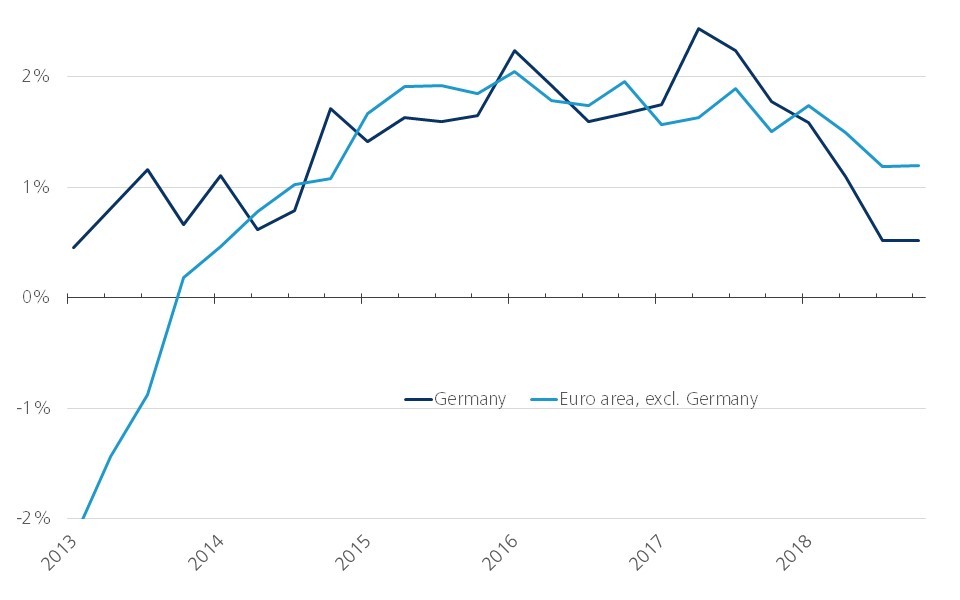

The key is in German hands

The second striking observation in Figure 8 is that German core inflation in 2013-2018 was barely higher than in 2001-2008, averaging 1.2% per year against 1.1%. Despite a slight acceleration, it has still only been around 1.5% in recent months. In Germany too, the expectation that the acceleration of wage growth (see below) would fuel inflation is only slowly being met. This may seem surprising against the background of the historically low German unemployment rate, but it is less surprising in light of the slowdown in economic growth. This is not only due to the trade war between the US and China and the deterioration in the international trade climate, which is hampering German exports. It also reflects a significant slowdown in the growth of household spending in Germany. Household spending fell from 2.5% (annual increase in volume) at the beginning of 2017 to barely 0.5% in the second half of 2018 (Figure 4). This is a more pronounced slowdown than in the other euro countries. It is likely to throw a spanner in the works for managers who want to raise their prices.

Both observations are important with a view to estimating the future rate of inflation in the euro area. Figure 9 suggests that wage competitiveness within the euro area has not yet fully recovered. Taking 1999, the year of the introduction of the euro, as a starting point, Germany still has a labour cost advantage over all the euro countries shown, ranging from 7% (versus Portugal) to 16% (versus Italy). This is despite the significantly higher German wage cost increase in the post-crisis period (on average 1.8% per year in 2012-2018) than in the pre-crisis period (on average 0.5% per year in 1999-2009).

Countries that want to eliminate a competitive handicap compared to Germany, need to make peace with an inflation rate below that of Germany. In order to reach an average inflation rate of 2% in the euro area, German inflation would therefore have to be temporarily well above 2%. In other words it needs to be significantly above its current level. In this way, Germany holds the key to higher inflation in the euro area.

However, recent economic developments suggest that the door will not open soon. In December 2018, the Bundesbank's economic outlook included a forecast that German core inflation would not rise to 2% until 2021. In the meantime, the outlook has deteriorated. In its latest forecasts (March 2019), the German Council of Economic Experts forecasted real GDP growth of only 0.8% in 2019. This is less than half of the growth forecast of the Bundesbank last December. Separately, the federal government has just halved its own growth forecast for 2019 to barely 0.5%.

In the coming months, the temporary factors that contributed to the recent downturn in German growth will fade away. This will allow for a slight rebound in growth, but a strong recovery is unlikely. Stimulus from abroad is unlikely in the short term and, despite employment growth and rising wages, domestic consumption demand is lethargic. The easing of German fiscal policy will bring some, but probably not much, relief. It is remarkable how German households are currently pushing their savings ratios to historic highs.

Germany could open the door to higher inflation more quickly and widely by loosening its fiscal policy more than currently foreseen in the 2019 budget. According to preliminary estimates (Bundesbank, 2019), the general government surplus increased further to 1.7% of GDP in 2018. Public debt is falling at a rapid pace. In this respect, there is plenty of budgetary room for stimulus. Moreover, the huge current account surplus of the German balance of payments points to a large lack of domestic spending. This is an imbalance which, according to the EU's economic policy commitments, should be corrected as a matter of urgency. However, there is little political appetite in Germany for a further relaxation of fiscal policy. On 20 March, the federal government approved the broad outlines of its multi-annual budget up to 2023. The continuation of a balanced budget or Schwarze Null was an absolute precondition for this.

From an economic point of view, the argument in favour of budget stimulus is also ambiguous. In order to boost inflation in the short term and eliminate the external surplus, Germany should above all stimulate consumption. However, the German economy also needs to strengthen its growth potential in the longer term, partly in view of the demographic ageing of the population. This requires, in particular, an increase in investment. Stronger investment would make little contribution to a sustained increase in inflation.

Conclusion

A significant acceleration of German inflation to above 2% is therefore unlikely to take place. As other large euro area countries will have to keep their inflation levels below German levels for a long time to come in order to regain their competitiveness, a return to average inflation in the euro area close to the ECB's 2% target is likely to be a very long-term process.